Restrictive Laws Push Chinese Cybercrime toward Novel Monetization Techniques

Editor’s Note: To read the entire analysis with footnotes, click here to download the report as a PDF.

This report analyzes the structure of internet sources used by Chinese-speaking threat actors to facilitate cybercriminal activities. It focuses specifically on advertisements, posts, and interactions on Chinese-language dark web marketplaces and cybercrime-related Telegram channels. It also takes into consideration the effect of Chinese laws and regulations on data security and cybercrime in China. This report is a follow-up to our previous reporting in 2021 on China’s cybercrime landscape and Chinese cybercrime in neighboring countries. It will be of greatest interest to organizations and geopolitical analysts seeking to understand the cybercriminal underground in order to better monitor security-related threats, as well as to those researching the Chinese-language underground.

Executive Summary

As China has continued to pass cybersecurity laws that give greater control to the state, this has inversely affected cybercrime as the companies that are usually targeted are being required to better secure personally identifiable information (PII) data. Nonetheless, PII data (of both Chinese nationals and international entities) is still being widely compromised and sold on dark web marketplaces, special-access forums, and Telegram channels. Furthermore, new laws banning cryptocurrency trading, the tightening of banking regulations, and a renewed crackdown on telecommunications (telecom) and online fraud continue to make it tougher for cybercriminals to operate in China. As a result, cybercriminals have moved their operations abroad and devised novel ways to weaponize PII data to perpetrate fraudulent activities.

We analyzed new Chinese-language dark web marketplaces that have emerged in the past year as well as popular Chinese-language Telegram channels devoted to cybercrime. We surveyed Chinese- and Taiwanese-related PII and access offerings on English- and Russian-language special-access forums and analyzed how they could provide initial access to ransomware threat actors. We also examined some unique scams in the Chinese cybercrime landscape and how they could be traced back to aforementioned dark web marketplace offerings. Finally, we provided some analysis on how geopolitical tension between China and Taiwan might shape cross-strait cyber conflicts in the coming years.

Key Judgments

- The enactments of China’s Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) and Data Security Law (DSL) signal that the Chinese government is serious about data security. The banning of cryptocurrency trading, mining, and advertisement, new regulations against money laundering, and new laws to combat telecom and online fraud are making it increasingly challenging for cybercriminals to operate in China as well as in neighboring countries.

- China’s drive toward a digital economy enabled by big data has opened up the attack surface for hackers and leaves data vulnerable, resulting in several high-profile data breaches leading to exposures of large numbers of PII data during the past year. It is highly likely that threat actors have harvested and analyzed big sets of data, organizing and parsing them into smaller sets of data that contain more specific groups and individuals in order to monetize them through cybercriminal sources.

- Despite the challenges noted above, Chinese-language dark web marketplaces continue to evolve, with new ones emerging to replace older ones that have gone offline. Telegram also serves an important role in the Chinese cybercrime scene, as it has been used to complement dark web marketplaces with threat actors who often advertise data sets and vice activities on their Telegram channels.

- As more leaked data from foreign countries appear on Chinese-language dark web marketplaces and more Chinese/Taiwanese data and access are posted on popular English- and Russian-language criminal sources, the national borders are increasingly blurred for cybercriminals.

- Chinese cybercriminals have become more organized in their transnational operations as they devise innovative ways to weaponize personally identifiable information (PII) to conduct fraud via sophisticated spearphishing schemes.

Background

Our previous reporting on the Chinese cybercrime landscape covered the Chinese-language dark web markets, clearnet hacking forums and blogs, and messaging platforms. We analyzed the features of these sources and the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) of Chinese-speaking threat actors within the context of their distinct cultural, political, and legal characteristics. In our reporting on Chinese cybercrime in neighboring countries, we uncovered the trend of well-resourced Chinese cybercrime syndicates moving their operations abroad, especially to Southeast Asian countries where the laws are more relaxed, which has enabled them to perpetuate fraud (such as online romance scams using the CryptoRom malware) on a global scale. As China marches toward a digital economy and enacts new laws and regulations to tighten data security and crack down on telecom fraud and cybercrimes, the environment becomes increasingly challenging for cybercriminals. However, new socioeconomic and technological developments present opportunities for cybercriminals who are constantly updating their TTPs to survive and thrive in the new landscape.

Threat Analysis

Laws and Regulations Affecting the Chinese Cybercriminal Landscape

In this section, we summarize various laws and regulations that went into effect during the past year that have a direct impact on the Chinese cybercriminal landscape, specifically the collection and storage of PII data by private companies, the Chinese government's continued crackdown on crypto use and mining, and laws designed to stymie activities that facilitate fraud and criminality.

The Enactments of PIPL and DSL

On November 1, 2021, China’s Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), which was passed by the National People’s Congress on August 20, 2021, went into effect. The PIPL is seen as the Chinese equivalent of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and was expected to add more compliance requirements for companies in the country. The Chinese government has instructed its tech giants to ensure better secure storage of user data, amid public complaints about mismanagement and misuse that have resulted in user privacy violations. The law stated that handling of personal information must have clear and reasonable purpose and shall be limited to the "minimum scope necessary to achieve the goals of handling" data. It also laid out conditions companies must abide by to collect personal data, including obtaining an individual's consent, and it also laid out guidelines for ensuring data protection when data is transferred outside the country. The law further called for handlers of personal information to designate an individual in charge of personal information protection, and also called for handlers to conduct periodic audits to ensure compliance with the law. The implementation of PIPL came after the passage of the Data Security Law (DSL), which came into effect on September 21, 2021, and set a framework for companies to classify data based on its economic value and relevance to China's national security. Together, PIPL and DSL provide 2 major regulations for governing China's internet in the future.

Didi Fined for Data Security Violations

On July 21, 2022, China’s internet regulator fined ride-hailing giant Didi $1.2 billion for its voracious data collection policies and lackluster security protections around sensitive user information.

The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) said it had concluded a network security review of the company and found “illegal activities” and violations of the country’s network security laws (DSL and PIPL). The fine was the largest data protection penalty ever issued by China, and the second-largest fine imposed on a Chinese technology firm after regulators slapped Alibaba with a $2.75 billion fine last year following an anti-monopoly probe.

The CAC said that during its investigation of Didi, which began in 2021, it found 16 violations that included the illegal collection of nearly 12 million users’ photo albums, 107 million facial recognition profiles of passengers, and significant amounts of users’ PPI data. According to Chinese regulators, Didi kept millions of sensitive user records unencrypted, causing “national security risks”.

The company’s app was also collecting “excessive” information on its drivers and often asked for device permissions that allowed widespread access to users’ devices. A spokesperson for the CAC criticized the company for having “inaccurate and unclear” descriptions of why it needed the information it was collecting.

The CAC said it plans to “intensify” its enforcement of cybersecurity and data protection laws in the coming years.

The Banning of Cryptocurrency Mining, Trading, and Advertisement, and the Introduction of Digital Yuan

While China has maintained a hostile relationship with the cryptocurrency industry since 2013, the latest crackdowns in 2021 were seen as the most severe. Citing concerns related to its effect on the climate, the State Council began calling for restrictions on crypto mining and trading in May 2021. Following the statement, provincial governments such as Inner Mongolia’s began to take proactive measures to eradicate crypto mining. As a result, miners in those regions were either forced to shut down permanently or to move to other crypto-friendly countries. In August 2021, the CAC ordered social media platforms to terminate 12,000 accounts that were promoting cryptocurrency “in the name of financial innovation”. The purged accounts spanned multiple platforms including Weibo, Baidu, and WeChat. It also shut down 105 websites that ran tutorials for cryptocurrency buying and selling. In September 2021, Chinese authorities ordered a fresh round of crackdowns on crypto mining and outlawed virtually all crypto trading activities.

In early 2022, the Chinese Central Bank issued the digital yuan (also known as the Digital Currency Electronic Payment (DCEP), e-Renminbi (e-RMB), and e-CNY), which was piloted in various Chinese cities during the second half of 2021 and made its global debut at the Beijing Winter Olympics in February 2022. It is a central bank digital currency (CBDC) that relies on blockchain technology to conduct transactions but is centrally controlled by regulatory authorities and backed up by fiat currency reserves. And unlike cryptocurrency, which offers a great deal of privacy and anonymity, the digital yuan gives the government unprecedented visibility into transactions as they have direct access to the data. It can also be made programmable so that the government can issue or cut off payments. 10 countries have already launched a CBDC and many more are considering it.

All Chinese-language dark web markets operate on cryptocurrency such as Bitcoin, Tether, and Ethereum. As detailed later in the dark web marketplace section, while we observed a number of such marketplaces going offline, new ones emerged to take their place. As a result of both government crackdowns in China and the issuance of the digital yuan, cryptocurrency trading will be pushed further into the underground and increasingly conducted on dark web marketplaces.

Regulations to Combat Money Laundering

A new regulation designed to combat money laundering was issued by China’s central bank and was scheduled to take effect on March 1, 2022. However, it was postponed due to “technical reasons”.

The new regulation requires people who make a single cash deposit or withdrawal that exceeds 50,000 yuan ($6,904 USD), or $10,000 USD in a foreign currency, to report the source and intended use of the money. Banks and other licensed financial institutions handling relevant transactions must also validate and store clients’ information, according to the joint order issued last month by the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission, and the China Securities Regulatory Commission.

Critics of the regulation claimed that it will effectively infringe on individual property rights by giving financial institutions the power to restrict deposits and withdrawals at their discretion, and may also mute capital flows and impede China’s economic recovery. Together with the ban on cryptocurrency trading, this new regulation makes it harder for cybercriminals inside of China to cash out their earnings.

Law Enforcement on Telecom and Online Fraud

On September 2, 2022,《中华人民共和国反电信网络诈骗法》(Law of the People’s Republic of China on Combating Telecom and Online Fraud) was passed during the 36th session of the Standing Committee of the 13th National People's Congress (NPC), and is set to take effect in December 2022.

The law was passed as telecom and online fraud grew more rampant in China during the past decade. The South China Morning Post reported that in recent years, criminals have illegally obtained victims’ information through advanced telecom network technologies and taken advantage of loopholes in management, and that this activity has become so rampant that it has posed serious threats to public security and social stability. Criminal syndicates have reportedly become better organized, with clear divisions of labor, and are able to conduct activities across multiple countries with the intention to scam people in China.

The law places major responsibility for anti-fraud security on telecom business operators, banking and financial institutions, non-bank payment institutions, and internet service providers. These organizations are expected to establish internal risk prevention, controls, and security systems. The law will be applicable both within and outside Chinese territory, and overseas organizations or individuals who conduct telecom network fraud activities will be held accountable in accordance with the relevant provisions of this law.

The law stipulates that the Chinese foreign and public security ministries must work more closely with international law enforcement agencies to crack down on these crimes. The law empowers the police to impose travel restrictions on suspects who frequently visit hotspot countries and regions, particularly Southeast Asian countries, unless they can provide valid reasons for their travel to such areas. Ex-offenders may also be subject to travel bans for as long as 3 years after completing their jail sentences.

The Drive toward Big Data and Major Data Breaches

According to the definition by Gartner, big data is “high-volume, high-velocity, and/or high-variety information assets that demand cost-effective, innovative forms of information processing that enable enhanced insight, decision making, and process automation.”

