Early Findings: Review of State and Local Government Ransomware Attacks

Click here to download the complete analysis, including all of the data referenced in this piece, as a PDF.

Author’s Note: The cutoff for this report was the end of April, 2019. Since then, there have been at least three new ransomware attacks against state and local governments: Lynn, Massachusetts, and Cartersville, Georgia, as well as Baltimore, Maryland, which was hit for at least a second time. Unfortunately, ransomware attacks against state and local governments are not going away anytime soon.

2019 marks the 30-year anniversary of the first ransomware attack. PC Cyborg (also known as the AIDS Trojan because it targeted AIDS researchers) was clunky and required mailing a physical check to an address in Panama. However, modern ransomware — the kind that most people think of today with Bitcoin demands and threats to have all your files deleted — started in 2013 with ransomware variants like CryptoLocker.

State and local governments were among the first organizations to be hit with ransomware. The first known case was in November 2013, when the Swansea Police Department in Massachusetts was infected with CryptoLocker. There may have been more infections, but ransomware was not a commonly used term in 2013 (see the Kaspersky definition of CryptoLocker as a “virus”), and any earlier attacks may not have been reported as such.

Since then, there has been a lot of discussion around ransomware attacks targeting state and local governments, and the attacks have seemingly continued to grow over the years. But I wanted to understand the nature of these attacks and determine whether ransomware is really on the rise in the state and local government sector. To that end, building on the excellent research done by the team at SecuLore through the Recorded Future data set, and searching through local news sources, I was able to catalog 169 ransomware incidents affecting state and local governments since 2013. This report is a discussion of the findings and trends.

It should be noted that this list should not be viewed as exhaustive. Ransomware attacks are not always publicly reported by state and local governments and there is no centralized reporting authority, similar to HIPAA requirements, for these agencies. This means that the number of incidents is most likely underreported. Some ransomware incidents may also be simply reported as a malware attack rather than specifically as a ransomware attack. These incidents would not have been cataloged in the search.

Before diving into the results, I do want to say that most of the incidents would not be widely known if not for the work of local journalists. A lot of the information I was able to find was in local papers or local television news reports, which makes sense — most of these incidents are not “big enough” to be considered national news, so local journalists would be the only ones covering them. Covering cybersecurity is not an easy task, never mind when your typical coverage tends to center on daily business news. We commend these journalists for taking on the effort and are grateful for the work they’re doing.

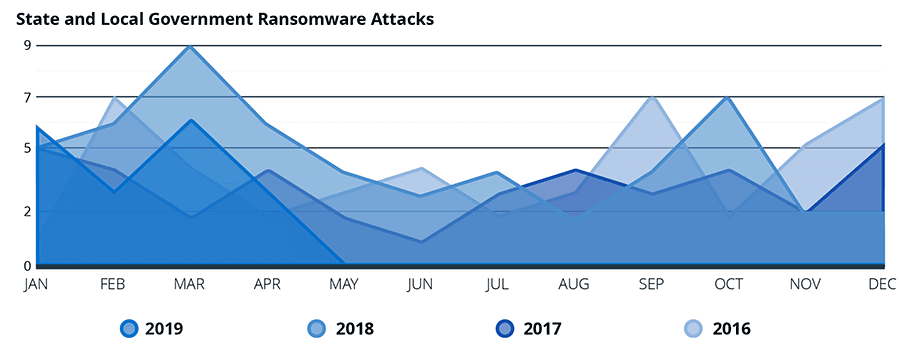

First, it does appear that ransomware attacks on state and local governments are on the rise. In 2016, I was able to find 46 ransomware attacks. In 2017, that number dropped to 38, which is reflective of a drop in ransomware attacks across all sectors. In 2018, that number jumped to 53, and in the first four months of 2019, there have already been 21 reported attacks. The numbers for 2018 and 2019 may go up, as not all ransomware attacks against state and local governments are reported immediately. Many of the attacks in the catalog were reported weeks or months after they happened, often during city council or budget meetings.

The second finding is that, despite the use of the word “targeted,” it does not appear that these are targeted attacks in the traditional sense. These attacks tend to be more targets of opportunity. Even groups like the teams behind Ryuk and SamSam appear to stumble into these targets. However, once these groups do realize they are in a state or local government target, they take advantage of the fact by targeting the most sensitive or valuable data to encrypt.

