Russian Invasion of Ukraine and Sanctions Portend Rise in Card Fraud

This report analyzes technical, political, and socioeconomic factors contributing to the scale of card fraud conducted by Russia-based threat actors within the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The sources for this report are Russian-language dark web forums and Telegram channels, information provided by the Ukrainian government, and open-source reporting. The intended audience of this report is fraud and CTI teams in the financial sector that wish to understand how the Russian invasion of Ukraine may affect the scale of card fraud activity.

Executive Summary

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has created a humanitarian crisis and caused immeasurable human suffering. In response, Western countries have imposed sanctions on Russia, and many global companies have chosen to cease or severely limit the scope of their operations in Russia. These measures have drastically limited the flow of financial transactions between Russia and the West. Unfortunately, from the perspective of card fraud — one of the most pervasive forms of financially motivated cybercrime — these measures do not prevent Russia-based threat actors from compromising payment cards or monetizing cards through cashout schemes.

Furthermore, analysis of the current political and socioeconomic dynamics occurring within Russia indicates that these dynamics are creating conditions conducive to an increase in card fraud by Russia-based actors. The political factors are driven by the highest level of confrontation between Russia and the West in decades, creating the conditions for the Russian government to consider foreign-facing cybercrime as an asset in the confrontation. The socioeconomic factors are driven by the economic crisis sweeping through Russia, creating conditions for:

- Individuals without technical expertise to view compromised payment cards as a feasible way to finance purchases and a method to pay for digital services that no longer accept Russia-issued cards

- Members of Russia’s large and highly skilled IT community to supplement or replace lost income through cybercrime, including the compromise and sale of payment cards

Key Judgments

- Western sanctions imposed on Russia, the decision by major global card networks to only allow intra-Russia transactions, and the exit of several internet service providers from Russia do not create a new technical barrier for Russia-based threat actors to compromise, sell, and monetize payment cards.

- The Russian invasion of Ukraine and resulting confrontation between Russia and the West have generated political conditions in which the Russian government may reverse the recent policy decision to prosecute Russia-based cybercriminals, opting instead for indifference or even active support.

- The economic crisis in Russia, combined with Russia’s significant IT sector and confrontation with the West, has generated socioeconomic conditions in which individuals with IT training — or simply in search of supplemental income — may be more incentivized to engage in financially motivated cybercrime, such as carding.

- Threat actors have already begun exploiting the humanitarian disaster in Ukraine and large-scale migration to monetize compromised payment cards via a modified version of “travel fraud”.

Russia Cracks Down on Cybercrime, Then Invades Ukraine

In response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Western governments have implemented severe sanctions against Russian individuals, companies, and the financial sector. These sanctions have already destabilized the Russian economy, resulting in a sharp depreciation of the ruble and inflationary pressure.

These sanctions have been accompanied by the decision of private companies to partially or completely cease their operations in Russia. In the context of financially motivated cybercrime, the most relevant of these companies have been major card networks (Mastercard, Visa, and American Express) and internet service providers (Cogent and Lumen). The card networks have all announced that they would no longer allow Russia-issued payment cards on their networks to conduct transactions with merchants located outside of Russia. The internet service providers, which facilitate the flow of data on the internet, announced that they would no longer provide direct services within Russia.

Prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Russian-language portion of the dark web had already been thrown into a state of chaos by Russian law enforcement’s hitherto unprecedented decision to crack down on prominent ransomware actors and operators of dark web carding marketplaces. The crackdown began in January 2022 and continued through to mid-February 2022, culminating in the arrest of several REvil members and the closure of several carding marketplaces. The crackdown had a chilling effect on the Russian dark web, causing several marketplaces to preemptively close in order to avoid possible prosecution and other marketplaces to pause operations while they moved their infrastructure out of Russia.