According to The Brookings Institution, many arms of the Chinese government have been collecting huge volumes of data for surveillance purposes, which authorities refer to as “visualization” (可视化) and “police informatization” (警务信息化). China’s data-fusion programs allow its surveillance systems to assemble highly detailed information of its citizens. The Chinese government makes use of data-fusion tools to monitor, collect, and store information of individuals classified as “focus personnel”, which includes “individuals petitioning the government, those purportedly involved in terrorism”, and those deemed by the Chinese government to be “undermining social stability”. These data-fusion tools have also helped to build predictive policing systems in Xinjiang, Brookings notes, helping to “‘accurately depict’ terrorists’ ‘religious, organizational, and behavioral characteristics’”.

Excessive monitoring, collecting, and storing of sensitive information belonging to individuals is not illegal under Chinese law. Under Article 28 and 33 of the Personal Information Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China, the law allows for state organs, such as the Chinese police force, to handle sensitive information, and the scope and limits of what type of data the Chinese government can collect and/or store legally are up to the state organs to decide. The types of information involved include biometric identification, religious beliefs, PII, medical care, financial accounts, individual whereabouts, and other information, as well as the personal information of minors under the age of 14.

The development of the big data industry was also seen as a key aspect of the 14th Five-Year-Plan period [2021-2025] as China’s industrial economy moves toward a digital economy. The big data industry had an average compound annual growth rate of over 30% during the 13th Five-Year Plan period [2016-2020]. New requirements were proposed for the development of the big data industry to allow it to enter a new phase of integrated innovation, rapid development, in-depth applications, and structural optimization. The drive toward big data was further accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, security is unable to catch up with the rapid growth of data collection, as evidenced by some high-profile data breaches reported during the past year. Threat actors have managed to obtain large volumes of data that contain extremely sensitive information, and then analyzed and repackaged these data sets into smaller data sets that have been resold on both Chinese- and non-Chinese-language cybercriminal sources.

Data Breaches of Beijing and Shanghai Health Code Apps

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, China has required its citizens to use an app on their smartphones that acts as an e-passport to dictate whether they should be allowed in public or be quarantined. The app was first heralded by the local government of Hangzhou with the help of Ant Financial, a sister company of the e-commerce giant Alibaba. The app generates a QR code in 1 of 3 colors: a green code enables its holder to move about unrestricted; a yellow code means the holder may be asked to stay home for 7 days; and a red code means a 2-week quarantine. An analysis of the app’s software code by the New York Times showed that in addition to determining in real-time whether someone poses a contagion risk, the app also shared the user’s information with the police, raising privacy concerns. According to Maya Wang, a China researcher from Human Rights Watch, “China has a record of using major events, including the 2008 Beijing Olympics and the 2010 World Expo in Shanghai, to introduce new monitoring tools that outlast their original purpose”. Maya Wang also added that “The coronavirus outbreak is proving to be one of those landmarks in the history of the spread of mass surveillance in China”.

In addition to privacy concerns, poor security in the databases associated with the health code apps had led to 2 well-publicized data breaches, described below.

On April 28, 2022, Wei Bin, an official from the Beijing municipal government, disclosed that Beijing Jiankangbao (北京健康宝), a mobile-based app used to check health codes and provide nucleic acid testing results during the COVID-19 pandemic, was allegedly attacked by overseas hackers. "The Beijing Jiankangbao was attacked on Thursday morning during its peak visiting period. The team of technicians fixed the problems swiftly", Wei said at a news conference, adding, "We later found out the source of the attack was from overseas". Wei claimed that the app was also attacked by overseas hackers during the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics. To date, we have not seen data from the app being offered on dark web marketplaces or forums.

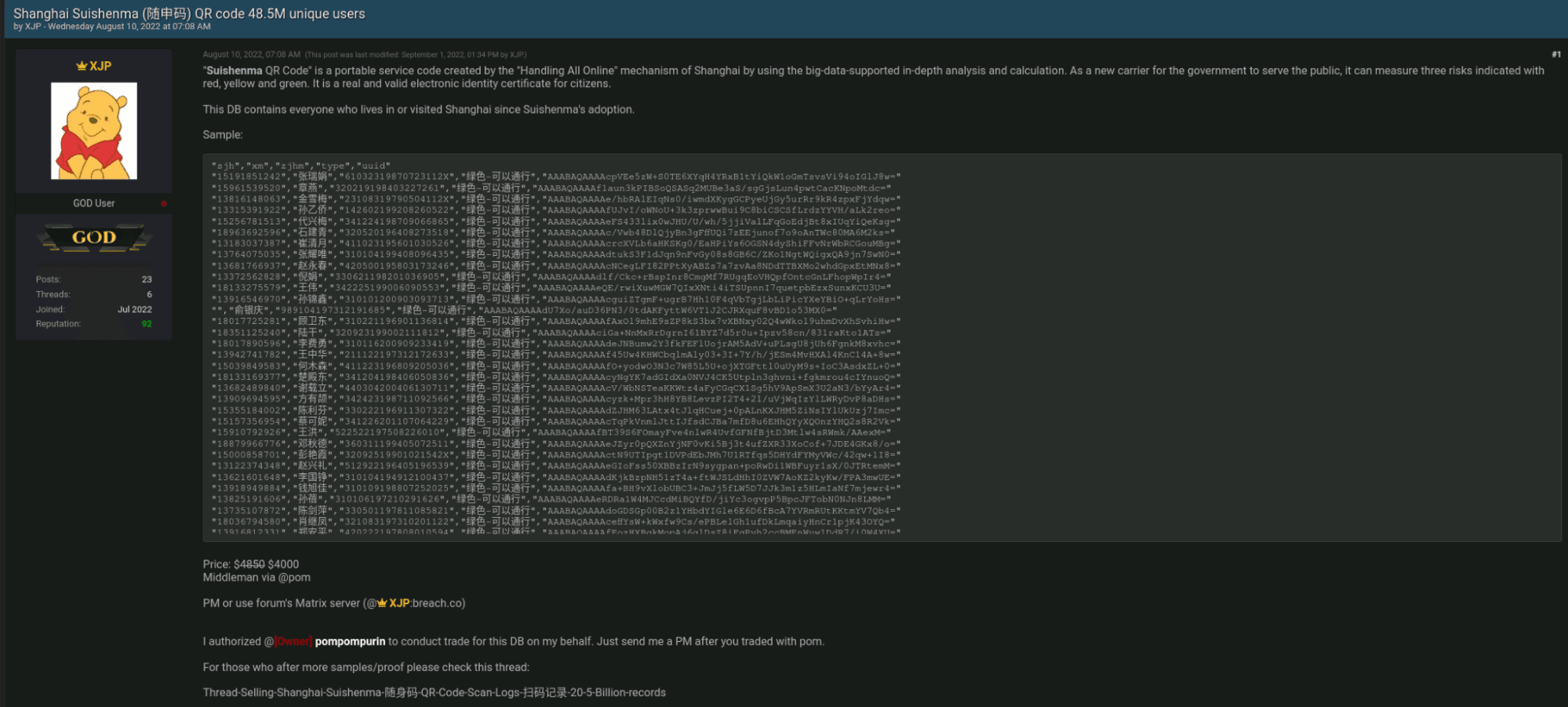

On August 10, 2022, “XJP”, a member of the mid-tier BreachForums, was selling data from 48.5 million unique users of 随身码 (Suishenma), the Shanghai equivalent of the Beijing health code that was compromised earlier this year. The Suishenma health code was developed by the Shanghai Big Data Center, an agency under the Shanghai Municipal Government, in early 2020 to help local authorities manage the COVID-19 outbreak. It became an essential digital tool in the daily lives of Shanghai residents, who were required to show a green code before being allowed to take public transport or to go into public venues. The threat actor XJP claimed the database contained everyone who lived in or visited Shanghai since the adoption of the Shuishenma app, and shared a screenshot of the data sample. The database was priced at $4,850, which was later reduced to $4,000. XJP uses Matrix (breach.co:XJP) as their primary method of contact. The post was listed as verified, and XJP authorized pompompurin, the administrator of BreachForums, to conduct the trade of this database on the threat actor’s behalf. While many comments to the post indicated interest in the database, most of them thought it was too expensive, even at the reduced price. It is interesting to note that the post used the Chinese characters 随伸码 (instead of the correct 随身码) to indicate the health code app, which suggested that XJP might not be a native Chinese speaker. On September 9, 2022, XJP also offered to sell data from China’s Border Exit and Entry Management Bureau that reportedly contained information on people who have crossed Chinese borders between July 2020 and July 2022. The threat actor stated that the database contains more than 240 million records, but that it may be incomplete and may not include data about diplomatic visits. The database was priced at $100,000. The credibility of XJP is moderate: the threat actor has authored 5 threads and 20 posts since registering their account in July 2022 and has a positive reputation score of 92, at the time of this report.

Figure 1: XJP selling QR health codes belonging to 48.5 million residents in Beijing, China (Source: BreachForums)

Shanghai Police Database Breach

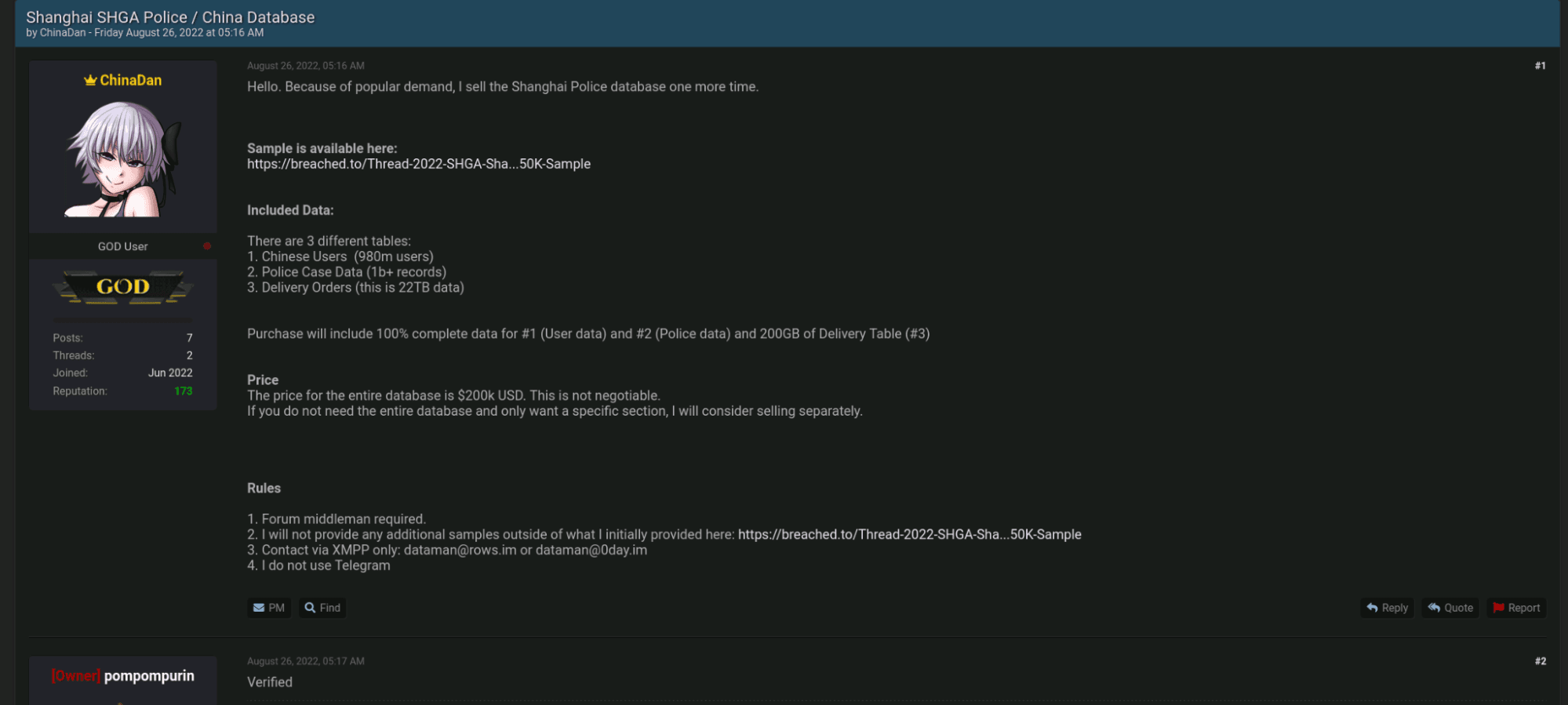

On July 3, 2022, news reports emerged regarding a data leak of 23 TB of personal information from the Shanghai National Police on Chinese citizens, posted by the user “ChinaDan” on BreachForums. According to Radio Free Asia, the leaked database was most likely hosted by Alibaba Cloud. As reported by Reuters, Zhao Changpeng, CEO of Binance, said on July 4, 2022, that the cryptocurrency exchange had stepped up its user verification processes after the company's threat intelligence detected the sale of records belonging to “1 billion residents of an Asian country on the dark web”, mostly likely referring to the BreachForums posting by ChinaDan.