A third, and possibly surprising, finding is that state and local governments are less likely than other sectors to pay the ransom. According to a 2019 report from CyberEdge, 45 percent of organizations that were hit with ransomware paid the ransom (this number is up from 38.7 percent in 2018). Based on our analysis, only 17.1 percent of state and local government entities that were hit definitely paid the ransom, and 70.4 percent of agencies confirmed that they did not pay the ransom.

Due to limited data availability, I was not able to determine things like which ransomware variants are most often used in these attacks or get a good grasp on the total amounts of ransom demanded.

That being said, I was able to find ransomware attacks that hit 48 states and the District of Columbia. The states with no publicly reported ransomware attacks are Delaware and Kentucky. Note that this does not mean no ransomware attacks occurred, just that they were not publicly reported. For example, this write-up of a recent attack against Garfield County in Utah mentions that “… the FBI is aware of other ransomware attacks on other Utah governments,” but I was unable to find other publicly reported attacks against Utah government agencies. This may be an indication that state and local government ransomware attacks are underreported.

24 of the 169 attacks were against local school systems or colleges. Again, these attacks do not appear to be targeted — it was more a matter of opportunity. 41 of the attacks were against law enforcement offices, though there is some overlap because several attacks that started with local government computers would spread to law enforcement systems as well.

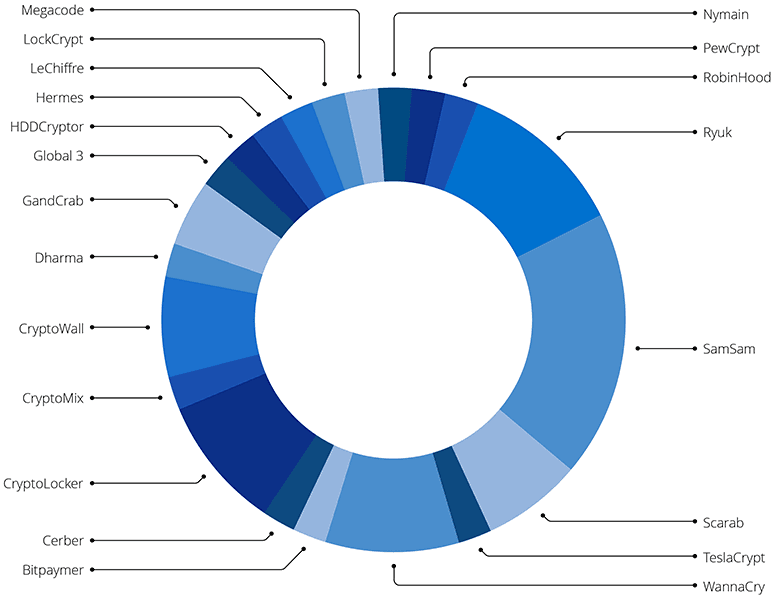

A breakdown of the known types of ransomware used in the attacks. This does not include the category of unidentified pieces of malware, which comprise 76 percent of the total.

Reporting on the type of variant used in these attacks is limited. Only 40 of the 169 reported incidents identified the type of ransomware used in the attack. The variants used in these attacks do seem to mirror the ransomware families used against other sectors. From 2013 to 2016, the primary families reported were CryptoLocker and CryptoWall. In 2017 and 2018, that transitioned to WannaCry and SamSam (though the WannaCry attacks were, unsurprisingly, mostly closely clustered together in May and June of 2017). More recently, in late 2018 and early 2019, the primary ransomware families have been GandCrab and Ryuk.

Overall, ransomware attacks on state and local government agencies are a growing problem. The trend for state and local governments follows an interesting pattern. There was a surge of attacks in 2016, but the number of attacks decreased in 2017. This mirrors ransomware attacks overall for 2016 and 2017. What is interesting is that while 2018 saw a small resurgence in overall ransomware attacks, there was a sharp jump in ransomware attacks against state and local governments, and that surge seems to be continuing into 2019.

Although state and local governments do not pay ransoms nearly as frequently as other targets, they generate outsized media coverage because of the effect these attacks have on the functioning of essential infrastructure and processes. This likely creates a perception among attackers that these are potentially profitable targets. The data shows that the reality is more of a mixed bag — although government agencies are less likely to pay the ransom than other victims, there is still an almost one in five chance that an attacker will get paid. Further, these targets may raise the profile of the attacker (for better or worse) since these agencies are more likely to call in law enforcement and the FBI to assist with the ensuing investigations.

Related