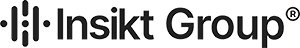

Figure 1: A banner placed by Russian LE on the dark web carding marketplace Ferum Shop’s site announcing that the domain has been seized. Russian LE placed the same banner on the sites of other marketplaces, including Trump’s Dumps, SkyFraud, and UAS Shop. (Source: Ferum Shop)

Figure 1: A banner placed by Russian LE on the dark web carding marketplace Ferum Shop’s site announcing that the domain has been seized. Russian LE placed the same banner on the sites of other marketplaces, including Trump’s Dumps, SkyFraud, and UAS Shop. (Source: Ferum Shop)

Will Sanctions and Global Companies’ Solidarity Prevent Card Fraud by Russian Threat Actors?

Russia has historically been a hotbed for card fraud targeting victims across the globe, with Russia-based actors compromising payment cards, operating dark web carding marketplaces, and monetizing compromised payment cards through various “cashout” schemes. While cybercriminals all around the world engage in card fraud, Russia-based actors have always had a disproportionate presence in the card fraud sphere. As a result, if Russian cybercriminals were prevented — or at least significantly encumbered from — engaging in card fraud, then it is likely that we would witness a significant decrease in the volumes of compromised payment cards offered for sale on the dark web.

This leads to the key question: Will sanctions on Russian financial institutions and the decision by major global companies to curtail operations in Russia create a technical barrier for Russian carders? The short answer: no.

To show why, we need to divide “Russian carders” into 2 categories: the sellers and the buyers. The sellers are those actors who actually compromise payment cards and then sell them on dark web marketplaces, whereas the buyers are those that purchase the card records and monetize them. To put it simply, sanctions and the actions of global companies do not create a technical barrier for sellers, especially given the fact that threat actors have always been at the forefront of methods to bypass internet and geolocation restrictions. For buyers, the measures will introduce technical barriers for cashout schemes in which monetization occurs in Russia, but ultimately allow other cashout schemes in which monetization occurs outside of Russia to remain open.

Sellers: Magecart E-Skimmers, Database Dumping, and POS Device Malware Campaigns

As mentioned above, the sellers are those actors that compromise payment cards and then sell them on dark web marketplaces. Traditionally, cybercriminals needed a high degree of technical expertise to hack into point-of-sale (POS) devices, “dump” databases, or inject e-commerce sites with Magecart e-skimmer scripts. However, with the rise of dark web “anything-as-a-service” criminal offerings, less sophisticated actors can deploy “e-skimmer kits” (Magecart as a service) and simplified phishing solutions (phishing as a service) to compromise card-not-present (CNP) records.

From a technical perspective, threat actors only need access to the “global internet” to compromise payment card records through Magecart infections, “dumping” databases containing payment card data, or remotely infecting POS devices. So far, Russia-based threat actors still have access to the global internet despite the decision by the internet service providers Lumen and Cogent to curtail operations in Russia in early March 2022. These companies, together with other companies in the sector, serve as the backbone of the internet, facilitating the transfer of internet data across geographic regions. Lumen’s customers included major Russian telecommunications companies, enabling those companies to connect Russian internet users with global networks. While experts expect Lumen and Cogent’s exit to increase bandwidth congestion for the Russian internet, other companies offering the same services remain operational in Russia, thereby allowing Russia-based threat actors to continue cybercrime activity targeting Western victims.

Buyers: Money Mules, Drops, and Cryptocurrency

The buyers are those actors that purchase compromised payment card records and then monetize them through cashout schemes. These schemes range from simple online purchases of goods and services to complex money laundering rackets involving networks of money mules. Ultimately, the core dynamic for buyers in card fraud (as opposed to bank fraud, which involves gaining access to online bank accounts) is how they convert — or “monetize” — compromised payment card data into material gain.

