Shell No! Adversary Web Shell Trends and Mitigations (Part 1)

Analysis Summary

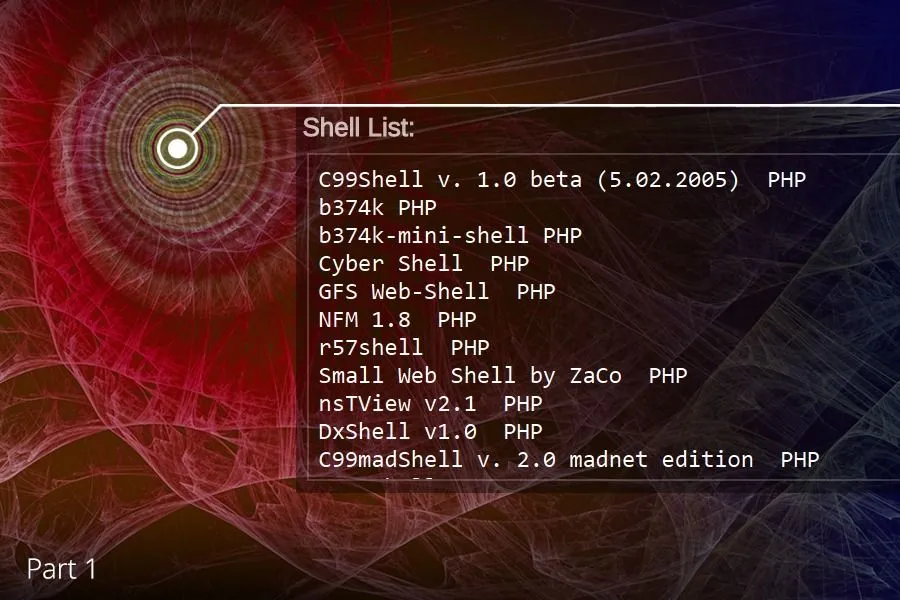

- Open sourcing unauthorized persistence with web shells for over 15 years.

- Web shells are a favorite Chinese speaking forum topic.

- Actor laziness leads to code reuse, but not enough to alert on functions or strings.

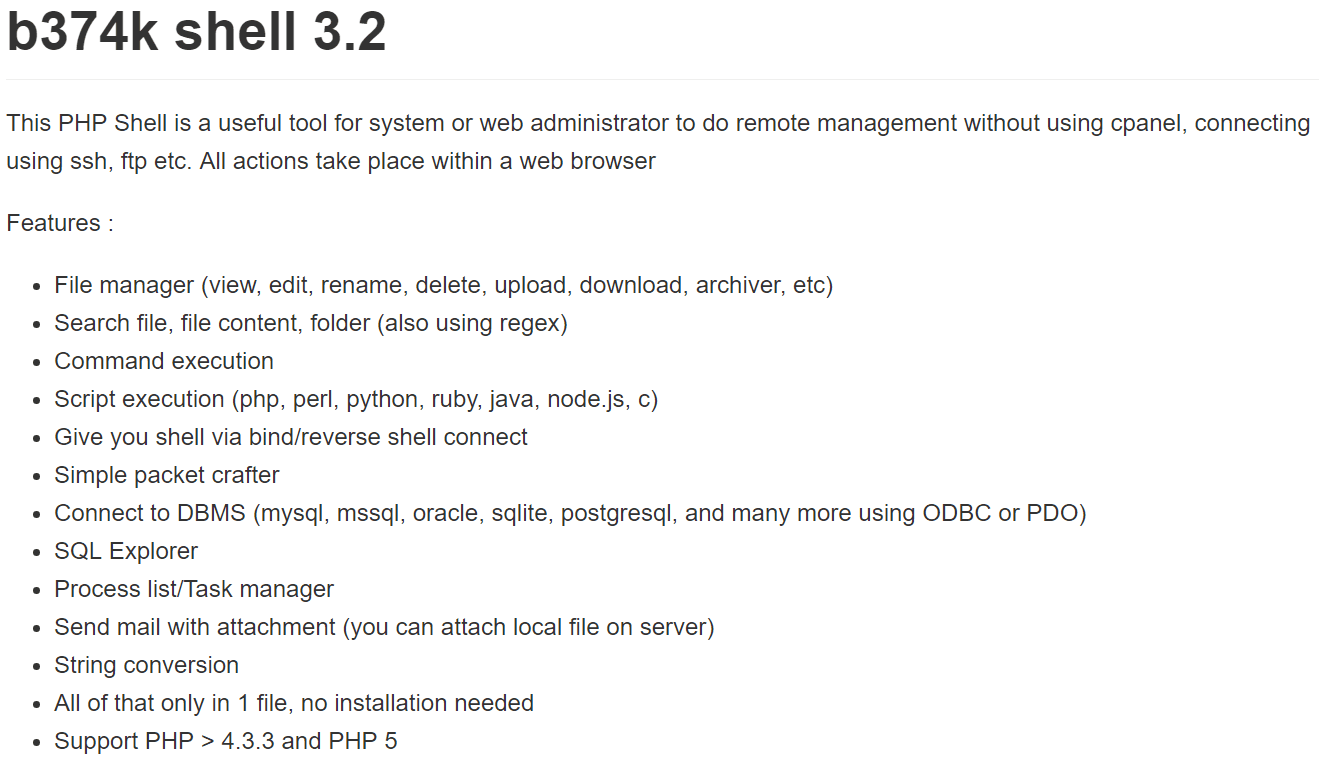

- b374k, b374k r3c0d3d, and WSO 2.1 are clear open source favorites (by mention).

