North Korea Targeted South Korean Cryptocurrency Users and Exchange in Late 2017 Campaign

Key Judgements

- North Korean government actors, specifically Lazarus Group, continued to target South Korean cryptocurrency exchanges and users in late 2017, before Kim Jong Un’s New Year’s speech and subsequent North-South dialogue.

- This campaign also targeted South Korean college students interested in foreign affairs and part of a group called “Friends of MOFA” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs).

- The malware employed shared code with Destover malware, which was used against Sony Pictures Entertainment in 2014 and the first WannaCry victim in February 2017.

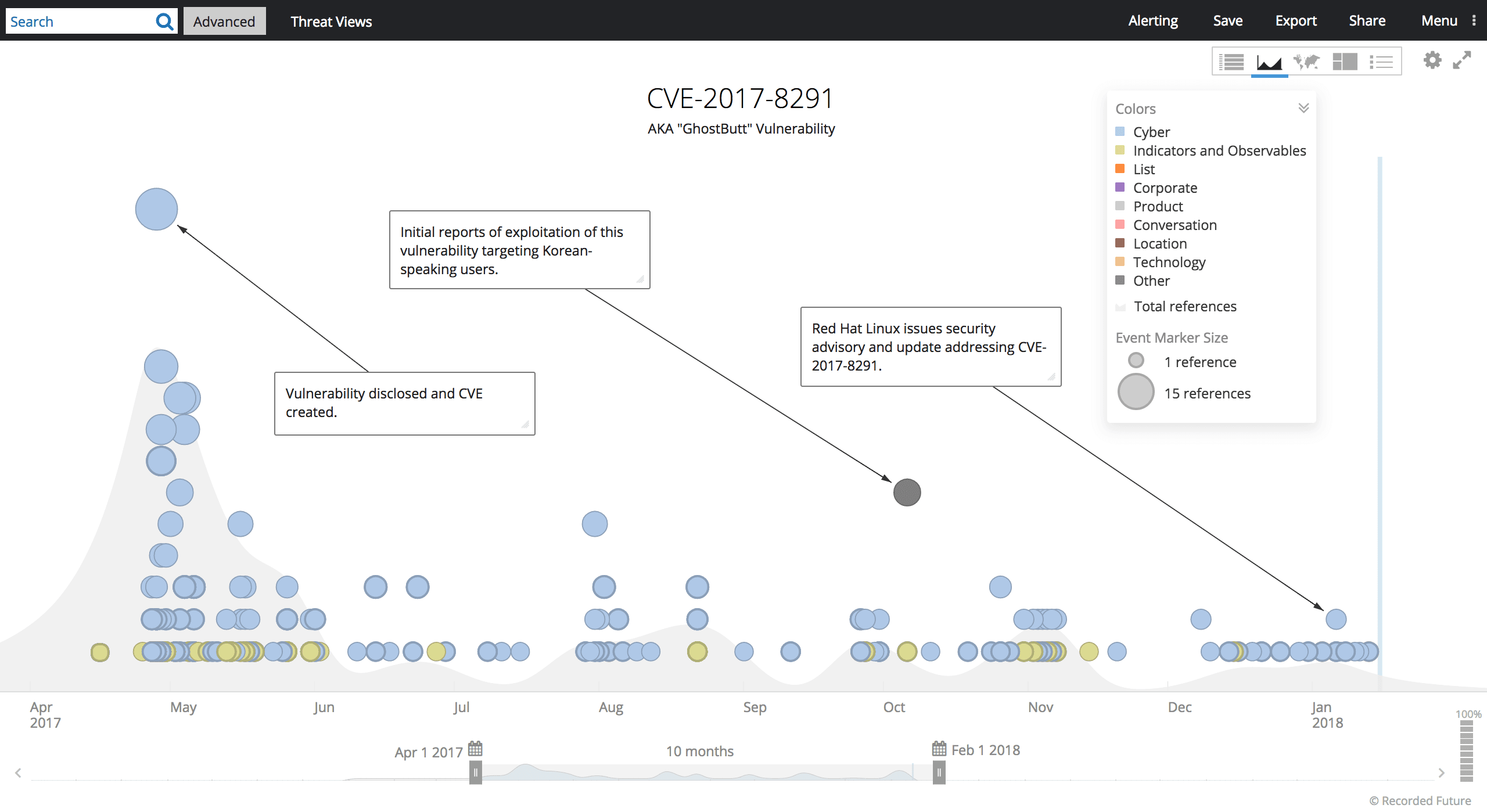

- The dropper in this campaign exploited a known Ghostscript vulnerability, CVE-2017-8291. The exploit implementation includes Chinese terms possibly signifying an attempted false flag or a Chinese exploit supplier.