For Russian buyers, the simplest level of card monetization would be to purchase a subscription for a digital service (streaming sites, video game services, productivity platforms, etc.) with the card data. At this level, the only technical barrier — beyond existing anti-fraud measures implemented by financial institutions — is whether the given digital service exited the Russian market. However, in cases in which an individual knows how to buy a compromised record, they typically also know how to bypass geographic restrictions through VPNs and proxy servers. Furthermore, the latest data shows a sharp rise in Russian VPN use since the Russian government began implementing new bans on social media sites and news outlets. On the card network side of the equation, buyers would frequently be using non-Russian compromised payment cards, which means that the measures taken by the major card networks to prevent foreign transactions for Russian payment cards would not affect card fraud activity.

Of the more complex cashout schemes used by Russia-based actors, one that deserves the most attention due to its scale and financial harm is “physical good resale fraud”. In this scheme, the buyer uses compromised payment card data to purchase a good (anything from a phone to a lawnmower) then sells the good at a significant discount. The buyer then pockets the resale money as profit. To reduce the likelihood of triggering anti-fraud systems, the buyers typically deliver the purchased goods to a location as close as possible to the cardholder’s billing address and then have a money mule, or “drop”, receive the goods. Due to the fact that roughly 84% of compromised payment cards offered for sale on the dark web in the last year were issued by the US, Canada, UK, Australia, or an EU country, the majority of goods in this scheme are sent to one of those countries. From there, Russia-based criminal groups have 2 primary options:

- Sell the goods in the US or Europe through money mule networks that receive the purchased goods, resell them, and transfer a portion of the profits to the Russian criminal group.

- Instruct the money mule networks to reship the goods to Russia, where the cybercriminal group resells the goods on the Russian market. Now, with many international retailers exiting the Russian market, this option is likely to garner increased interest from Russian consumers without another method of obtaining certain goods.

Although several major shipping and freight companies recently announced that they would temporarily cease deliveries to Russia or only ship “essential goods”, cybercriminal groups — once again proving their capacity for adaptability — have been able to continue to reship goods to Russia, with threat actors advertising these services on dark web forums.