Recorded Future has obtained the sample data shared by ChinaDan, and can confirm that the data includes full names, home addresses, birthplaces, national ID Numbers, mobile numbers, and crime/case details that date from as far back as 1995 to as recent as 2019. Our preliminary assessment of the data sample indicates that the data appears to be authentic. However, given the purported size of the data package, it is impossible to ascertain whether the entire package is what it is advertised to be.

Figure 2: ChinaDan selling the Shanghai Police databases on BreachForums; the owner of BreachForums pompompurin has verified the database to be legitimate (Source: BreachForums)

Chinese Database Storing Millions of Faces; Vehicle License Plates Left Exposed Online

On August 30, 2022, TechCrunch reported that a Chinese database that stored millions of faces and vehicle license plates was left exposed on the internet for months before it quietly disappeared in August 2022. The database, which reportedly held over 800 million records at its peak, belonged to a tech company called Xinai Electronics based in Hangzhou. The company builds systems for controlling access for people and vehicles at workplaces, schools, construction sites, and parking garages. Xinai Electronics had amassed millions of face prints and license plates through its network of cameras all over China, and claimed its data was “securely stored” on its servers.

The exposed data on an Alibaba-hosted server in China was found by security researcher Anurag Sen, who asked TechCrunch for help in reporting the security lapse to Xinai. Sen reported that neither the database nor the hosted image files were protected by passwords and could be accessed from the web browser by anyone who knew where to look. After several emails by TechCrunch notifying Xinai about the exposed database without replies, the database became inaccessible by mid-August 2022.

While we did not identify any postings on cybercriminal markets that directly mention this database, advertisements for car-owner information are often found on Chinese-language dark web marketplaces. For example, we found this posting of detailed information about General Motors car owners in China. We cannot ascertain if the data offered here came from the exposed database mentioned above, as it is a common practice for Chinese threat actors to parse large leaked databases into smaller sizes based on certain attributes in order to monetize it more easily.

DDoS Attacks and Hacktivism Surrounding Pelosi’s Visit

On August 3, 2022, the United States (US) House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan and met with Tsai Ing-wen, the president of Taiwan (Republic of China). Pelosi declared that the US “will not abandon our commitment to Taiwan” and Tsai said Taiwan would "never back down" in the face of threats. Throughout the day on August 2, 2022, and into August 3, 2022, China continued its strong warnings against Speaker Pelosi’s visit and took political, military, and economic actions aimed at punishing Taiwan and deterring further US support for Taiwan. On August 4, 2022, The Record by Recorded Future reported that Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defense said its network was taken offline by a distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) incident for about 2 hours following Speaker Pelosi’s visit to the island; the attack started shortly after Pelosi left the island. The Record article states that “Chinese government officials were furious about the visit — the first by a high-ranking US official in 25 years — arguing that it violated the country’s ‘one China’ policy”. In a statement, Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defense said the DDoS attacks began around 23:40 and ended around 00:30 (Taipei time). The ministry said it was working with other agencies and the president’s office to defend the government’s information security infrastructure. The attack came after several websites run by the government of Taiwan, including the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, as well as the Taoyuan International Airport, were disrupted ahead of Pelosi’s visit.

The attacks were large enough to make the websites inaccessible for brief periods, but were not particularly large in scale. ISC Sans and other cybersecurity organizations suggested the DDoS attacks were likely the work of nationalist hacktivists in China rather than China’s formal civilian or military cyber forces.

Despite the lack of evidence for any large-scale government-sponsored cyberattacks, John Hultquist of Mandiant still expected China’s cyber espionage “to kick into ‘overdrive’ as its government seeks to learn ‘what the US is thinking, what the limits of our resolve are’”, and stated that “‘the way you find answers to that are by reading emails of diplomats and military members and government leaders’”.

We did not find any direct mentions of DDoS attacks against Taiwan on the Chinese-language underground. However DDoS tools, tutorials, and services are often advertised on Chinese-language cybercriminal marketplaces. Anyone interested can easily acquire the tools and knowledge to pull off a small-scale attack.

Changes in the Dark Web Markets

Since our last report on the Chinese cybercrime landscape in 2021, there have been noticeable changes in the makeup of dark web marketplaces. Several of the marketplaces have gone offline, including Loulan City Market, Tea Horse Road Market, Ali Marketplace, and Dark Web Exchange. However, some of the accompanying Telegram channels for these marketplaces continue to operate. There could be a number of reasons for these dark web marketplaces going offline, which include but are not limited to law enforcement actions, exit scams, and internal disagreement between threat actors.

Marketplaces that are still operating at the time of this report include the Exchange Market, FreeCity Market, Alibaba Market, and United Chinese Escrow Market (UCEM). Meanwhile, 3 new dark web marketplaces have emerged and are still in operation at the time of this report: Dark Web Chinese Market, Tengu Market, and Chang’An Sleepless Night. Below are the descriptions of each of these 3 new marketplaces.

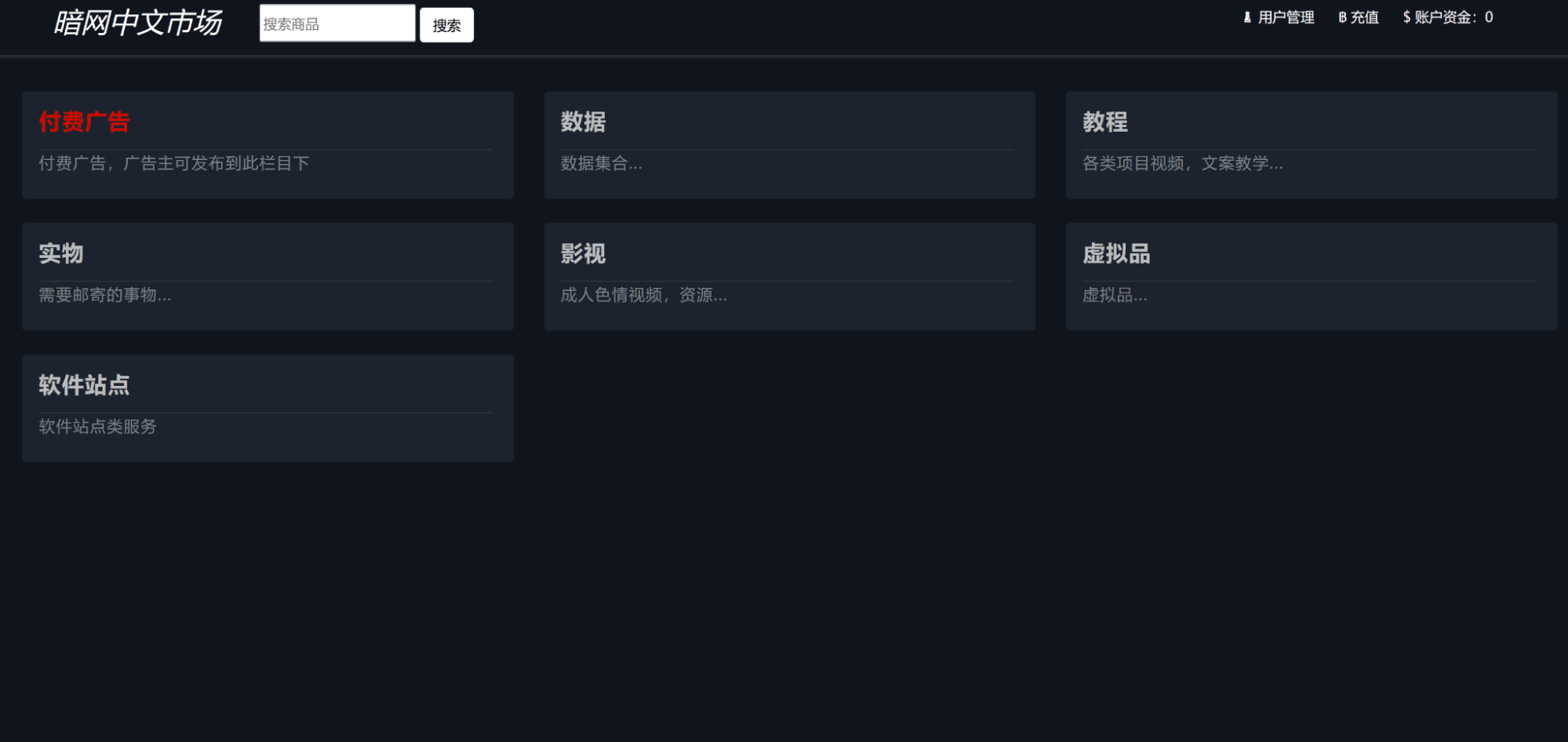

Dark Web Chinese Market

The earliest post on the Dark Web Chinese Market was from September 2021. Registration for the marketplace is free and listings are divided into the following categories:

- Paid Advertisement (no listings under this section at the time of this report)

- Data: Various stolen data including PII, carding material, and more

- Tutorials: Hacking techniques, social engineering, fraud schemes, and more

- Physical Items: Mostly sets of 4 IDs (standard for bank account access in China) for bank account access

- Videos: Mostly adult content

- Virtual Items: Carding tutorials, templates for counterfeit documents, and more

- Software Websites: Various legal and illegal software, SMS receiving services, and more

There were 700 items for sale at the time of this report, with postings listed in US dollars as well as Bitcoin (BTC). A for-sale posting has information including the number of items sold, the rating of the item, and the time the item was posted. The information of the seller is completely anonymized (no handle for the seller is provided) for the sake of privacy protection.

The transaction escrow period is 5 days, as any transaction is automatically confirmed after 5 days. If an extension is needed, a user needs to specify “stop automatic payment from the system” on the order form. If delivery is delayed for more than a day from the seller, the buyer can request a refund and note the reason. If there is a dispute in the transaction, each party has 3 days to address the request. The party that does not reply in 3 days will lose the arbitration automatically. Due to the anonymous nature of the website, no administrator is identified based on available information.