Executive Summary

North Korea continued to target South Korea through late 2017 with a spear phishing campaign against both cryptocurrency users and exchanges, as well as South Korean college students interested in foreign affairs. The malware in this campaign utilizes a known Ghostscript exploit (CVE-2017-8291) and is tailored to target only users of a Korean language word processor, Hancom’s Hangul Word Processor.

Background

North Korean state-sponsored cyber operations are largely clustered within the Lazarus Group umbrella. Also known as HIDDEN COBRA by the U.S. government, Lazarus Group has conducted operations since at least 2009, when they launched a DDoS attack on U.S. and South Korean websites utilizing the MYDOOM worm. Until 2015, Lazarus Group cyber activities primarily focused on South Korean and U.S. governments and financial organizations, including destructive attacks on South Korean banking and media sectors in 2013 and the highly publicized attack on Sony Pictures Entertainment in 2014.

Beginning in 2016, researchers discovered a shift in North Korean operations toward attacks against financial institutions designed to steal money and generate funds for the Kim regime.

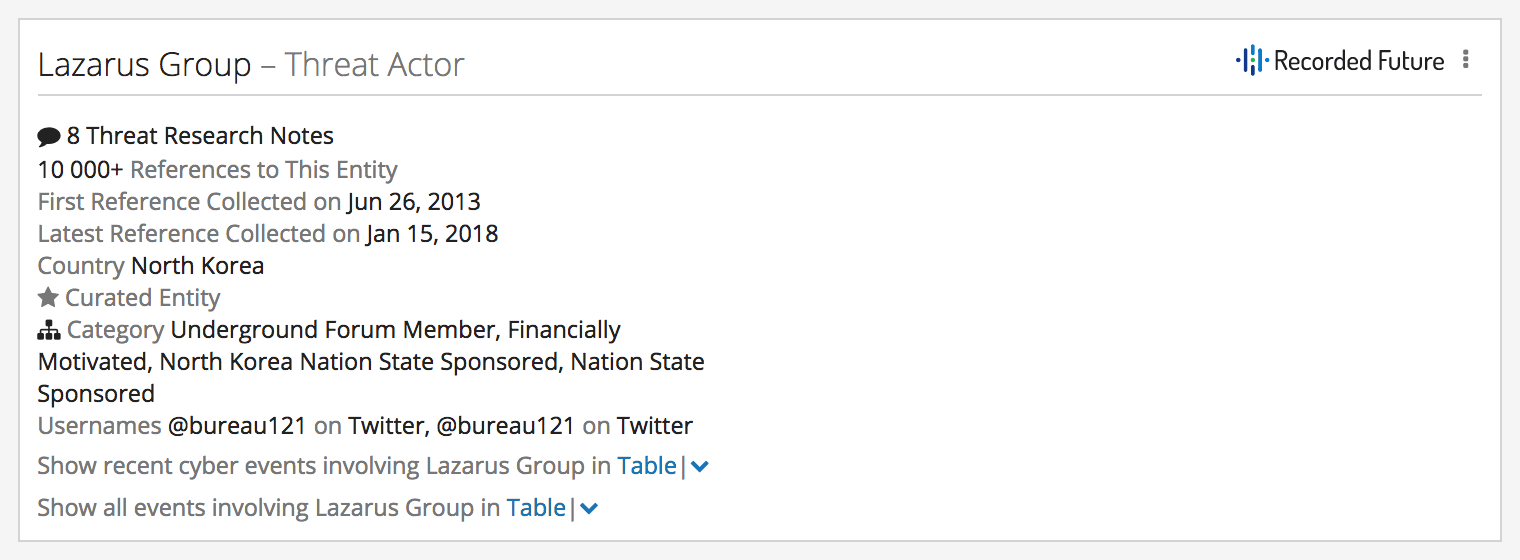

Lazarus Group in Recorded Future.

By 2017, North Korean actors had jumped on the cryptocurrency bandwagon. The first known North Korean cryptocurrency operation occurred in February 2017, with the theft of $7 million (at the time) in cryptocurrency from South Korean exchange Bithumb. By the end of 2017, several researchers had reported additional spear phishing campaigns against South Korean cryptocurrency exchanges, numerous successful thefts, and even Bitcoin and Monero mining. North Korea also utilized Bitcoin for the global WannaCry ransomware attack in mid-May, forcing victims to pay ransom in Bitcoin.