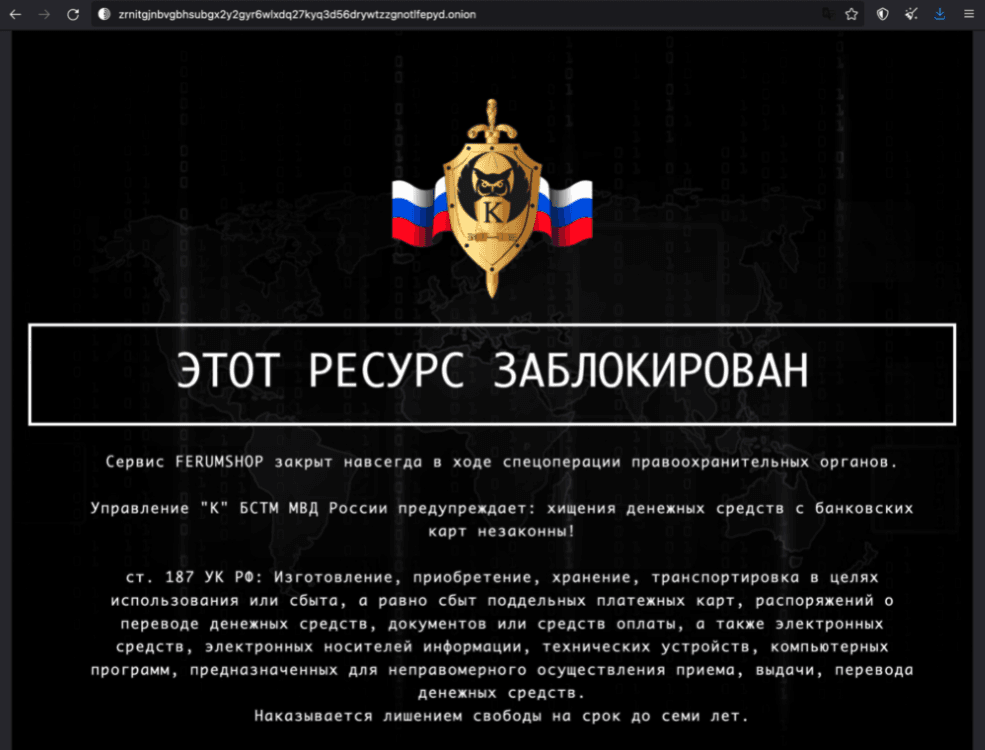

Figure 2: On March 23, 2022, a Russian-language dark web actor offers to purchase goods bought with compromised payment cards and then resell them, specifically claiming that they have the capacity to deliver these goods to Russia (Source: Verified forum — image text translated from Russian to English via Google Translate)

Figure 2: On March 23, 2022, a Russian-language dark web actor offers to purchase goods bought with compromised payment cards and then resell them, specifically claiming that they have the capacity to deliver these goods to Russia (Source: Verified forum — image text translated from Russian to English via Google Translate)

For these more complex cashout schemes that use overseas money mule networks, Western sanctions have created a technical impediment but not a full barrier. In the past, the money mules would deposit the profits from the resold goods in a “drop” bank account in the US or an EU country, then transfer the money to the criminal group’s bank account in Russia or a cryptocurrency wallet.

Now, with and heightened monitoring of EU bank accounts associated with Russian individuals, it is significantly more difficult for Western-based money mules to transfer funds to Russian banks. To get around this issue, Russian dark web actors are turning to opening bank accounts in nearby countries that have not implemented sanctions against Russia, such as Georgia, Kazakhstan, and Armenia. The cybercriminals could then use these bank accounts to receive profits from their money mule networks.

For transfers via cryptocurrency, Russian users are still able to receive payments to their wallets, but, due to currency controls implemented by the Russian government, they are not able to convert the funds into USD, which is preferable to the currently volatile ruble. To get around this issue, dark web actors have begun discussing converting cryptocurrencies into hard currency via relatively unregulated cryptocurrency exchanges housed outside of Russia and the West, with exchanges in the Republic of Georgia likely to play a large role.

Political and Socioeconomic Factors Create Conditions for Increased Card Fraud From Russian Actors

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the response from Western countries has generated several political and socioeconomic conditions that are conducive to card fraud. Although these conditions do not necessitate an increase in card fraud, their presence raises the likelihood of increased carding activity from Russia-based actors.

The political factors are driven by the highest level of confrontation between Russia and the West in decades, creating the conditions for the Russian government to consider foreign-facing Russian cybercrime as an asset in the confrontation. The socioeconomic factors are driven by the economic crisis sweeping through Russia, creating the conditions for cybercrime to become a comparatively attractive source of hard currency.

Political Factors: Government Co-Option or Support for Russian Cybercrime

Historically, Russia has been considered a “safe haven” for financially motivated cybercriminals because the government has generally pursued a policy in which cybercriminals were not prosecuted if they did not target victims within the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). In the buildup to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, this policy seemed to be changing with the arrests of several prominent ransomware actors and the shutdown of top-tier carding marketplaces.

In the wake of Russia’s invasion and the West’s strong support of Ukraine, the Russian government has given signals it is returning to a policy of non-interference with Russian cybercrime, with Vladimir Putin stating that the government would not prosecute “economic crimes” on March 5, 2022. Although Putin did not specify that cybercriminal activities like card fraud would not be prosecuted, threat actors on Russian dark web forums have already indicated that they do not expect interference and prosecution from Russian law enforcement.

One of the immediate results of non-prosecution by the Russian government for financially motivated cybercrime would be a resurgence in dark web carding marketplaces. While the shutdowns in January and February 2022 did not paralyze the carding marketplaces that serve as the brokers between sellers and buyers, the shutdowns did result in a short-term disruption that corresponded to lower volumes of cards posted for sale. Prior to the Russian invasion, analysts had already witnessed new marketplaces leverage the shutdown of top-tier marketplaces to carve out new segments of the carding market, but even vague signaling from the Kremlin that carding is fair game once again would likely drive an even faster marketplace rebound.