- Static signatures that capture specificity or uniqueness in a web shell are only marginally useful. Higher-level web shell behaviors are the choke points to focus on for long-term, large-scale meaningful detection.

Incident responders have been dealing with web shells since the dawn of the web and adversary options continue to grow.

Spear phishing and drive-by/watering hole attacks may be top of mind for defenders, but web application vulnerabilities and the resulting web shell placements are an attractive “first option” mechanism for maintaining a foothold in a victim network while pursuing deeper access and data.

We present the following web shell primer and highlight recent underground economy developments in part one of this two-part series.

Background

A web shell is code that is interpreted and run by an HTTP server daemon (a “web server”) and is designed to provide a graphical interface for remote access to the server, it’s file system, and often the underlying operating system.

Web servers running Microsoft’s IIS on Windows are typically targeted by Active Server Page (ASP) code, while Apache and/or Nginx running on Linux/*BSD are often the recipients of PHP or Perl code. Web shells are created in many different languages (Java, Python, etc.), the only requirement is that the intended server must be able to natively execute the code instructions.

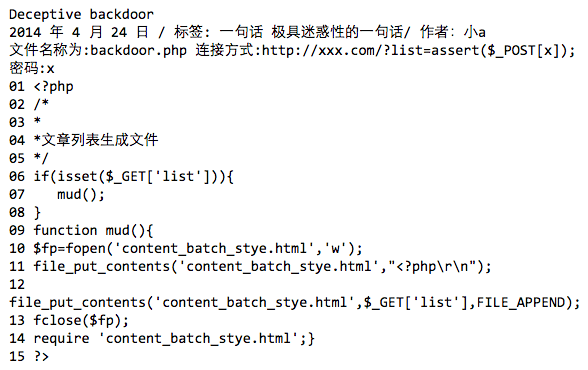

15 lines of PHP to write to a file and maintain access.

When web shell code is invoked by a remote user calling the file (typically in a web browser), a control panel (of sorts) is presented. Web shells aren’t inherently malicious, but few system administrators choose to create a web interface for remote management. Thus most web shell code is created and maintained by adversaries. The term “shell” obviously implies Unix style command line access delivered via the web server.

Defense vigilance with one web server or even a couple of web servers is achievable, but when enterprises run hundreds of web servers, with different operating systems, applications, and local users constantly adding and editing files, the ever-changing complexity makes malicious web shell detection extremely difficult.

Bill Powell of Payment Software Company frequently encounters web shells on victim servers during incident forensics and investigations work. Bill says, “… of the samples I have recovered, between 20% and 25% were detected by anti-virus/anti-malware solutions. If in a single given system, I may find one or two articles of malware (non-web shell malware), the least amount of web shells I have found on a system has been eleven, with the most being almost thirty on a single system in a single environment.” Clearly businesses should be concerned about their web shell detection strategy.

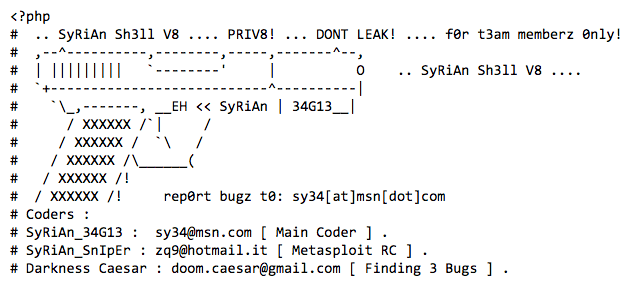

Comments from the Syrian Shell.

Web shells don’t magically appear on servers.

Rather, adversaries must identify an exploitable vulnerability first. The OWASP top ten vulnerabilities are a good starting point, such as looking for SQL injection (SQLi) opportunities or PHP remote file include (RFI) input validation failures. More advanced tactics include finding new vulnerabilities in content management systems (CMS) such as Joomla, Drupal, and WordPress, as well as the hundreds of respective plugins.

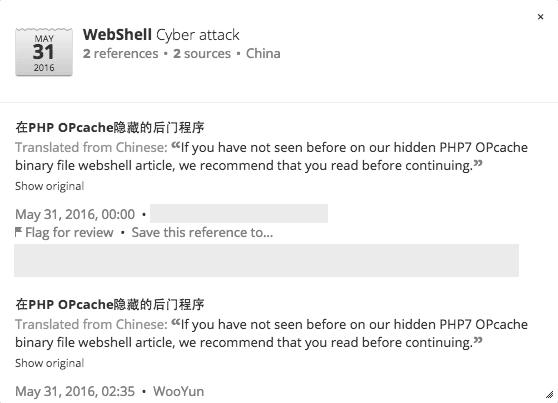

Often PHP itself is the source of frustration as evidenced by the recent announcement of an exploit methodology using PHP7’s new OPcache functionality.

Ultimately, the bar is relatively low, as adversaries must only be able to upload their web shell file to a writeable directory or modify an existing file on a web server.

Chinese speaking forums discuss the latest PHP7 vulnerability.

