Dark Covenant 2.0: Cybercrime, the Russian State, and the War in Ukraine

Editor’s Note: This is an excerpt of a full report. To read the entire analysis with endnotes, click here to download the report as a PDF.

This report examines the unspoken connections between the Russian Federation, cybercriminals, and self-described hacktivists in Russia and Eastern Europe in the context of the Russian war in Ukraine. It is a direct continuation of the findings presented in our 2021 report “Dark Covenant: Connections Between the Russian State and Criminal Actors”. This report will be of interest to threat researchers, as well as law enforcement, government, and defense organizations.

Executive Summary

Beginning on February 24, 2022, the Russian cybercriminal threat landscape underwent transformative changes in response to the Russian war in Ukraine. The war brought chaos to the cybercriminal underground, polarizing threat actors in Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) nations. While some cybercriminal groups declared allegiance to the Russian government, others splintered over irreconcilable ideological differences or remained apolitical, opting to capitalize on geopolitical instability for financial gain. Some groups vanished entirely. Likely as indirect consequences of the war, there have been underground market disruptions, shifts in hacktivist and ransomware targeting, and a spike in financial fraud, among other phenomena affecting the Russian cybercriminal ecosystem.

Throughout these changes, one thing remained largely constant: cybercriminal threat groups continue to occupy important roles — in direct, indirect, and tacit capacities — with the Russian government. For cybercrime groups who have pledged their allegiance to the Kremlin, the unspoken connections have deepened. Russian cybercriminals and self-described hacktivists are actively involved in operations targeting Ukrainian entities and infrastructure, as well as entities located in states that have declared their support for Ukraine. Recorded Future has observed Russian and Russian-speaking threat actors targeting the United States, United Kingdom, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), Japan, and others for financial gain and ego-driven publicity in support of Russia.

Figure 1: Conti Gang statement dated February 25, 2022, in which the group allies itself with the Russian government (Source: Conti.News)

Figure 1: Conti Gang statement dated February 25, 2022, in which the group allies itself with the Russian government (Source: Conti.News)

Cybercriminal organizations like Conti have overtly declared allegiance to the Russian government, and commodity malware like DarkCrystal RAT, Colibri Loader, and WarZoneRAT, which are available on top-tier Russian-language forums, are being used by advanced persistent threat (APT) groups to target entities in Ukraine. We have identified cybercriminal activities preceding the war, and immediately after it started, that we believe are the work of the Russian state. Russian-speaking, self-described “hacktivist” groups like Killnet and Xaknet are almost certainly actively engaging in information operations (IOs) against organizations and entities in the West, enabled by Russian state-sponsored media with the likely intended goal of stoking fear or decreasing support for Ukraine. We have also identified other phenomena, such as a rise in payment card fraud, database leaks, dark web marketplace closures, and more, that we believe are the consequences of economic, diplomatic, and law enforcement activities aimed at Russian entities due to their support for the war in Ukraine.

Key Judgments

- It remains highly likely that Russian intelligence, military, and law enforcement services have a longstanding, tacit understanding with cybercriminal threat actors; in some cases, it is almost certain that these agencies maintain an established and systematic relationship with cybercriminal threat actors, either by indirect collaboration or via recruitment.

- Based on our understanding of cybercriminal and hacktivist activities related to the Russian war in Ukraine, it is likely that cybercriminal threat actors are working alongside the Russian state to coordinate or amplify Russian offensive cyber and information operations.

- Russian cybercriminal groups, tools, and tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) likely serve to provide plausible deniability for state-sponsored threat actors involved in the Russian war in Ukraine. It is likely that financially motivated threat actors who are capitalizing on geopolitical instability are also aiding and abetting the interests of the Russian state, be it coincidentally or intentionally.

- Russian law enforcement seizures of dark web and special-access sources preceding the war appeared to be a show of good faith by the Russian state, signaling its willingness and ability to thwart cybercrime. However, we believe it is likely that these enforcement actions were intended to undermine allegations of cooperation between cybercriminals and the Russian state, providing further plausible deniability.

- Several cybercriminal industries have undergone transformational changes as a result of the Russian war in Ukraine. These include changes to the malware-as-a-service (MaaS) and ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) threat landscapes, a rise in Russian payment card fraud, shifts in cybercriminal targeting, changes in infrastructure and hosting, and more.

Methodology

This report synthesizes information derived from open and human sources, including information gathered from monitoring of, and engagement on, dark web, special-access, and social media sources frequented by Russian-speaking cybercriminals. We looked at several English-language forums to cross-reference points of contact and link monikers suspected to be operated by Russian-speaking cybercriminals across the dark web. We also gathered intelligence from open and closed-source messaging platforms, such as Telegram, Tox, and Jabber (XMPP), as well as social media.