One of the most important questions emerging from these developments is whether the Russian government will follow a similar path to the one taken by North Korea, which, according to the US Department of Justice, has co-opted and directed cybercriminals to conduct financial cybercrimes on behalf of the regime. To date, there have been unconfirmed rumors on dark web forums that Russian law enforcement runs several forums, and there is widespread suspicion among Western security practitioners that ransomware groups historically operated with “tacit acknowledgment” from the Russian government. Even more worryingly, transcripts from the recently released “Conti leaks” go so far as to suggest collaboration between cybercrime groups and the government. As a result, the current fear is that the Russian government — or enterprising higher-ups in government agencies — may escalate from non-interference and tacit acknowledgment of cybercrime to active support and management of previously non-state financial cybercrime.

Furthermore, according to information provided to The Record by Natalia Tkachuk of the Ukrainian government agency National Security and Defense Council (Tkachuk requested that “Russia” and its forms be left uncapitalized in her responses):

[The Ukrainian authorities] are already starting to see that russia is developing and legalizing “cyber piracy” at the state level. In effect, law enforcement agencies are giving criminal hacker groups “indulgences” to steal funds from banks of other countries, primarily EU and NATO countries. Of course, this mechanism of theft can be used to replenish the hole in the economy of the aggressor country.

It is obvious that in Putin’s totalitarian russia, where everyone, including organized crime, is controlled by the intelligence agencies, independent (uncontrollable) hackers and marketplaces wouldn’t be able to hide for a long time without cooperation with them.

Socioeconomic Factors: Crisis Breeds Conditions for Cybercrime

The severity of the economic crisis facing Russia has affected all sectors of the economy, resulting in a sharp depreciation of the ruble and the imposition of capital and currency controls by the Russian Central Bank. The future course of the Russian economy remains dependent on various contingencies; however, the current economic crisis, combined with Russia’s significant IT base and the government’s potential indifference or endorsement of foreign-facing cybercrime, provides 3 conditions conducive to an increase in the number of individuals involved in cybercrime. According to reporting by Russian media, between 70,000 and 100,000 IT specialists have fled Russia since the outbreak of war; however, this number equals only 5-7% of the 1.3 million people employed by Russia’s IT sector (as of 2019), indicating that the vast majority of Russian IT workers have remained in the country.

In an interview with The Record, a Ukrainian government official confirmed that “among those IT specialists that remain [in Russia], there will usually be those who switch to … cybercrime”. The official stated that the Ukrainian authorities “predict the growth of cybercrime in the russian federation”, citing that “Moscow’s blatant disregard for the norms of international law in all spheres — including the fight against cybercrime and specifically, the Convention on Cybercrime — will certainly create favorable conditions for the domestic growth of cybercrime.” Furthermore, due to the fact that carding is considered one of the “lower rungs” of the cybercrime ladder, Recorded Future analysts expect that an increase in Russian cybercrime would correspond to an increase in Russian carding.