In 2016 even the most technically challenged adversaries can locate vulnerable web servers in minutes through open source information and dorking. Criminal forums facilitate best practice sharing so it’s only a matter of time before vulnerable public facing web servers are located and exploited.

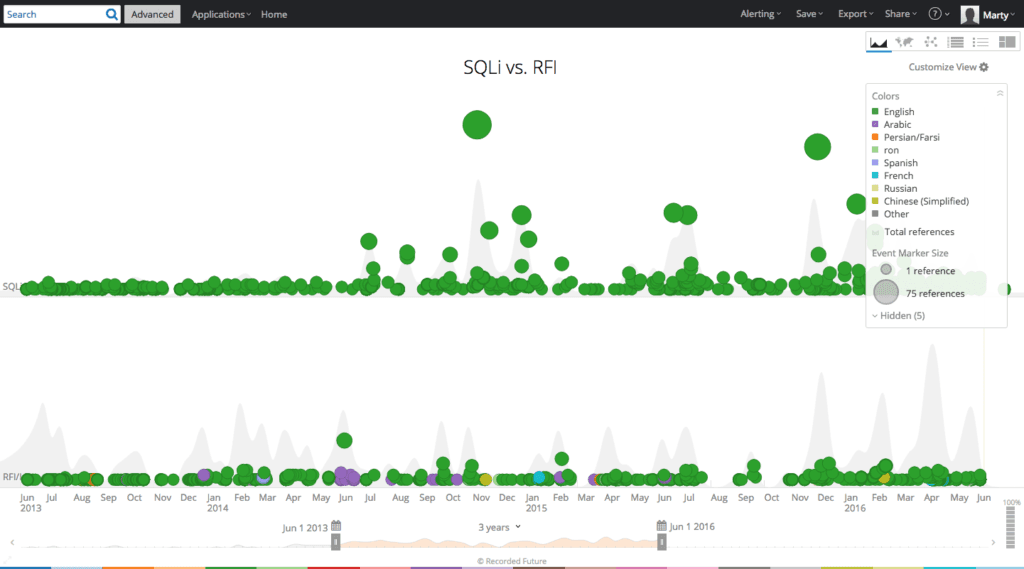

A three-year comparison of SQLi and RFI references on the web categorized by language in Recorded Future.

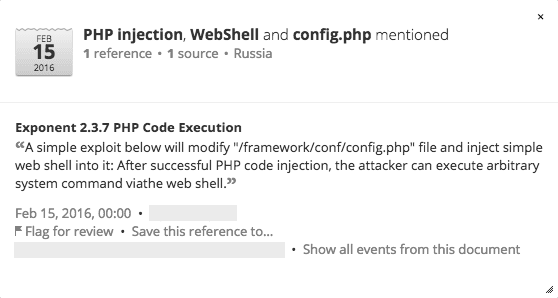

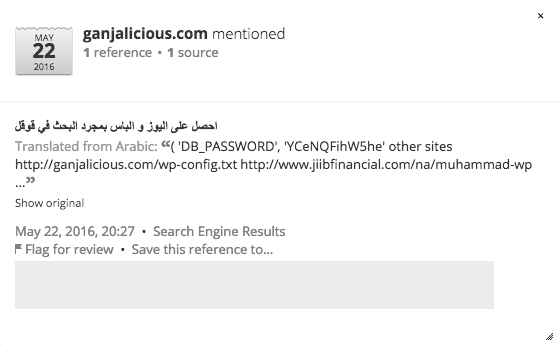

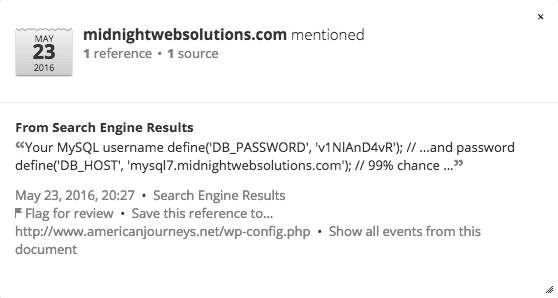

Dorking results for vulnerable web servers displayed in Recorded Future.

Displaying dorking results in Recorded Future.