Threat Analysis

Insikt Group researchers regularly follow North Korean threat actors through a variety of methods, one of which includes proactive monitoring of attack vectors based on software disproportionately adopted in South Korea. Using this methodology, we identified a recent Lazarus Group malware campaign, which likely began late Fall 2017. Lazarus Group operations target a wide swath of countries and verticals, with a particular interest in South Korean targets.

Recent reporting regarding North Korean attacks against cryptocurrency exchanges and using Pyeongchang Olympics as a lure describe techniques that are unusual for the Lazarus Group. These include leveraging PowerShell, HTA, JavaScript, and Python, none of which are common in Lazarus operations over the last eight years. The campaign we discovered showcases a clear use of Lazarus TTPs to target cryptocurrency exchanges and social institutions in South Korea.

This campaign leveraged four different lures and targeted Korean-speaking users of the Hangul Word Processor (.hwp file extension), a Korean-language word processing program utilized widely in South Korea. North Korean state-sponsored actors have used Hangul exploits (CVE-2015-6585) and malicious .hwp files in the past, including during a phishing campaign in early 2017, to target South Korean users. Beyond Korean-speaking HWP users, targets of this campaign appear to be users of the Coinlink cryptocurrency exchange, South Korean cryptocurrency exchanges at large (or at least those that are hiring), and a group called “Friends of MOFA” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs), which is a group of college students from around South Korea with “a keen interest in foreign affairs.”

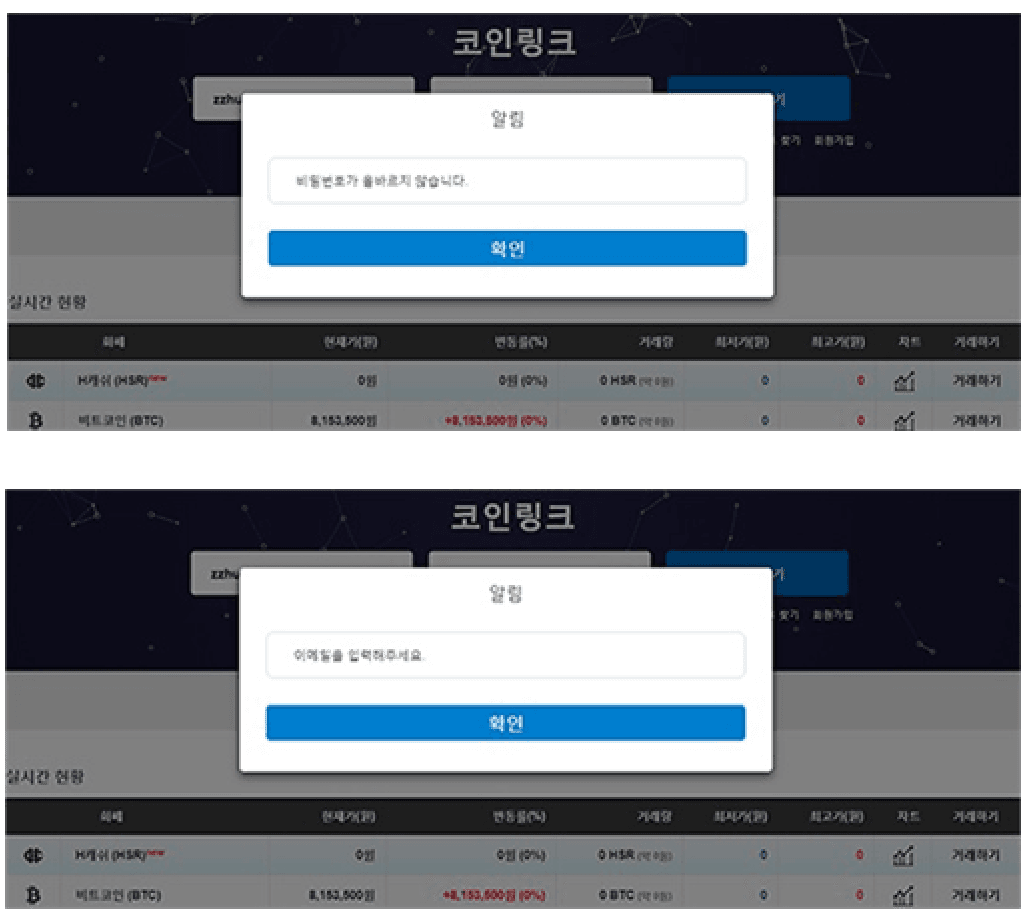

Payload shows two prompts from coinlink.co.kr, the first tells the user their password is incorrect, the second asks for their email address.