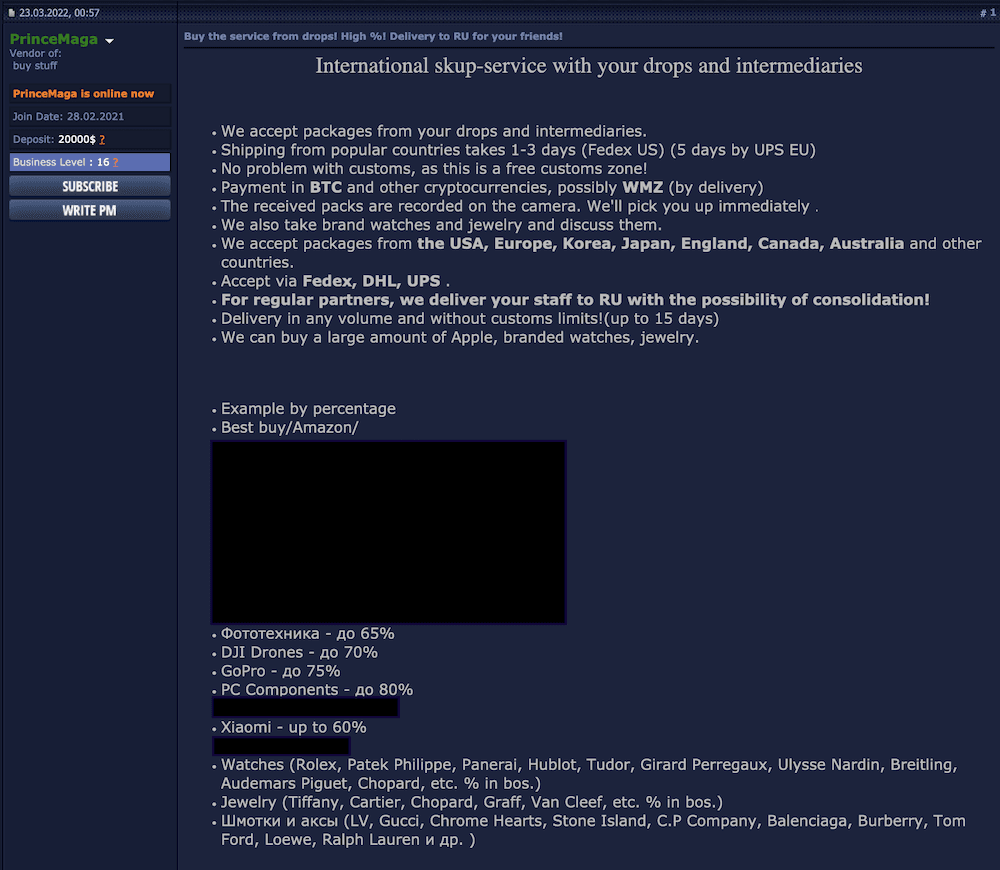

Additionally, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has triggered a humanitarian crisis, forcing nearly 4.8 million refugees to leave Ukraine as of April 15, 2022. While less significant, the war has also caused a wave of migration from Belarus and Russia; however, neither government has provided official statistics of the exact numbers yet. Threat actors have already begun to exploit the refugee crisis and migration to launch a modified form of “travel fraud”, providing yet another example of how cybercriminals adapt fraud schemes to changing circumstances.

Travel fraud refers to a fraud scheme where cybercriminals run fake “travel agencies” in which they use compromised payment cards to purchase flights, hotels, and recreational outings and then market them as legitimate, discounted offerings. With foreign travel by Russians projected to decrease in light of the depressed economy and the closure of airspace, these actors are reframing their “travel agencies” as discount options for housing and goods in European countries for Russian-speaking refugees and migrants. As shown in the images below, the actors operate their “agencies” through platforms like Telegram that are not necessarily criminal in nature, enabling them to attract customers who are in need of affordable services but do not realize that the offerings are in fact part of a fraud scheme.

Figures 3, 4: Russian-language Telegram channels, which are operated by actors with a presence on dark web forums, offer discounted food delivery and housing in Europe and around the world (Source: Telegram)

Figures 3, 4: Russian-language Telegram channels, which are operated by actors with a presence on dark web forums, offer discounted food delivery and housing in Europe and around the world (Source: Telegram)