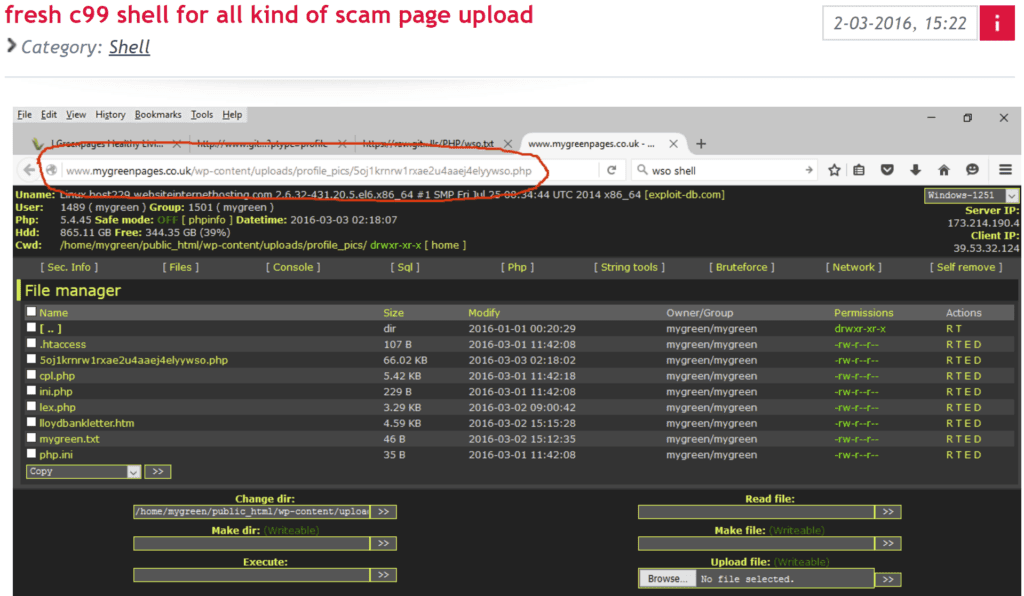

Once victim web server unauthorized access is complete, the actor adds code to an existing file on the server and/or uploads a new file containing the web shell code. The example C99 web shell screen shot below displays typical user options/capabilities once the actor navigates to the newly created PHP file on the target web server.

An actor advertises a C99 shell for use in phishing campaigns and/or other fraud schemes.

Once the web shell is accessible, the actor can use it for an array of malicious activities including a few of the following:

- Searching for credentials

- Elevating privileges

- Identifying additional resources on the target network

- Locating databases and exfiltrating data

- Denial of service

- Redirecting website visitors to a watering hole/drive-by campaign

- Installing a proxy for future anonymization

- Long-term persistence on the server

The web server becomes a valuable resource to accomplish nation state goals and/or more pedestrian criminal monetization.

Trends

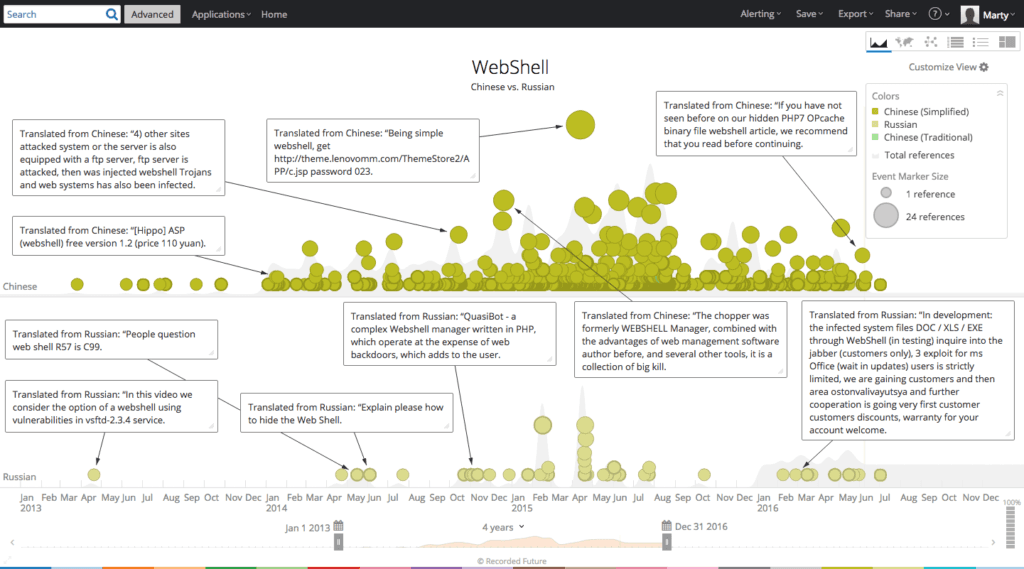

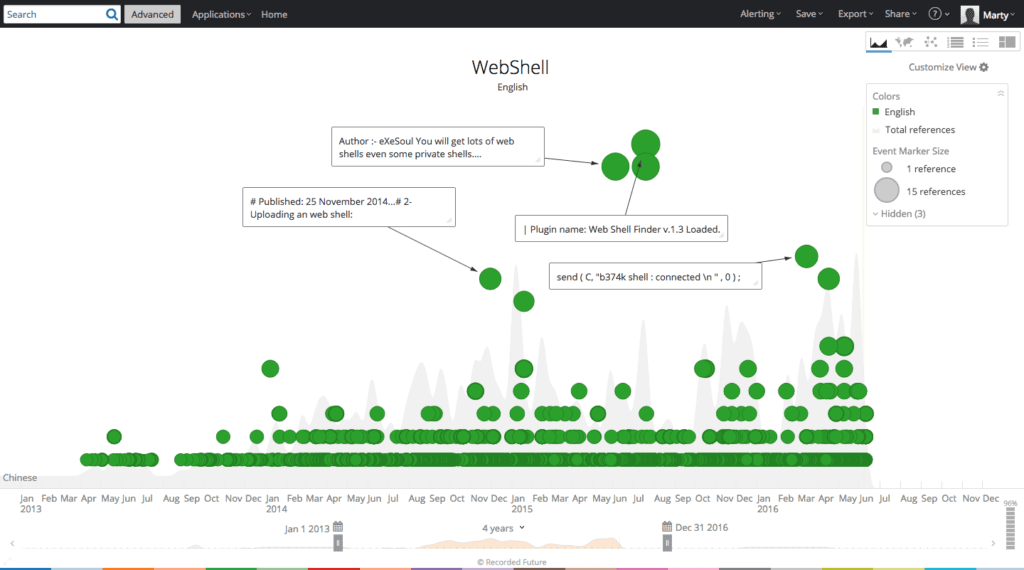

A three-year review of web shell entities (an entity in Recorded Future is a text reference that is recognized via natural language processing, in this case, as a malware component) in forums, paste sites, and code repositories by language reveals that English and Chinese are the most prolific languages for web shell mentions.