Figure 3: The landing page for Dark Web Chinese Market (Source: Dark Web Chinese Market)

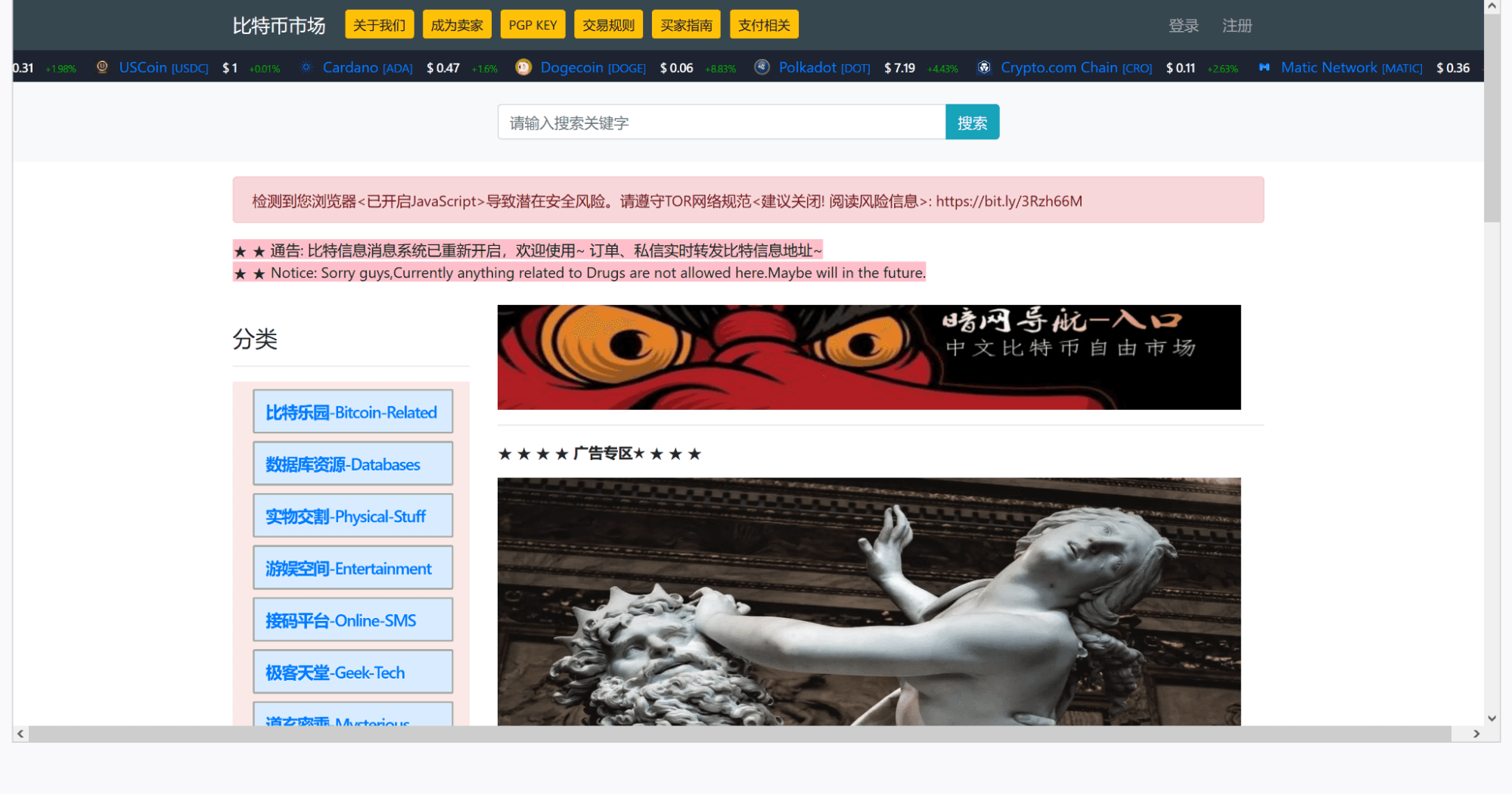

Tengu Market

The earliest seller registration on Tengu Market was dated from March 2022. Registration for the marketplace is free and listings are divided into the following categories (verbatim):

- BTC-Related: coin mixing services, cryptocurrency wallets without lost passwords, password crackers for wallets, and more

- Databases: email addresses with passwords, US driver’s licenses, blackhat search engine optimization (SEO) tutorials, and more

- Physical Stuff: cell phone cards, counterfeit watches, and more

- Entertainment: various types of games and software

- Online-SMS: Google voice numbers and other SMS receiving services

- Geek-Tech: remote access trojans (RATs), hacking tools and tutorials, and more

- Mysterious: carding materials and other tutorials

- Gift Cards: PayPal account numbers and passwords

There were about 60 postings at the time of this report, with postings listed in US dollars even though BTC is the only type of currency accepted. A for-sale posting has information including the number of items sold and remaining, the rating of the item, as well as the seller’s handle and rating. Each seller’s page has ratings in the categories of quality, communication, and delivery. The website charges a 7% processing fee for each transaction. After an order is placed on an item listed, if no payment is received after 5 hours, the transaction is automatically canceled. The website also offers arbitration for any disputed transactions. In addition, the website appears to have an associated chat room and Telegram channel. There does not appear to be a website administrator; however, the chat room has a member with the handle “管理员”, which is the Chinese word for “administrator”.

Figure 4: The landing page for Tengu Market (Source: Tengu Market)

Chang’An Sleepless Night

The earliest post on Chang’An Sleepless Night was from December 2021. Registration for the marketplace is free and listings are divided into the following categories:

- Paid Advertisement: a few listings including a solicitation to buy shopping and gambling data

- Data: Various stolen data including PII, protected health information (PHI), loan and retail data, and more

- Videos: Adult content

- Technical Skills: Hacking techniques, social engineering, fraud schemes, and more

- Carding and CVV: Carding material and tutorials

- Physical Items: Sets of 4 IDs for bank account access (standard for access in China), drugs, and more

- Services: Hacking, money laundering, and other illicit services

- Private Transactions: Private transactions between registered users

- Virtual Items: Leaked databases, account credentials, templates for counterfeit documents, and more

- Others: Miscellaneous tutorials and frauds

There were more than 1,600 items for sale at the time of this report, with postings listed in US dollars and BTC. Some items are also listed in Tether (USDT) and Ethereum (ETH). A for-sale posting has information including the number of items sold, the number of views, the handle of the seller, and the last time the seller was online. The marketplace offers escrow service, and transactions outside the website are discouraged. If an item purchased is not sent 3 days after payment, or if there is a dispute after the transaction, if the seller does not respond after 3 days, the transaction can be suspended by the buyer while notifying the administrator. After verification by the administrator, the cost of the transaction will be refunded to the buyer and the item will be taken offline. A certain percentage of the transaction proceeds will be deducted as a processing fee for website maintenance. The official Telegram channel of the market is @cabyc and the administrator can be contacted anonymously using the messaging service on the website or via Telegram at @ganmao.

Figure 5: The landing page for Chang’An Sleepless Night (Source: Chang’An Sleepless Night)

Below are some observations on the new developments on Exchange Market since our last report.

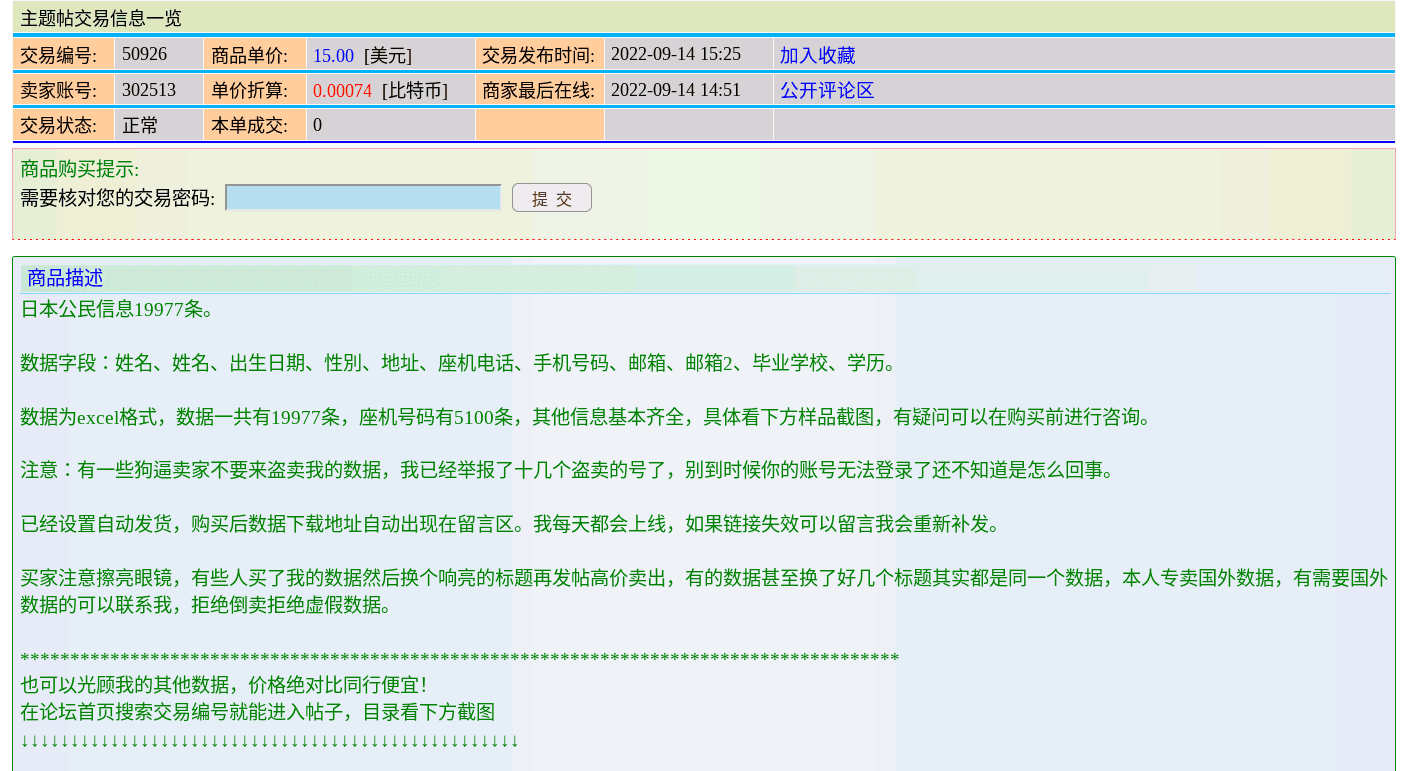

Greater Competition from Chinese Threat Actors on Exchange Market

2022 proved to be a popular time for Chinese threat actors to compete against the well-known Chinese threat actor “302513”, who has a moderate credibility on the Exchange Market, having more than 100 posts on leaked data affecting international entities since the relaunch of Exchange Market in Q4 2019. 302513 has indicated in their listings that reports have already been lodged against more than a dozen sellers, and that these sellers are recycling and reselling the data they bought from 302513. 302513 claims that other database sellers simply created new listings and resold the databases on the Exchange Market platform.

We observed that Exchange Market does not have any rules that clamp down on individuals that repackage and resell the data sets found in the platform’s listings. The platform lacks a protection mechanism for sellers like 302513, which has been hurting the financial profits of long-time database sellers. Such an observation also shows that Exchange Market is slowly evolving to become a more recognized platform for Chinese-speaking threat actors to market their database listings. As time goes by, we expect that more financially motivated threat actors will join Exchange Market and sell databases involving multiple countries and industries.