The first cryptocurrency-focused lure appears designed to obtain the emails and passwords of users of Coinlink, a South Korean cryptocurrency exchange.

The second and third appear to be resumes stolen from two actual South Korean computer scientists, both with work experience at South Korean cryptocurrency exchanges.

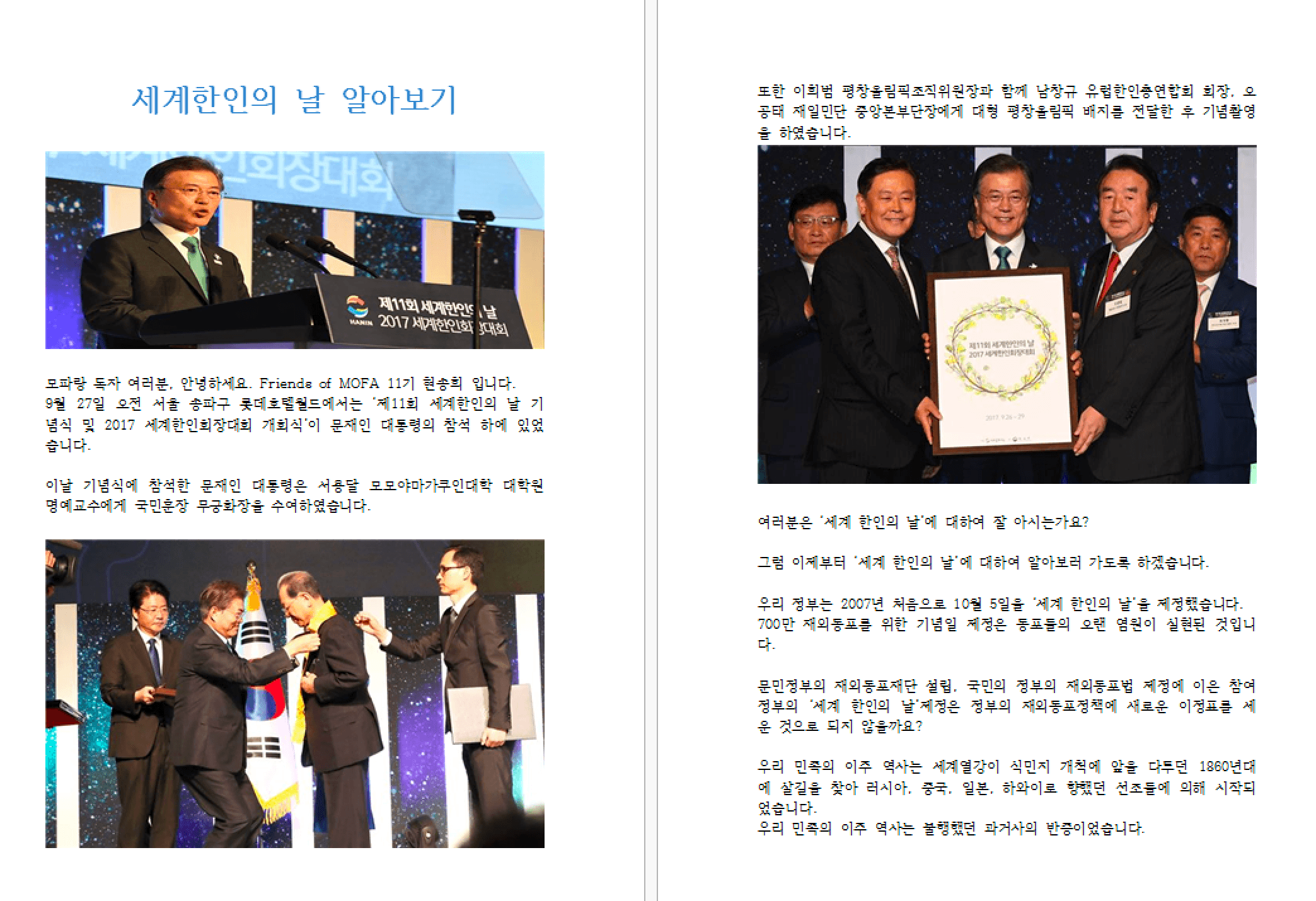

The fourth document was lifted from a blog run by the South Korean group “Friends of MOFA” detailing a Korean Day celebration in late September 2017 during which President Moon Jae-in spoke about the importance of the Korean diaspora and the upcoming Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang.