While the quantity of web sources in each language differs, and disregarding normalization, it’s still clear that English and Chinese speaking individuals are most actively mentioning web shells in the public web.

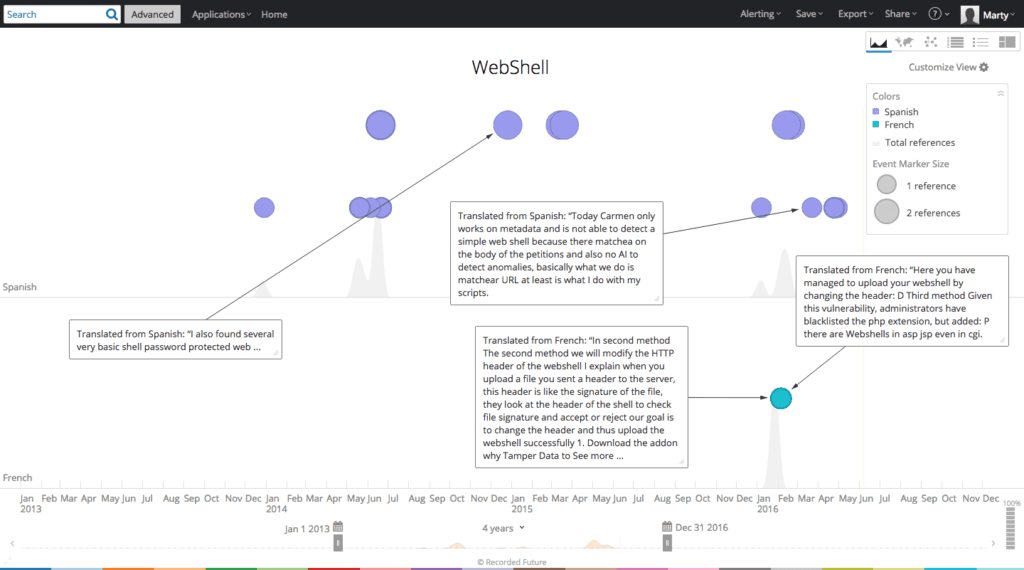

Web shell mentions — Spanish versus French.

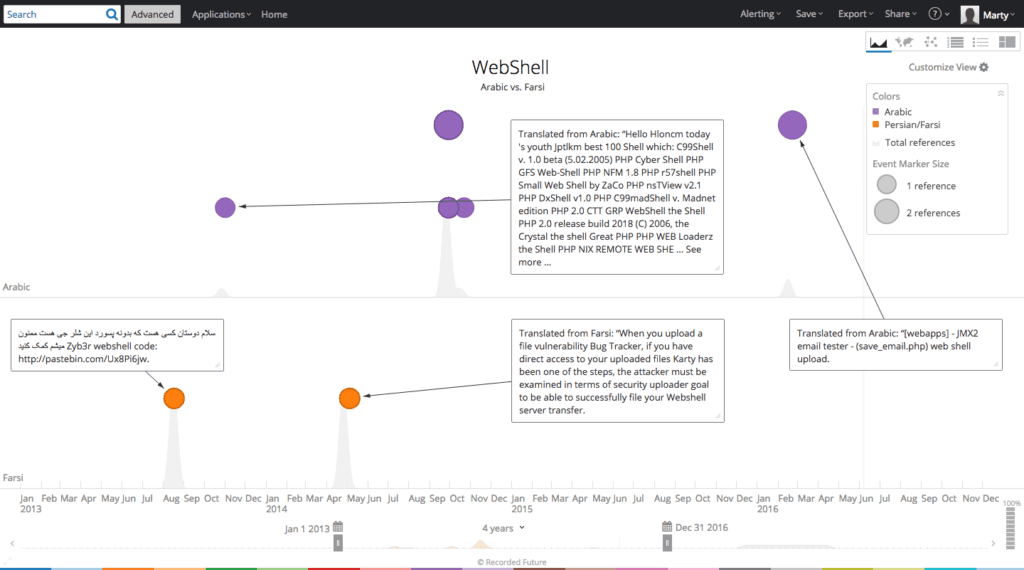

Web shell mentions – Arabic versus Farsi.

Web shell mentions – Chinese versus Russian.

Web shell mentions – English.

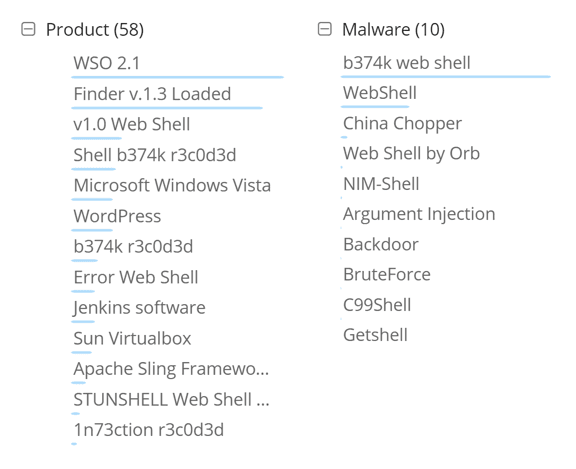

Looking at the automatic categorization and frequency of web shell family mentions in Recorded Future reveals b374k, b374k r3c0d3d, and WSO 2.1 are clear open source favorites.