Figure 6: Exchange Market seller 302513 complaining about other Chinese threat actors recycling 302513’s data and reselling it on Exchange Market; the threat actor has lodged reports against more than a dozen sellers (Source: Exchange Market)

Chinese-Language Telegram Channels Devoted to Cybercrime

As stated earlier, some Telegram channels accompanying dark web marketplaces continue to operate even after those marketplaces have gone offline. Meanwhile, there are many independent Chinese-language channels that engage in carding, fraud, leaked data, and other illicit activities. While some of these channels initially disallow advertising, over time many channels, especially ones associated with dark web marketplaces, appear to be overrun by advertisements. The tables below list some of the Telegram channels associated with dark web marketplaces as well as ones that operate independently. The nature of these publicly accessible channels are mostly self-explanatory from their names. Additional intelligence is listed in the notes section, if warranted.

Telegram Channels Associated with Now-Defunct Tea Horse Road Market

| Name of Group | Membership | Notes |

| 茶马古道【数据交流】(Tea Horse Road [Data Exchange]) @Tea_group1 |

4,093 subscribers | |

| 茶马古道【黑产交流】(Tea Horse Road [Black Market Exchange]) @Tea_group2 |

2,060 subscribers | |

| 茶马古道【担保交易】(Tea Horse Road [Escrowed Transactions]) @Tea_group3 |

7,037 subscribers | Claims to conduct escrowed transactions and prohibits advertisements and chatting |

| 茶马古道【账号交流】(Tea Horse Road [Account Exchange]) @Tea_group4 |

2,429 subscribers | Sets of 4 IDs, QQ accounts, WeChat accounts, AliPay accounts, and more |

| 茶马古道【查档定位】(Tea Horse Road [Searching and Locating]) @Tea_group5 |

2,279 subscribers | For conducting online searches |

| 茶马古道【技术交流】(Tea Horse Road [Technical Exchange]) @Tea_group6 |

1,969 subscribers | |

| 茶马古道会员群【会员专属】(Tea Horse Road [Members Only]) @Tea_vip |

3,055 subscribers | A group for allegedly verified members of Tea Horse Market |

| 茶马古道【暗网综合】(Tea Horse Road [Dark Web Comprehensive]) @Cmsvip |

9,638 subscribers | Marked as a scam channel by Telegram |

Table 1: Telegram channels associated with Tea Horse Road Market (Source: Telegram)

Telegram Channels Associated with the Now-Defunct Loulan City Market

| Name of Group | Membership | Notes |

| 楼兰城-暗网楼兰城-暗网交易资源 (Loulan City - Dark Web Loulan City - Dark Web Exchange Resource) @uQJifwRpZ |

14,797 subscribers | |

| 楼兰暗网 OTC/USDT 担保交易所 (Loulan Dark Web OTC/USDT Escrow Exchange) @loulananwang |

8,190 subscribers |

Table 2: Telegram channels associated with Loulan City Market (Source: Telegram)

Telegram Channels Associated with the Now-Defunct 668 Market

| Name of Group | Membership | Notes |

| 668 暗网商城 |综合|担保 (668 Dark Web Market | Comprehensive | Escrow) @RR668 |

13,446 subscribers |

Table 3: Telegram channel associated with 668 Market (Source: Telegram)

Telegram Channels Associated with the (Active) FreeCity Market

| Name of Group | Membership | Notes |

| 暗网自由城自由交易 (Dark Web Free City Free Exchange) @Freecityescrow |

1,298 subscribers | Administrator is @freecityadmin |

| 暗网自由城官方担保交易市场 (Dark Web Free City Official Escrow Exchange Market) @freecitysocial |

5,545 subscribers | |

| 自由城暗网 教程 (Free City Dark Web Tutorials) @Freecitystudy |

1,260 subscribers | |

| 自由城骗子曝光 (Free City Scammers Exposed) @Freecityexpose | 226 subscribers | |

| 暗网自由城市场 咸鱼 小姐 资源 社工库 四套件 (Dark Web Free City Market, Salted Fish, Girls, Resources, Social Engineering Databases, Sets of 4 IDs) @Freecitysocial101 | 3,420 subscribers |

Table 4: Telegram channels associated with the FreeCity Market (Source: Telegram)

Telegram Channels Associated with the (Active) Chang’An Sleepless Night

| Name of Group | Membership | Notes |

| Cabyc 长安不夜城 暗网担保交易 防诈骗 绝对可靠 (Cabyc Chang’An Sleepless Night Dark Web Escrow Exchange, Prevents Scams, Absolutely Reliable) @cabyc |

5,212 subscribers | Administrator is @ganmao |

| 暗网担保交易 长安不夜城 官方频道 (Dark Web Escrow Transactions Chang’An Sleepless Night Official Channel) @cabycout |

397 subscribers |

Table 5: Telegram channels associated with Chang’An Sleepless NIght (Source: Telegram)

Examples of Independent, Chinese-Language, Fraud-Related Telegram Channels

| Name of Group | Membership | Notes |

| 扫号器 数据库 破解 数据 密正 撞库 (Scanners, Databases, Cracking, Data, Dictionary Attacks) @Saohaoqipojie |

6,065 subscribers | Administrator @jmpojie, VIP group requires paid membership |

| 暗中帝国国际网赚 (Dark Empire International Online Money Making) @anzhongdiguoxiangmu |

4,522 subscribers | |

| 加特林梳理 更新早知道 (Jia Te Lin Carding, First to Know the Updates) @cvvhv |

8,016 subscribers | A popular Chinese-language carding channel, admin @jiate |

| 数据-CVV-邮箱-12606,黑产交流与交易 (Data-CVV-Email-12606, Black Market Exchange and Transactions) @shuju1 |

6,693 subscribers | |

| Deep 暗网 tor 洋葱浏览器黑市外围灰产防骗举报投诉交易所 (Deep Dark Web Tor Browser Black Market Outside Gray Market Anti-Scam Reporting Exchange Market) @xxdeep |

6,178 subscribers |

Table 6: Examples of some independent, Chinese-language cybercrime Telegram channels (Source: Telegram)

China/Taiwan-Related Postings on English- and Russian-Language Forums

In addition to the aforementioned Chinese-language dark web marketplaces, China- and Taiwan-related compromised data and accesses are often advertised and sold on top- and mid-tier special-access forums such as Exploit Forum and BreachForums by established threat actors specializing in such sales. Some of these threat actors appear to be purely financially motivated and opportunistic while others appear to be ideologically driven. Ransomware actors rely on the use of compromised valid credential pairs to achieve remote access to compromised networks and launch their attacks. As more organizations have become aware of ransomware threats and pay more attention to data security, ransomware gangs have been expanding their targets and are no longer primarily focusing on organizations in the West. For instance, the notoriously prolific LockBit Gang had recently claimed several victims in China and Taiwan. Below is a list of data and initial access offerings recently posted on dark web or special-access sources.

| Threat Actor | Intelligence |

| “0b0ltus” | On January 3, 2022, 0b0ltus, a member of the now-defunct mid-tier Raid Forums, was selling 2.4 million hospital records (dated 2021) from an unspecified China-based hospital, or hospitals, that include the following PII: full names (Chinese), phone numbers, doctor information (identification numbers, names, locations, and more), and diagnosis data. The database is priced at $600, and the threat actor uses Telegram (@ob0ltus), Jabber (0b0ltus@conversations[.]im), and email (0b0ltus@protonmail[.]com) as points of contact. The credibility of 0b0ltus is high: the operator has authored 33 threads since registering on the forum in November 2019 and has a positive reputation score of 177. |

| “kelvinsecurity” | On October 13, 2022, kelvinsecurity, a member of the mid-tier BreachForums, was selling a 10,000-record email database related to Da Ai Television (daai[.]tv), a Taiwanese television channel. Compromised information includes the full email database as well as user email addresses and passwords. The threat actor did not specify a price openly and uses Telegram (@PoCExploiter) as their main point of contact. The credibility of kelvinsecurity is high: the operator has authored 131 threads and 164 posts since registering their account in March 2022. The account has received 495 endorsements on the forum. |

| “AgainstTheWest” | On September 5, 2022, BleepingComputer [reported](https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/tiktok-denies-security-breach-after-hackers-leak-user-data-source-code) that TikTok denied recent claims that it was breached by the hacking group “AgainstTheWest”, and claimed that the source code and data exposed was “completely unrelated” to the company. On September 3, 2022, AgainstTheWest, who had a history of making outrageous hacking claims against targets in China, Russia, and other countries who were against Western interests, started a thread on BreachForums claiming to have breached both TikTok and WeChat, and offered screenshots of alleged databases from both companies. TikTok denied it had been hacked and claimed the source code shared on BreachForums was not part of its platform, and suggested that the leaked user data could be obtained through scraping. Meanwhile, WeChat had not issued a response to the hacking claim. On September 6, 2022, AgainstTheWest was banned from BreachForums by pompompurin, the forum’s administrator, for failure to properly investigate the breach. |

| “Minori” | On January 5, 2022, Minori, a member of the now-defunct Raid Forums, was selling internal sources (SRCs), files, vulnerability reports, and other internal data from the China-based companies China Telecom, China Mobile, China Netcom, and CHINANET. The threat actor included screenshots and a list of projects from the companies that are included in the data, which is being sold for $350 in Monero (XMR). The threat actor uses XMPP (minori@0day[.]la) and Telegram (@reckendheck) as primary methods of communication. The credibility of Minori is high: the user registered in January 2021 and has a positive reputation score of 1250 after authoring 56 threads on the forum. |

| “Warma2022” | On August 12, 2022, Warma2022, a member of the mid-tier BreachForums, was selling 28 million records of information from medical practitioners (doctors, nurses, and students) from the haoyisheng[.]com and cmechina[.]net websites, including phone numbers, login names, passwords, email and physical addresses, profile pictures, and more, for $2,600. The threat actor listed Jabber (warma@rows[.]im) as a point of contact. The credibility of Warma2022 is low: the operator has not made any posts prior to this one since registering in August 2022 and appears to have been banned from the forum at the time of this report. |

| “orangecake” | On May 23, 2022, orangecake, a member of the top-tier forum Exploit, was auctioning VPN and RDP access to an unspecified company in Taiwan that specializes in pharmaceutical and medical production with $99 million in annual revenue. The starting price is $700 or it can be purchased immediately for $1,000. The credibility of orangecake is high: the operator has authored 21 threads and posts since registering their account in September 2021. The account has received 9 endorsements from many high-profile threat actors on the forum and has several indicated sales. |

| “zirochka” | On May 13, 2022, zirochka, a member of the top-tier forum Exploit, was auctioning RDP access with local administrator privileges to an unspecified Chinese company with approximately $12 million in annual revenue. According to the threat actor, the local network has approximately 17 devices and over 8.5 TB of data to be exfiltrated. The starting price is $50 or it can be purchased immediately for $70. The credibility of zirochka is high: the operator has authored 56 threads and posts since registering their account in July 2016. The account has received 4 positive endorsements on the forum and has many indicated sales. |

| “YourAnonWolf” | On June 20, 2022, YourAnonWolf, a member of the mid-tier BreachForums, was selling a leaked database of ChungHwa Telecom, the largest telecom company in Taiwan. YourAnonWolf claimed the database was hacked by the threat actor “SiegeSec” and is between 3 to 4 GB, including databases, source codes, documents, and internal user information. The post included the Telegram handle of SiegeSec (@SiegeSec) as a point of contact. The credibility of YourAnonWolf is moderate: the operator has authored 12 threads and posts since registering their account in March 2022 and has a reputation score of 31. |

Table 7: Threat actors selling databases and initial accesses belonging to Chinese and Taiwanese entities on mid-tier forums (Source: Recorded Future)

Scams Unique to the Chinese Cybercrime Ecosystem

For this section, we investigated cybercrimes conducted by Chinese cybercriminals, such as illegal lending practices to both Chinese and non-Chinese interests with exorbitant interest rates, conducting spearphishing attacks on foreign individuals, crypto romance scams, and scamming Chinese nationals based outside of China. We examined some of the more unique frauds perpetrated by Chinese threat actors and identified that in almost all cases there were novel ways to utilize PII data that were sold and circulated on cybercriminal sources. We identified evidence that threat actors have weaponized compromised PII by devising sophisticated social engineering and spearphishing schemes in which they impersonate Chinese officials and well-known corporate entities to scam individuals both within and beyond Chinese borders.