Our collections on ransomware extortion, chat, and payment websites helped us connect various ransomware groups with the Russian state. We used qualitative and quantitative methods to study ransomware victimology before and after the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, to theorize about motives and ideology. This report relies heavily on the use of the Recorded Future Platform® to visualize its findings and draw connections between geopolitical events, cybercriminal threat actors and threat actor groups, advanced persistent threats (APTs), and the Russian state in the context of the Russian war in Ukraine.

We also rely heavily on other forms of OSINT research, such as academic publications, industry white papers, conference presentations, and more, to fill in gaps in our HUMINT collections process. This report uses previous open-source reporting, as well as the original 2021 Dark Covenant report, as the background and warrant for its research. This report was researched and written between February 24, 2022 and August 24, 2022.

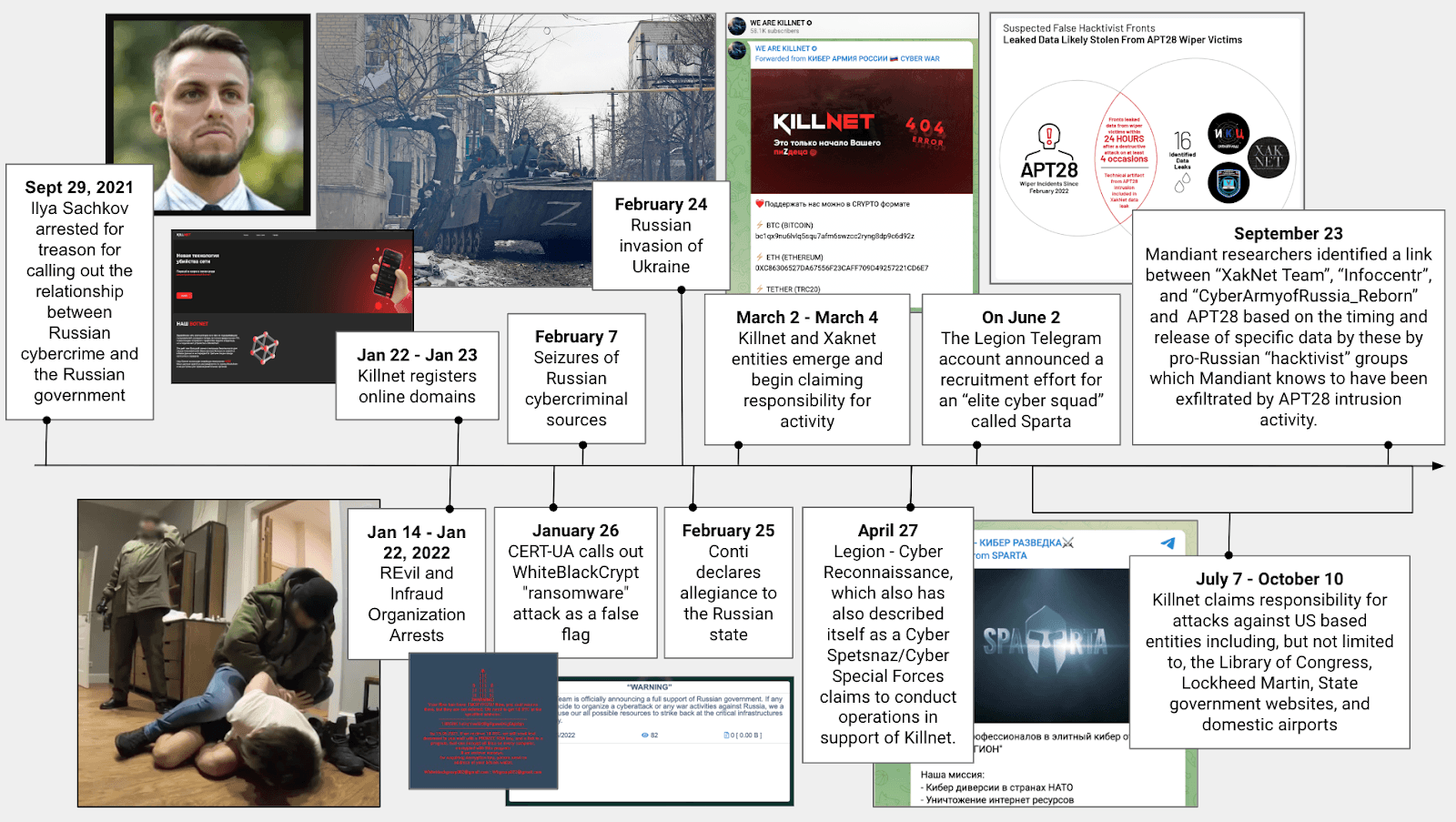

Figure 2: Timeline of events between the cybercriminal ecosystem, self-described hacktivist entities, and state-sponsored groups during the conflict in Ukraine (Source: Recorded Future)

Figure 2: Timeline of events between the cybercriminal ecosystem, self-described hacktivist entities, and state-sponsored groups during the conflict in Ukraine (Source: Recorded Future)

Background

“Dark Covenant”

In 2021, we detailed how established, distributed networks of individuals in the Russian cybercriminal world and officials in Russian law enforcement or intelligence services — also known colloquially as siloviki — are connected. The report detailed how the relationships in this ecosystem are often premised on unspoken, yet understood, agreements that consist of malleable associations. This research was based on historical activity, public indictments, and ransomware attacks. Overall, the report broke down the associations between the Russian cybercriminal environment and the siloviki into 3 major categories: direct associations, indirect affiliations, and tacit agreements.