Automatic categorization of web shells via natural language processing (NLP).

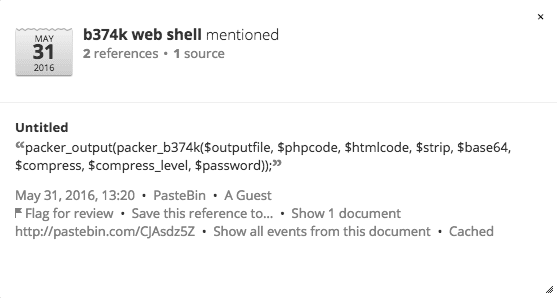

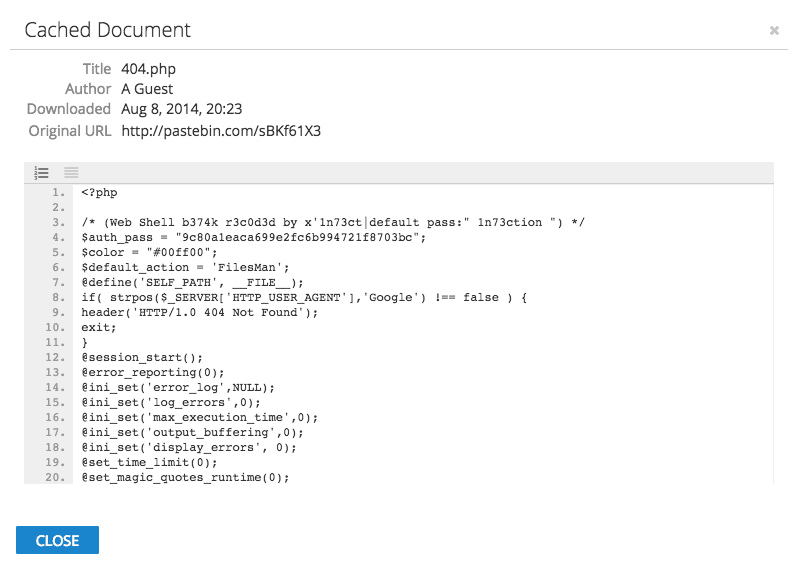

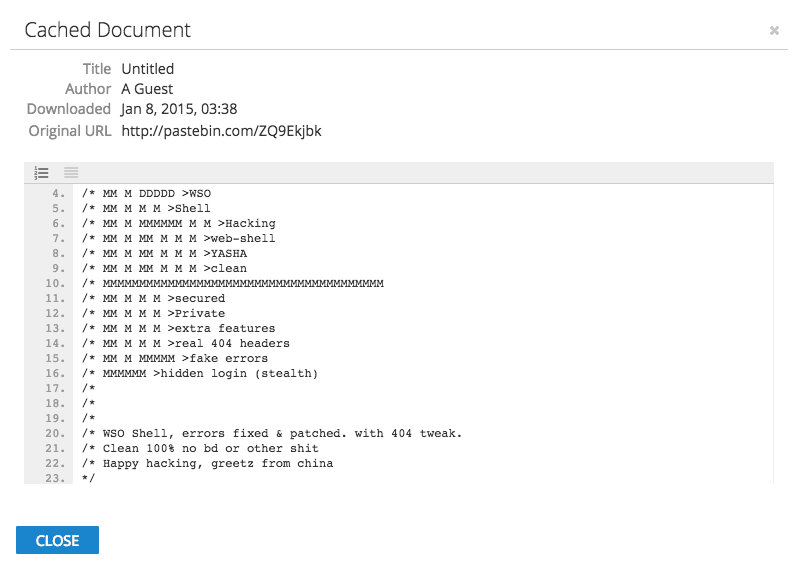

Digging into the results reveals web sources where actors are uploading web shells and open sourcing long-term development as seen below.

Alerting on web shell references in Recorded Future.

Web shell families differentiate themselves with features like hidden authentication, back connect, and deception — in the form of a HTTP 404 error page. If an individual arrives at the web shell without satisfying some conditional logic such as using the correct referrer page and/or user agent, web shell detection becomes more difficult, especially for an uninitiated system administrator.

Building “404 error page” functionality into the web shell.

Link: hxxp://nilsonlombardi.com.br/ing/fotos/shell.php

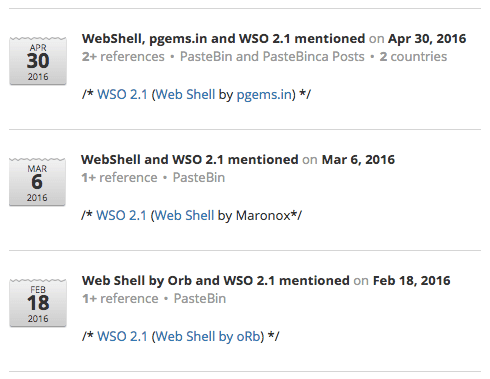

Web shell by orb (WSO) continues to be the most prolific open source web shell by mentions, primarily because variants are posted to paste sites weekly.