Chinese Illegal Lending Practices and Connections to the Dark Web

In March 2021, the South China Morning Post reported that a multi-billion-dollar criminal lending scheme resulted in 89 deaths in China. The scheme trapped people in illegal loan contracts that resulted in annual compound interests as high as 5,214 percent — one man reportedly borrowed 2,000 yuan ($305) before eventually owing 700,000 yuan ($107,000) in a vicious cycle of predatory lending. An unlicensed money-lending gang headed by a man named Wang Tao inked 3.36 million contracts with 475,000 people between March 2018 and March 2019. The illegal enterprise lured unsuspecting borrowers with enticing terms such as “interest-free for seven days” or “low threshold, fast loans” in contracts that often resulted in annual interest rates of between 1,303 percent to 5,214 percent if the borrower could not pay off their debt quickly. The gang also hired 24 debt collection companies that harassed, threatened, and intimidated victims and their family members for a commission. Authorities say this intimidation directly resulted in some victims taking their own lives.

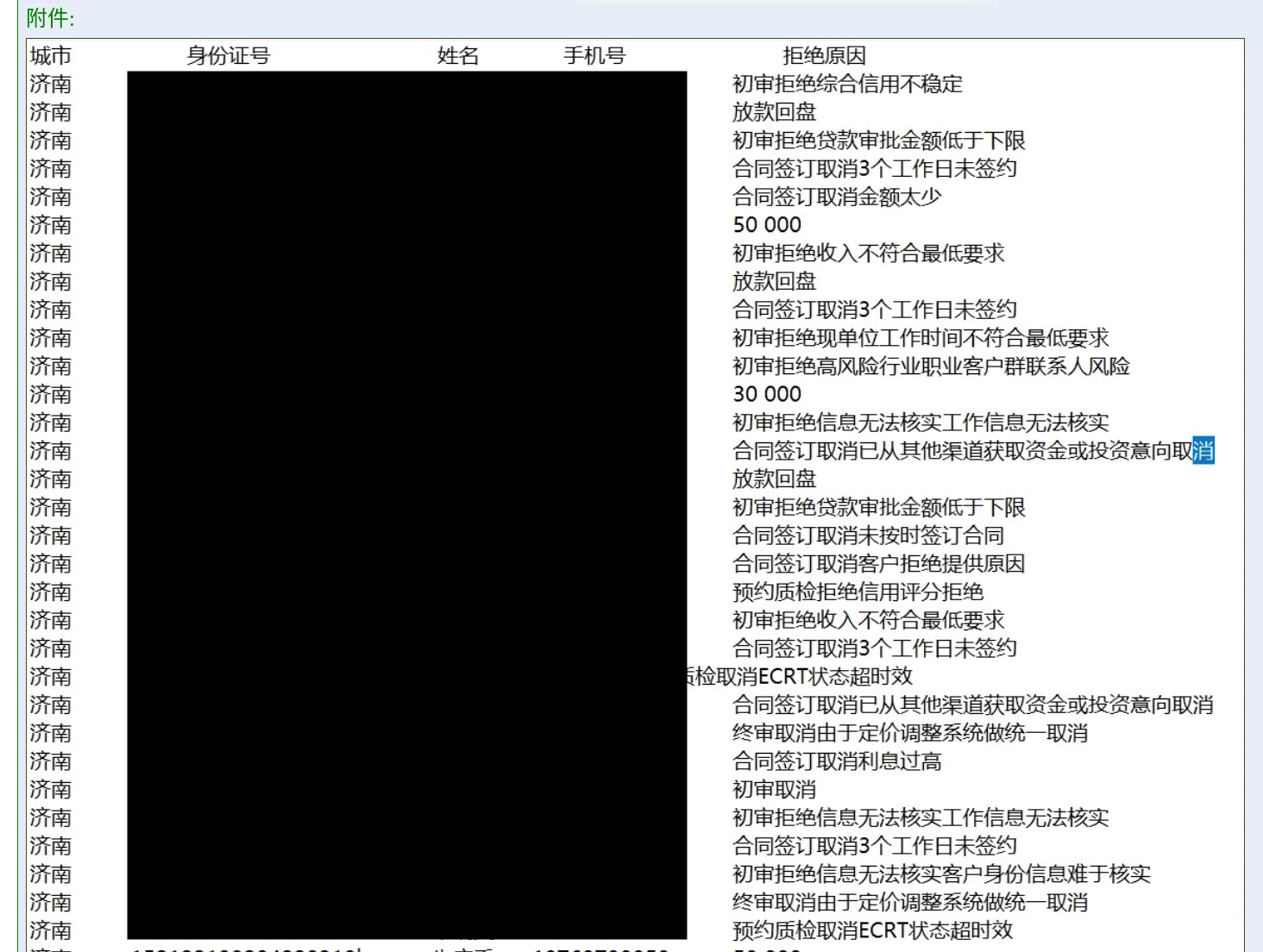

We found evidence from dark web marketplaces that threat actors have sold the PII of Chinese individuals with credit issues, and that the buyers of such data are highly likely to be related to loan sharks. We found that this type of information is likely stolen from a credit rating agency and can be used to exploit people with credit issues.

China’s “buy now, pay later” (BNPL) market has been growing, but there are downsides involved such as overspending (encouraging individuals to spend more than they planned to) as well as service providers charging a high fee for late payments. Some individuals may have difficulties servicing their debt obligations and may fall for online illegal lending schemes due to this type of PII being sold on the dark web.

| Type of PII | Intelligence |

| Individuals with credit issues | On September 15, 2022, “599731”, a member of Exchange Market, listed a database with more than 120,000 records of Chinese citizens who are bank loan rejectees for $39. Although the threat actor did not share the source of the data, the sample screenshots shared by the threat actor include the following data fields: full names, ID numbers, mobile phone numbers, cities where the bank operates, and reasons for rejection by the bank for loans. |

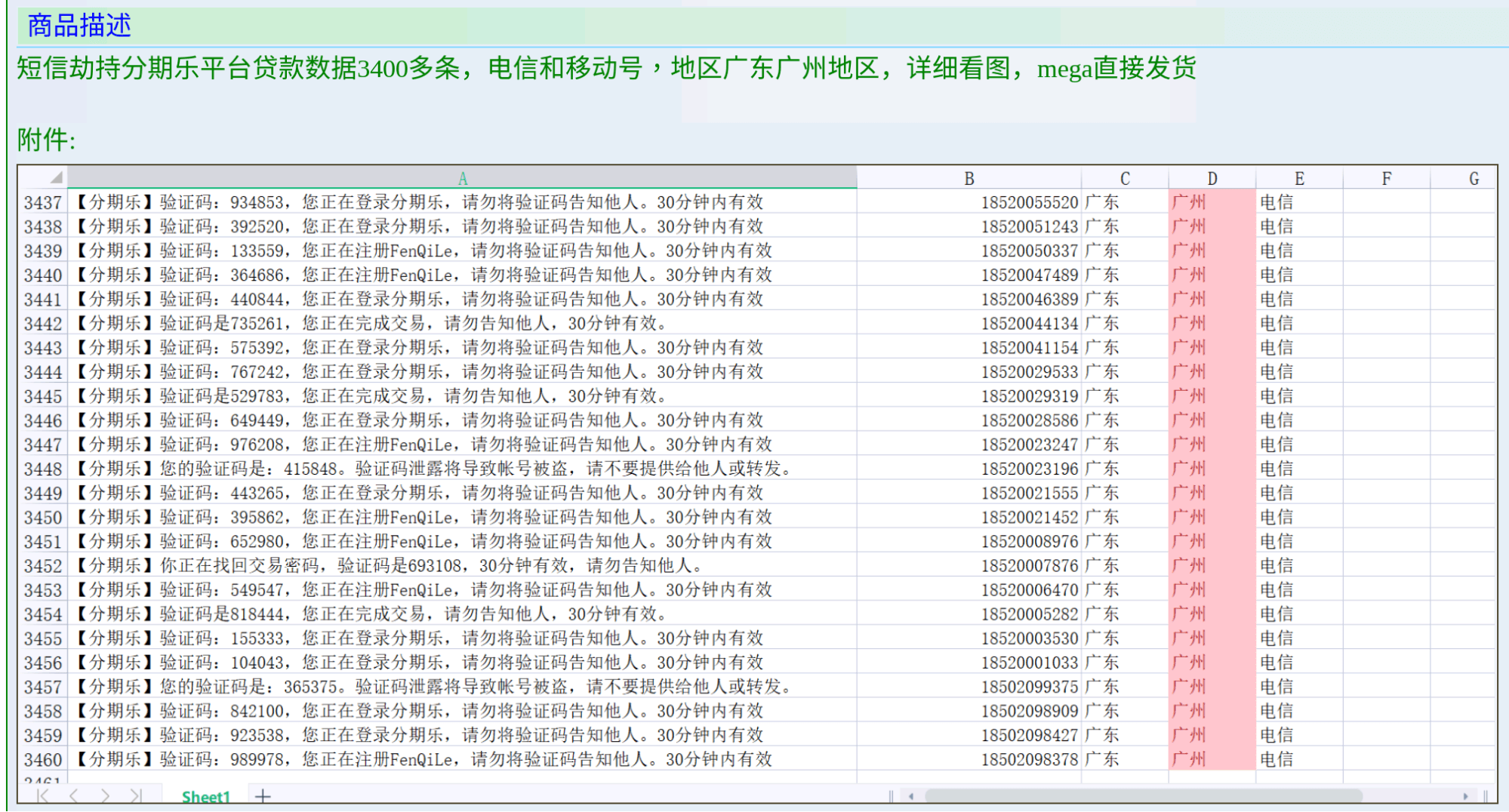

| Individuals that make purchases via installment plans | On September 22, 2022, “724984”, a member of Exchange Market, listed a database with more than 3,400 records of users from Fenqile (fenqile[.]com) for $25. Fenqile is a Chinese platform that helps to facilitate purchases via installment plans. The threat actor claims to have stolen the data through the use of SMS hijacking; the sample data also shows the 6-digit one-time password (OTP) numbers that users are required to input before logging into the Fenqile platform. The sample screenshots shared by the threat actor include the following data fields: 6-digit OTP codes required for login, phone numbers, and physical address data (state and city). The credibility of 724984 is moderate: the threat actor has made more than 100 postings on the Exchange Market since early August 2022. |

Table 8: Types of PII that would likely contribute to the devisement of scams targeting financially vulnerable individuals (Source: Recorded Future)

These types of PII would appeal to unlicensed money-lending gangs, who could contact these unsuspecting individuals by luring them with promises of low-interest and fast loans. The syndicates know that these groups of people have a higher tendency to be financially vulnerable as they were rejected by banks to take on any legitimate loans, or had to use installment plans to purchase items. Knowing the reasons for bank loan rejection and high monthly repayment obligations would also help syndicates to devise more sophisticated social engineering schemes to persuade individuals to take on non-legitimate bank loans, with the intention to exploit these individuals and get them to pay exorbitant interest rates.