This document is from a blog post from the “Friends of MOFA” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) detailing a Korean Day celebration attended by President Moon Jae-in.1

Technical Analysis

This campaign relies on a known Ghostscript exploit (CVE-2017-8291) that can be triggered from within an embedded PostScript in a Hangul Word Processor document.

Timeline of CVE-2017-8291 exploitation.

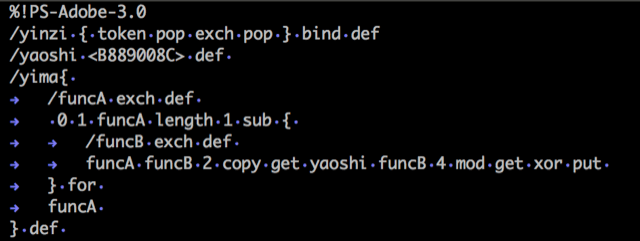

Screenshot of the function names utilized in the PostScript.

Our initial finding focused on “로그인 오류.hwp“ or “Korean Day” lure, but once we created a signature for the particular implementation of the PostScript, we found three additional lure documents in a public malware repository tied together by the use of this exploit: two CVs and a cryptocurrency exchange-themed lure. All were created in the span of a month from mid-October to late November. Despite a nearly identical delivery mechanism (with the exception of altered 4-byte XOR keys), the payloads (when recoverable) were different in each case.

It’s worth noting that the function names used in the PostScript are transliterated Chinese words. While “yima” (decode) and “yaoshi” (key) appear appropriate in their functional context, the word “yinzi” (factor/money) does not. The latter may be obscure technical slang or be a misuse signifying a potential false flag.

This would not be the first time the Lazarus Group used foreign-language terms to misdirect attribution efforts; BAE researchers discovered transliterated Russian terms in previous Lazarus operations. However, an alternate explanation may point to a Chinese exploit supplier or the language competency of the developer.

The attack chain occurs in multiple stages with the PostScript deobfuscating a first stage shellcode that’s been XORed with a hardcoded four-byte key. The shellcode in turn triggers the GhostScript vulnerability in order to execute an embedded DLL that has also been XORed. A PwnCode.Club blogpost details the deobfuscation of the shellcode and loading of the DLL into memory.

Lazarus malware families (like Hangman, Duuzer, Volgmer, SpaSpe, etc.) overlap, likely as the result of the developers cutting-and-splicing an extensive codebase of malicious functionality to generate payloads as needed. This erratic composition make the Lazarus intrusion malware difficult to identify and group or cluster, unless they are analyzed at the level of code similarity.

Upon deobfuscating the payloads, we found 32-bit DLLs built in part on the Destover malware code. Destover has been used in a number of North Korea-attributed operations: most infamously against Sony Pictures Entertainment in 2014, the Polish banking attacks in January 2017, and the first WannaCry victim in February 2017.

This campaign relies on multiple payloads fashioned out of the Destover infostealer code to collect information about the victim system and exfiltrate files. Each payload contains an embedded 64-bit version of itself. The payloads accompanying the newer cryptocurrency exchange-themed lure docs compiled a month after the Korean Day payload further obfuscate their functionality by resolving imports at runtime.

This type of obfuscation is common in the Lazarus Hangman malware family. They also rely entirely on IPs (rather than domains) for their command-and-control infrastructure, a tactic likely borne of the use of hacked servers for infrastructure.

Outlook

This late 2017 campaign is a continuation of North Korea’s interest in cryptocurrency, which we now know encompasses a broad range of activities including mining, ransomware, and outright theft. Outside of the May WannaCry attack, the majority of North Korean cryptocurrency operations have targeted South Korean users and exchanges, but we expect this trend to change in 2018. We assess that as South Korea responds to these attempted thefts by increasing security (and possibly banning cryptocurrency trading) they will become harder targets, forcing North Korean actors to look to exchanges and users in other countries as well.

Further, while this campaign and toolset are specific to the Hangul Word Processor, the vulnerability it exploited (CVE-2017-8291) is not. This vulnerability is for the Ghostscript suite and affects a wide range of products, and while this particular version is triggered from within an embedded PostScript in an HWP document, it could easily be adapted to other software.

As South Korean exchanges harden their networks and the government imposes stricter regulatory controls on cryptocurrencies, exchanges and users in other countries should be aware of the increased threat level from North Korean actors.

Related