Recent WSO references in Recorded Future.

Sharing the WSO web shell.

Code Analysis

A common practice among web shell users is to obfuscate the shell file to make detection in transit and storage more difficult for operational defenders.

To think about worthwhile detection methodologies, we reviewed multiple open source web shell repositories for code commonality. The following repositories contain obfuscated and de-obfuscated web shells:

- https://github.com/BlackArch/webshells

- https://github.com/malwares/WebShell

- https://github.com/bartblaze/PHP-backdoors

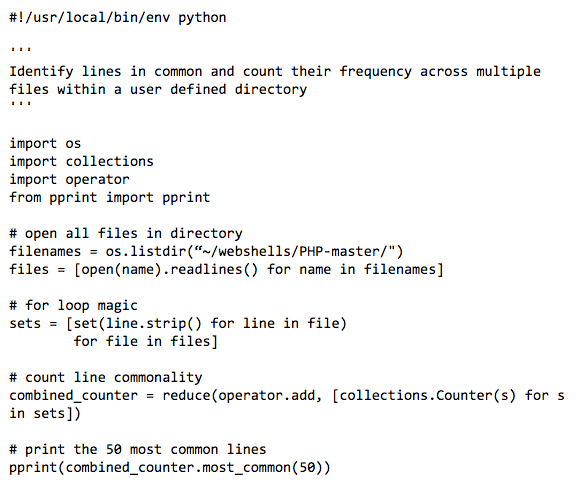

Aggregating the three repositories into one directory results in approximately 260 de-obfuscated PHP files, 99 obfuscated PHP files, and a combined 10 ASP, ASPX, JSP, and Perl files. The Python collections module is subsequently used to recursively compare relevant files in a specified directory.

The results for the directory containing obfuscated PHP files returns little of interest, as expected, other than the use of FOPO (Free Online PHP Obfuscator) by older web shell families. The below results list the text fragment in common followed by the frequency count (edited for brevity and relevance).

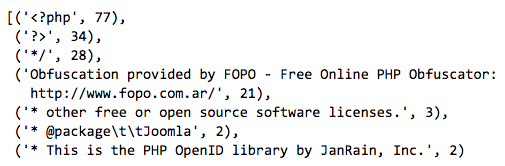

The Python script results for the un-obfuscated PHP files contain more commonality related to specific PHP functions, which could be useful for string based detection in some instances, but there’s nothing unique across all families. For example, the @set_magic_quotes_runtime function appears in only 18.5% of the samples and is removed in PHP7.

Regardless, all three of the below PHP functions could be used in legitimate PHP applications making detection unrealistic without a large amount of false positives.

Detection

Rogue web shell detection and prevention strategies are fairly straightforward when the self-administered network contains single digit webservers — generally found in small and medium-sized businesses. Security practitioners can manageably keep inventory of users, access permissions, and legitimate files/directories.

Additionally, it’s feasible to implement web server best practices on a consistent basis.

A Chinese language forum re-posting web server security advice from Sucuri.

The enterprise is a different story.

Often businesses are managing double-digit or even triple-digit web servers. The situation becomes more complex over time as additional web servers are introduced running heterogeneous operating systems, web daemons, application software like content management systems (Joomla, WordPress, Drupal, etc.), and historically vulnerable plugins.

Often there’s a lack of central responsibility for server administration let alone security. Access permissions aren’t necessarily tied to a central authentication mechanism like Active Directory and content owners are completely unaware of which files belong on the web server.

These types of environments allow web shells to remain undetected, often leading to multiple web shell placement by multiple adversaries on the same server.

The most important piece of any security prevention strategy is “know thyself,” and the motto is doubly important for web servers. Beyond self-discovery, a combination of host and network analysis methodologies will also help detection.

Specifically, security information and event management (SIEM) software can be used to analyze the usual suspects of HTTP user agent or referrer anomalies. Large scale file integrity monitoring can be implemented on web servers, but there are always limits to the strategy’s efficacy.

In enterprises, the scale of web servers and the amount of daily directory/file changes introduced by multiple administrators and content owners makes file integrity monitoring impractical. The network monitoring piece is difficult because HTTP traffic tends to exhibit a long tail of results for any specific search criteria leading to sub-optimal noise to signal ratios.

String-based web shell detection is impractical as a higher-level methodology, evidenced by the hundreds of Yara rules that address specificity and uniqueness in an individual file or family.

Attempting to alert on encoding and transposition functions is ineffective because there’s always a less obvious method of calling the functions that will evade detection.

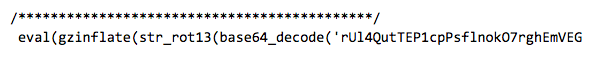

Consider a typical example of a web shell delivered as a string, which is subsequently evaluated by the web server, using the ubiquitous PHP “eval” function to execute the code after successfully decoding the Base64 encoding, the string rotation, and the compression.