Figure 7: Chinese threat actor selling PII of Chinese citizens with credit issues; the data contains full names, identification numbers, mobile phone numbers, cities where the bank operates, and reason for rejection of bank loans. We believe that the data might have been stolen by a credit bureau agency in China. ID card numbers, phone numbers, and full names have been censored. (Source: Exchange Market)

Figure 8: SMS records being stolen from Chinese installment provider Fenqile (Source: Exchange Market)

Fraudulent Chinese Lending Apps Targeting Indian Nationals and Connections to the Dark Web

In August 2022, the CIO of Economic Times reported that Chinese digital loan apps were utilizing a loophole in regulatory guidelines to dupe Indian clients by partnering with existing non-banking financial companies (NBFC). As these “fintech” companies were unlikely to get fresh NBFC licenses from the Reserve Bank of India, Chinese digital loan companies colluded with existing NBFCs to indulge in large-scale lending activities. Indian authorities found that various fintech companies in collusion with NBFC have indulged in predatory lending, charged exorbitant interest rates, imposed harsh penalties for late payment, operated illegally, and employed heavy-handed collection strategies. These Chinese apps would seek permission to access the victims’ contacts, which were later used for all sorts of blackmail by the company. Borrowers were charged exorbitant processing fees and interest rates, pushing many individuals into heavy debt and even causing some victims to commit suicide.

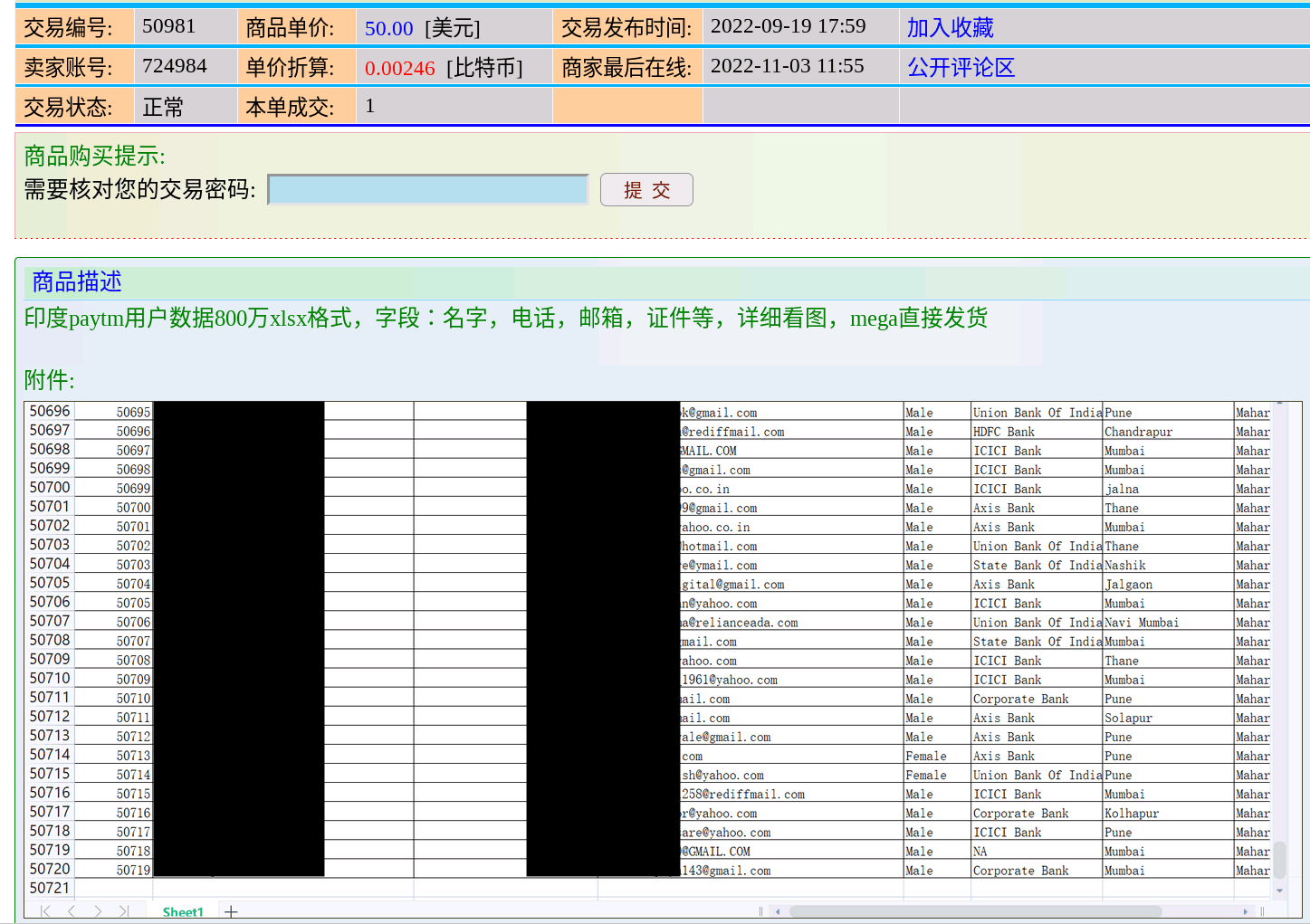

Recorded Future analysts discovered evidence that Chinese threat actors have targeted and stolen PII belonging to customers belonging to Paytm, an Indian digital payments and financial services company. The records of Indian nationals could be sold to the fraudulent Chinese digital loan companies described above, who could make use of the data to reach out to individuals found in the database to offer them digital loans via phishing and smishing campaigns.

| Type of PII | Intelligence |

| PII of users belonging to Indian digital payment company Paytm | On September 19, 2022, 724984, a member of Exchange Market, listed a database with more than 8 million records of Paytm users for $50. Paytm is an Indian digital payments and financial services company. The sample screenshots shared by the threat actor include the following data fields: full names, phone numbers, email addresses, state information, gender information, and names of banks used to connect with the Paytm service. The credibility of 724984 is moderate: the threat actor has made more than 100 postings on the Exchange Market since early August 2022. |

Table 9: PII of users belonging to Indian digital payment company Paytm that would likely contribute to the devisement of loan scams targeting Indian nationals (Source: Recorded Future)

Figure 9: Sample data of Paytm users, full names, email addresses, and phone numbers (censored) (Source: Exchange Market)

Chinese Threat Actors Targeting Japanese Entities through Spearphishing

In August 2022, Infosecurity Magazine reported that Japanese credit card customers have been targeted with phishing attacks. Menlo Labs’s research team analyzed a phishing campaign with targeted MICARD and American Express users in Japan, and discovered that the threat actor in question was sending potential targets spoofed emails with links to fake web pages, using geofencing to ensure that only Japanese IP addresses could access its websites.

We uncovered evidence that Chinese threat actors on Exchange Market have sold phishing website source codes that primarily target Japanese entities. Threat actors have managed to create phishing toolkits that look like legitimate Japanese banking, e-commerce, and transportation websites.

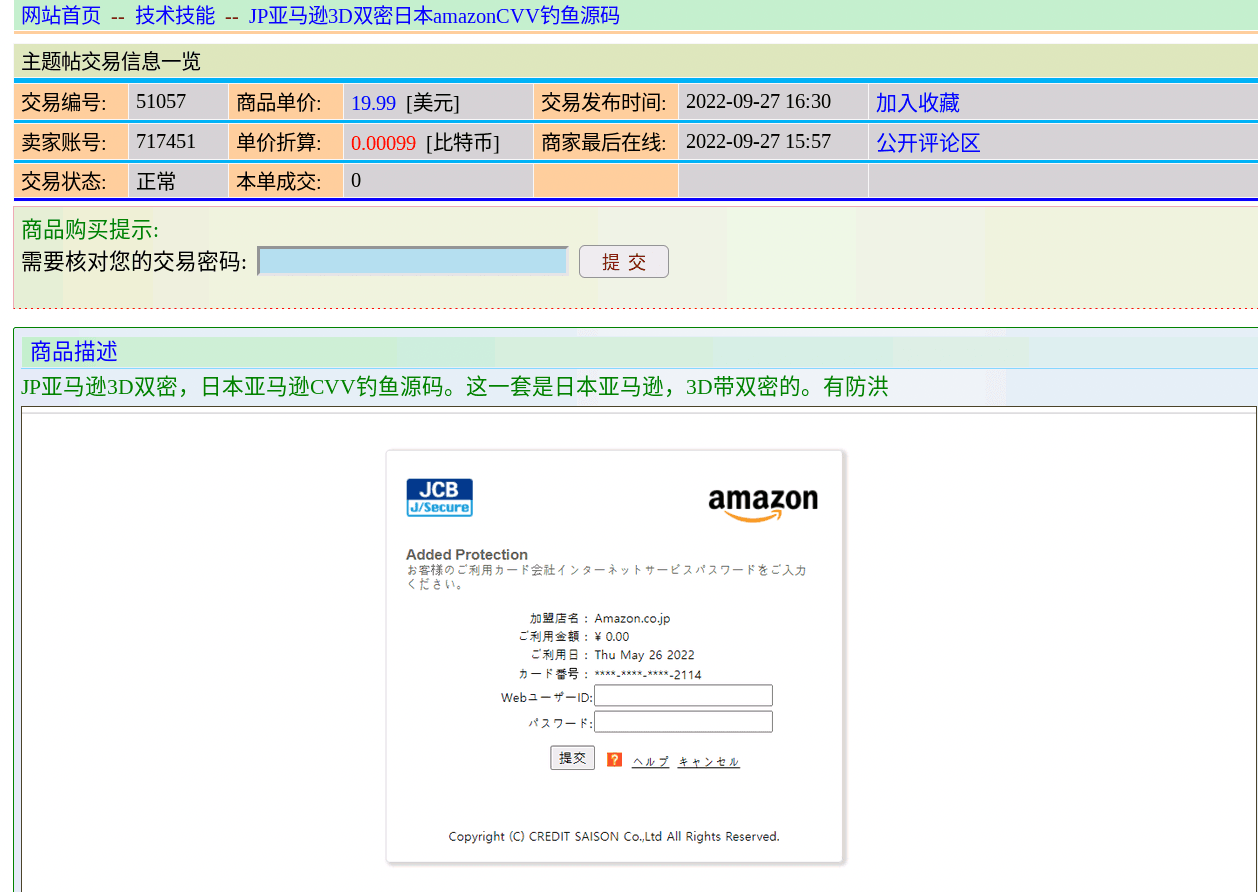

717451, a member of Exchange Market, sold phishing website source codes with the capability to steal login credentials and card verification values (CVVs). The threat actor listed Netflix, Apple UK, and Orient Corporation’s phishing kits for $20; Amazon Japan’s website phishing kits for $50; and Ekinet’s phishing kits for $10. The credibility of 717451 is low: the threat actor has made 5 postings since joining the Exchange Market in September 2022.

We believe that the threat actors who created these phishing kits have a good understanding of the Japanese language, culture, banking, e-commerce, and transportation system, which gives rise to the possibility that the threat actors could be Chinese nationals residing within Japan. We expect threat actors to continue to build more phishing kits to expand their spearphishing attack capabilities to target other Japanese industries, and that similar tactics can be replicated to target other foreign entities.