- Direct associations are identified by precise links between state institutions and criminal underground operators; an example of this is Dmitry Dokuchaev, a major in the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) who was recruited after working as a cybercriminal.

- Indirect affiliations occur in cases where a direct link cannot be established but there are clear indications that the Russian government is using resources or personnel for its benefit; an example of this is the Russian government’s likely use of the GameOver Zeus botnet for espionage or DDoS attacks by “patriotic hackers” during military conflicts.

- Tacit agreement is defined as overlaps in cybercriminal activity, including targeting and timing, that benefit Russian state interests or strategic goals; such activity is conducted without direct or indirect links to the state but is allowed by the Kremlin, which looks the other way when such activity is conducted.

In our 2021 report, we assessed that cybercriminal associations with the siloviki would almost certainly continue for the foreseeable future and these associations and activities would likely adapt to provide greater plausible deniability and fewer overt, direct links between both groups.

Since our first report, the Russian government has invaded Ukraine, an event that has illuminated our understanding of Russia’s capabilities and shortcomings as they relate to military strength and cyber capacity. For example, a series of leaks about the cybercriminal groups Conti and Trickbot (Wizard Spider) provided an unprecedented look at the relationship between these groups and the state. The conflict has given rise to self-described hacktivists conducting pro-Russian attacks purportedly motivated by patriotic interest; in some cases, however, it is likely that such groups are providing the Russian government with plausible deniability.

The Russian Invasion of Ukraine

The February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine has resulted in a broader humanitarian crisis in Europe as well as heightened international tensions. A number of pro-Russian threat actor groups, as well as some previously unseen entities from within the cybercriminal ecosystem, have participated in the conflict, which Russia has conducted across the physical, information, and cyber domains. The war has already seen large-scale distributed denial-of-service attacks (DDoS), website defacements, phishing and spam campaigns, malware deployment, and wiper attacks against numerous Ukrainian entities in both the government and private sector.

Russian Cybercrime in Cyber Warfare

The Russian intelligence services’ recruitment of highly skilled computer programmers, network specialists, and other technologically savvy personnel dates back to at least the 1990s, according to a Meduza report published on December 12, 2019. In this report, an FSB officer is quoted as suggesting that as soon as hackers achieve a certain level of success, they are targeted for recruitment: “In [the FSB officer’s] words, as soon as ‘the first technical college student from a humble background brought a Ferrari out onto the streets of Moscow’, FSB agents started recruiting — both getting the cybercrime business under control and making it their own”.

In his 2019 book “Intrusion: A Brief History of Russian Hackers”, Daniil Turovsky quoted an unnamed Russian hacker who provided an account of the associations between the criminal underground and the Russian intelligence services. According to the hacker, the Center for Information Security at the Russian Federal Security Service (CIB FSB) had limited technical staff, so it often brought in outside specialists, reportedly going so far as to hide some hackers in safe houses.

Andrei Soldatov, a Russian investigative journalist and co-author of “The Red Web”, a book about the Kremlin’s online activities, said that while the Russian government’s tactic of outsourcing cyber operations to various groups helps distance themselves (and ultimately provides deniability), it also left them vulnerable to hackers running amok.

Russian Cybercrime in Foreign Policy

In September 2021, around the time we released our initial Dark Covenant report, we identified a shift in calculus following recent high-profile ransomware attacks and subsequent intergovernmental consultations between the US and Russia. At the time, high-profile ransomware attacks against Colonial Pipeline, JBS, and Kaseya led the US to increase pressure on the Russian government to take action against the cybercriminal groups behind this activity. Around this time, the administrators of 2 major Russian-language forums, Exploit and XSS, quickly banned ransomware topics on their criminal underground platforms, likely as a result of the increased pressure. However, ransomware activities persist in the form of “initial access” and “data leak” brokerage services. Moreover, the DarkSide, REvil, and Avaddon ransomware families halted extortionist activities right before or days after the first meeting between US president Joe Biden and Russian president Vladimir Putin on June 16, 2021, in Geneva, Switzerland. This pause was only temporary, as ransomware attacks continued in 2022, including attacks affecting critical infrastructure targets in the energy sector and transportation entities in Europe (1, 2, 3).

Related