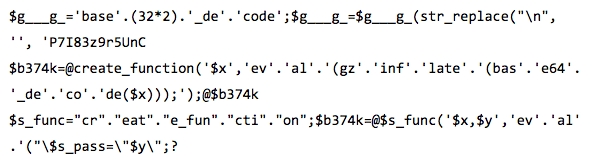

Knowledgeable adversaries understand that in order to bypass generic web application firewalls (WAF) or other network sensors, craftiness in evaluating the web shell string is required. A few examples of creative function calling from the web appear below.

Any technology that relies on signatures for detection is going to be moderately effective. Since the web shell itself does not exhibit malicious characteristics (especially when web shells are used in a forward fashion with no reverse connect or beacon to a controller), it is the adversary behavior that is left to profile for higher-level choke points. Web shell authentication is one such useful adversary tactic.

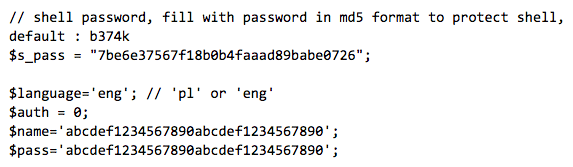

Most web shells provide options for user authentication; adversaries use authentication primarily to prevent other actors from taking control of the web shell. A search of the previous un-obfuscated PHP files returns almost universal results for some combination of the variables: user, auth, login, and/or pass.

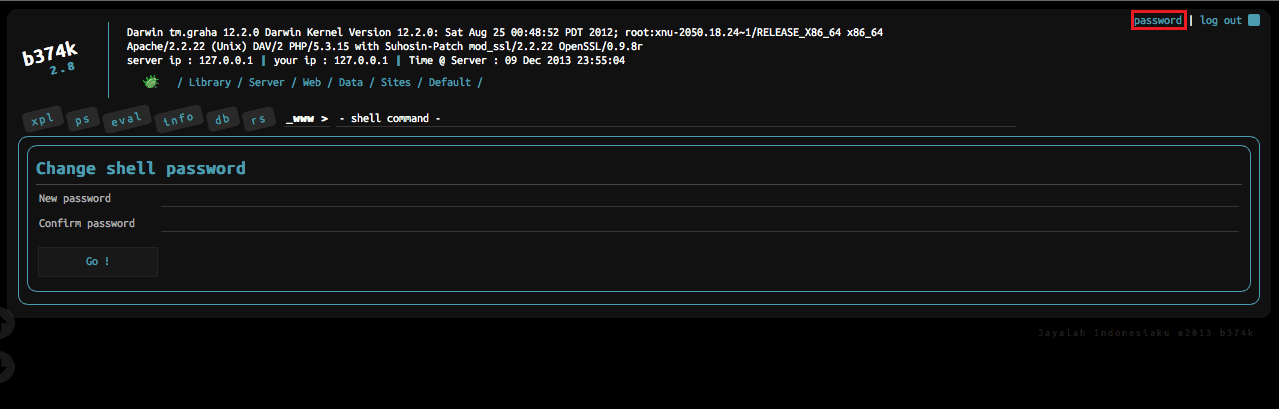

Changing the b374k web shell password — https://github.com/b374k/b374k.

All of the these web shells use basic, form, or digest HTTP authentication. This presents a real opportunity to apply a high-fidelity methodology to HTTP traffic analysis. Web proxy logs are particularly useful for identifying HTTP authentication sessions.

In addition to catching web shell activity, alerting on basic HTTP authentication will identify internal applications that should be modified to include SSL or else discarded and blocked from future installation. It’s also an opportunity to alert employees to the dangers of using specific insecure external websites.

Bro is a free tool that can easily catch all HTTP authentication in the network because it includes default protocol parsers that produce logs (e.g., ~/bro/http.log) based on user applied rules. There are a number of proof-of-concept rules for alerting on successful HTTP authentication that are good templates for crafting a rule that is tailored to a specific enterprise environment.

If enterprise web servers use a central user repository (like Active Directory) for access policies, then usernames could be stripped out of HTTP bro logs and compared to a known list of existing (authorized) users (extracted using PowerShell). Further analysis is warranted whenever usernames are found in Bro logs (due to successful HTTP authentication), and doubly so when those same usernames are not found in the Active Directory result list.

Certainly not every web shell uses a username field and some malicious web shell users may bypass authentication all together, as seen below.

There are no silver bullets for web shell detection, but a multi-pronged strategy of continuous infrastructure awareness, server hardening, and leveraging threat intelligence to profile adversary network behaviors is a winning recipe for persistent web shell prevention.

Conclusion

Real-time threat intelligence harvested from the web is a powerful capability for identifying emerging trends in adversary use of web shells. Web servers continue to be an attractive target to accomplish adversary objectives and web shells accomplish a range of tasks while ensuring persistence in the victim network.

Presently, derivatives of the WSO and b374k web shells are the most frequently mentioned open source web shells.

Analysis of over 250 un-obfuscated PHP web shell files returns little commonality and therefore limited opportunities for broad family string-based detection. Instead, web shell user behavior reveals an opportunity to catch web shell placement in the network through successful basic HTTP authentication.

Preventing persistent web shells requires a multi-faceted strategy that begins with in-depth knowledge of internally managed web servers and their respective content. Savvy defenders profile adversary behaviors and craft high-level operational defenses capable of detecting broad web shell activity.

The second part will include an analysis of CKnife, a new Chinese web shell taking inspiration from China Chopper and implementing new features. Stay tuned!

Related