Figure 10: Phishing kit meant to steal login credentials and CVVs from Amazon Japan users (Source: Exchange Market)

China Official Impersonation Scam

In September 2022, AsiaOne reported that from January to August 2022, a total of 476 scams involving the impersonation of Chinese officials were reported in Singapore, with losses amounting to at least $57.3 million Singapore dollars. Chinese-speaking threat actors would typically call Chinese citizens living outside of China, often posing as law enforcement officers. The scammers would accuse the victims of having committed crimes and would often threaten them with jail terms. They would then usually persuade the victims to pay money to help to “avoid” investigations and jail sentences.

In the case study cited in the AsiaOne article, the scammer called a 16-year-old Chinese national living in Singapore and accused him of spreading COVID-19 rumors in China and of being involved in smuggling offenses. When the victim refuted the accusations, the caller told the victim that his mother might have given his personal data to malicious actors who committed those crimes using his identity, and that the mainland Chinese police would call him shortly after for further investigations. When the fictitious Chinese police called the victim, the scam caller told the victim that his mother was involved in money laundering and was asked to stage a hostage situation to convince her to confess. The victim eventually gave in, filmed himself as a hostage, and sent the video to his mother for ransom payment in exchange for the victim’s safe return to China.

Another similar case occurred in October 2022 that involved a Hong Kong university professor who was swindled out of nearly HK$4 million. In this case, the scammer accused the victim of flouting COVID-19 quarantine rules overseen by the Guangzhou Public Security Bureau and of being involved in a money laundering case in mainland China, which required him to submit personal particulars, including his Bank of China account details, to the scam syndicate to prove his innocence. The fictitious investigators successfully used fear and extortion tactics to transfer a total of HK $3.84 million over the course of 3 months.

We believe that these types of scams may work due to the large amount of PII data being sold that sometimes contains the PII of both students and their parents, along with data sets for Chinese nationals living abroad. The table below illustrates some examples of PII being sold on Exchange Market that might have helped syndicates to target overseas Chinese citizens for monetary gain.

| Type of PII | Intelligence |

| Students and Parents | On September 9, 2022, “649795”, a member of Exchange Market, sold a database with more than 1 million records of parents and junior high school students belonging to mainland China for $650. The threat actor claims that the list contains the information of students currently attending junior high school. The sample screenshots shared by the threat actor include the following data fields: full names of parents, full names of corresponding students, phone numbers, schools that the students are attending, classes, and levels that the students are attending. |

| Affluent Chinese Nationals Living in the US | On April 4, 2022, “628546”, a member of Exchange Market, sold 15,000 records of affluent Chinese citizens living in the US for $500. The sample screenshots shared by the threat actor include the following data fields: full names in Chinese, US phone numbers, gender information, marital status, province of origin in China, partial residency information containing US states and cities, occupation information, and date of immigration. |

| Overseas Chinese Citizens Living in Japan | On May 8, 2022, “567285”, a member of Exchange Market, sold 4,000 records of Chinese citizens residing in Japan for $640. The sample screenshots shared by the threat actor include the following data fields: full names in Chinese, Japanese phone numbers, gender information, partial residency information containing Japanese states and cities, marital status, and occupation information. |

| Nucleic Acid Results of Residents Living in China | On September 5, 2022, “737723”, a member of Exchange Market, sold a database with more than 5 million records of Chinese citizens related to nucleic acid test results (which can be used to identify past COVID-19 infections) for $145. The threat actor did not disclose the time period of the nucleic acid tests and did not specify any specific province or town where the nucleic tests were conducted; some data fields are incomplete. The sample screenshots shared by the threat actor include the following data fields: full names, nationalities, phone numbers, identity card numbers, and health code colors. |

Table 10: Types of PII that would have likely contributed to the devisement of scams targeting Chinese nationals beyond China’s national borders (Source: Recorded Future)

In September 2022, Nikkei Asia reported that Chinese scammers had made use of equipment that can interrupt and tamper with telecom signals, enabling them to alter their caller IDs so that victims believe they are receiving calls from official numbers. Bulk messaging software is also used to send text messages masked as notices. According to a report published by Madrid-based rights group Safeguard Defenders, China has forced nearly 10,000 Chinese living overseas suspected of corruption and financial crimes to return through covert and often illegal means including intimidation, threats, and even state-sanctioned kidnappings. According to a September 2022 report by Safeguard Defenders, the Chinese government has established at least 54 police-run “overseas police service centers” across 30 different countries, including the US, which have issued government documents stating that relatives in China that do not help police "persuade" targets to return to China should be investigated and punished by the police.

Recorded Future believes that victims who fall prey to such sophisticated phishing, smishing, or vishing scams are genuinely afraid of Chinese law enforcement forcibly repatriating them back to China for alleged financial crimes. A 2015 Forbes article claims that bribery is often an unspoken rule in China, where many companies pay bribes or give gifts in order to operate. It is also widely known in China, as seen in a March 2021 article by NPR, that it is possible to “pay your way out”, which refers to bribing Chinese officials to help individuals avoid persecution or to lessen criminal charges. Chinese cybercriminals likely leveraged the threat of forced repatriation based on financial crimes, the bribing culture, and the compromised PII of Chinese nationals living overseas, in order to successfully impersonate Chinese law enforcement officials and scam victims. Scam phone calls are usually well planned and sophisticated; the scam caller usually knows significant details of the victims’ PII such as full names, ID card numbers, home addresses in China, overseas addresses, occupations, as well as information belonging to family members. Possession of these details helps the scam callers to instill fear in their victims and to convince victims to give in to the scammer’s demands, as it can be extremely hard for the overseas Chinese national to determine whether or not the call is from a legitimate Chinese authority.

Chinese nationals living overseas are often targeted due to the perception that they are generally affluent if they are able to live in First World countries such as the US, Singapore, Canada, Japan, Germany, and other countries that have a much higher cost of living than China. Many wealthy Chinese are already moving out of China to countries like Singapore due to China’s growing political rhetoric of “common prosperity” and “going after the entrepreneurs”, and also in response to severe COVID-19 lockdowns.

Crypto Romance Scams Targeting Women

In June 2022, the Financial Times reported that crypto swindlers preyed on ethnic Chinese women looking for love, in scams where fraudsters establish online romances before duping victims of their life savings. Fraudulent actors will usually create fake websites that mimic the names of real exchanges, such as “KrakenCoin” and “Coinbase CCY”. These websites have 24/7 online customer service and charts showing live coin price fluctuations, and would initially allow the unsuspecting women to withdraw some assets into fiat currency, duping them into trusting the platform. This type of scam is also known as a pig butchering scam, which affects both males and females.

In August 2022, the CAC ordered the removal of 12,000 crypto-related websites and social media accounts for promoting cryptocurrencies. Social media accounts from multiple platforms including Weibo, Baidu, and WeChat were shut down, along with 105 websites that promoted and ran tutorials on buying, selling, and mining digital assets. The Financial Regulatory Bureau of Shenzhen warned in June 2022 that cryptocurrency bred criminal activities and disrupted financial order, and cautioned investors against participating in illegal financial activities and potentially being scammed.

We found evidence on the Chinese dark web that threat actors have listings that contain records of PII belonging to females; cryptocurrency scammers could exploit this data and devise scam tactics and strategies to use against the women whose PII have been compromised.

| Type of PII | Intelligence |

| Female Data from Dating Site | On May 11, 2022, “565231”, a member of Exchange Market, advertised 7,000 records of PII from female users of the Chinese dating website zhenai[.]com for $700. The data field of the screenshot shared by the threat actor includes customer names, cell phone numbers and carriers, dates of birth, genders, personal ID numbers, physical addresses, employers, and places of birth. |

| Chinese Female College Students | On September 17, 2022, “751891”, a member of Exchange Market, listed a database with more than 2.4 million records of Chinese female college students based in Guangdong for $300. The threat actor claims that the data was newly obtained in August 2022, with most students being in the age range of 19 to 25 years old based on data collected from 140 colleges in the Guangdong province. The sample screenshots shared by the threat actor include the following data fields: full names, genders, identity card numbers belonging to students and guardians, birth dates, marital statuses, ethnicities, phone numbers, email addresses, employment statuses, hometown information, contact addresses, and personal information belonging to the guardians of the students. |

Table 11: Types of PII that would have likely contributed to the devisement of crypto romance scams targeting women (Source: Recorded Future)

Outlook

On October 23, 2022, President Xi Jinping secured a third term as the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC) at the 20th National Congress, further consolidating his power. President Xi’s speech to party cadres suggests that he intends to firmly implement the zero-COVID policy, which has already seen negative economic and social costs. With increasing economic hardship and high levels of youth unemployment (close to 20%), China is currently seeing a growing trend of online scams, particularly tens of thousands of counterfeit financial services applications meant to dupe consumers for financial gain, and will continue to clamp down on these activities and criminal gangs with tougher new legislations. The slowing economic growth and widespread discontent will likely drive disenfranchised youth into cybercrime due to lack of economic opportunities. We also expect the majority of lower-level Chinese threat actors to continue to conduct cyberattacks against China’s domestic industries including healthcare, financial, government, and education entities for financial gain. More resourceful threat actors will move their cyber operations abroad or focus more on foreign data/access to diversity their portfolio, recruiting foreign cybercriminals to participate in cyberattacks against global entities.

Despite the heated rhetoric and warnings, no large-scale cyberattacks took place during US Speaker Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan. There were only low-level DDoS attacks likely attributed to patriot hacktivism. However, President Xi vowed to never renounce the use of military force to take control of Taiwan, which will inevitably cause greater tensions with the US and with Taiwan. Although China denied the existence of any timeline for reunification with Taiwan, the recent reshuffling of military leadership clearly indicated a focus on Taiwan in the next 5 years and beyond. However, Russia’s lack of military success in the invasion of Ukraine, coupled with the near-unanimous international condemnations and sanctions following the invasion, will serve as a warning to China should it consider conducting a military invasion of Taiwan. We believe that a large-scale military conflict is unlikely to take place, but that cyber warfare is likely, involving the deployment of China’s cyberwarfare units and the possible assistance of Russian and North Korean threat actors in targeting, disrupting, or destroying entities deemed vital to the US and its allies, primarily with regard to the semiconductor industry.

On October 28, 2022, China’s State Council announced that China will construct a national integrated government big data system. Data available to the government will also be expanded to include information on electronic licenses, medical and healthcare, emergency management, and credit systems, and to incorporate them into the national integrated government affairs big data system. An integrated big data system can be considered a gold mine in the eyes of cybercriminals, and we expect threat actors to attempt to breach the new big data system as well as to target other state organs that hold sensitive data, and to use data-fusion pools to analyze and break down the data sets into smaller data sets that could be weaponized against individuals. These smaller data sets are highly likely to contain information that appeal to criminal gangs, such as those involved in illegal lending practices as well as syndicates that conduct scams by impersonation of government officials.

We also believe that some Chinese companies might purchase data sets containing criminal records as a form of background check before hiring individuals. There is also the possibility of Chinese citizens with past criminal records having their data compiled and posted on websites for people interested in doing open-source background checks, which will affect the socio-economic outlook of these individuals. There is also the possibility of threat actors manipulating the data of ex-offenders by tweaking records found in breached data sets, which can result in negative consequences such as having people with no past criminal records being included in data sets containing records of ex-offenders, which will affect their chances of getting hired.

The Chinese government’s push for an integrated system for their political and economic objectives will likely come with negative consequences, allowing the cybercriminal landscape to evolve and thrive with more threat actors devising new and innovative methods to weaponize or even manipulate PII to serve the needs of other criminal gangs and organizations in the event of future data breaches.

Related