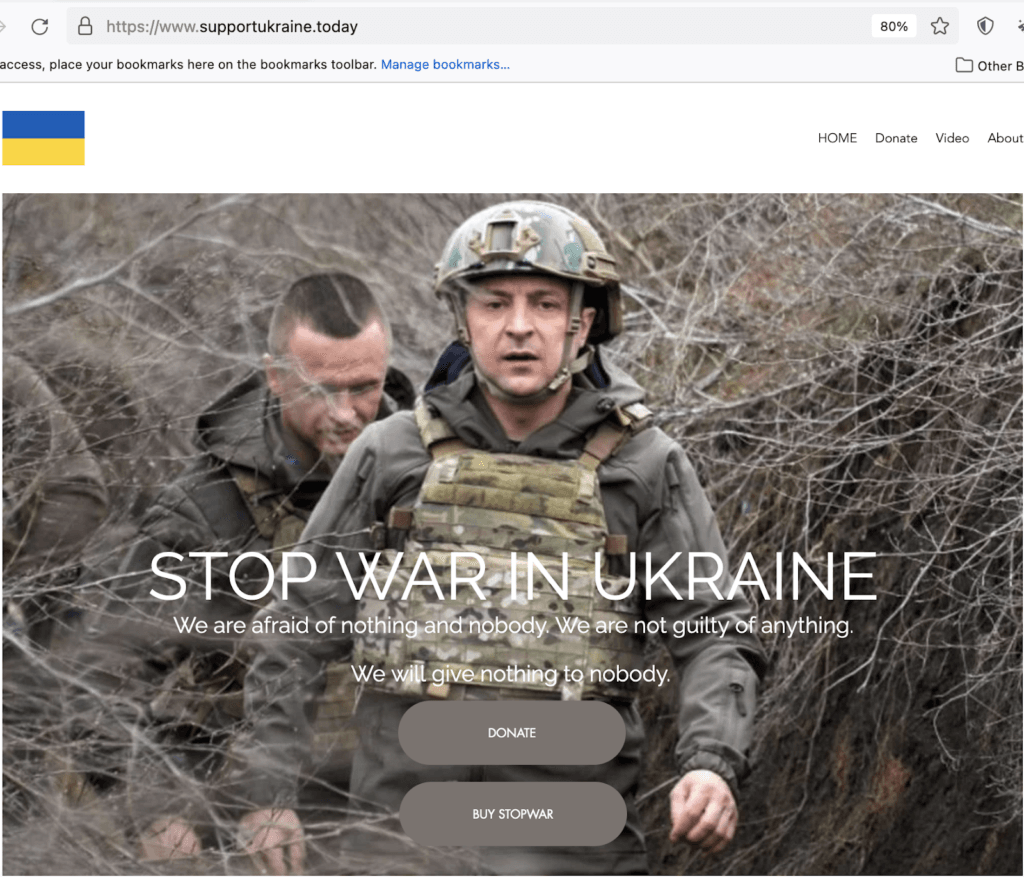

Beyond the modified form of travel fraud, analysts have also witnessed dark web threat actors adapt their phishing schemes by launching fake donation sites that exploit individuals who wish to support Ukraine. Cybercriminals typically run two types of fake e-commerce (or in this case, donation) sites: the less sophisticated versions only steal payment card data, while the more advanced ones are linked to merchant accounts under cybercriminals’ control, enabling them to pocket the proceeds and collect payment card data for later sale on dark web carding marketplaces.

Figure 5: Example of a fake donation site designed to deceive victims who wish to donate in support of Ukraine (Source: supportukraine[.]today)

Figure 5: Example of a fake donation site designed to deceive victims who wish to donate in support of Ukraine (Source: supportukraine[.]today)

Outlook

All of the technical, political, and socioeconomic factors covered in this report, and the likelihood of outcomes borne from the conditions that the factors generate, are highly contingent on the course of Russia’s war in Ukraine and the response by the international community and private enterprises. However, even in the event of peace in Ukraine, a highly confrontational relationship between Russia and the West would remain likely for an extended period of time, while a lessening of sanctions would be unlikely to immediately result in a revival of the Russian economy, especially within the context of Russia’s potential nationalization of foreign companies’ property and endorsement of economic theft. Under these scenarios, the conditions conducive to Russian government indifference or support for cybercrime and the increased involvement in cybercrime by the Russian population would remain in place, thereby raising the likelihood of increased carding activity from Russia-based threat actors.

Related