Counterfeit Wine, Spirits, and Cheese

Counterfeit wine has been a problem for a long time. It has been a running joke in the wine industry for decades that more 1982 Petrus is sold in Las Vegas every year than was ever produced by the estate. However, fake wine is much older than that. While most people today know Pompeii as “the volcano place”, in its day, some of the most sought-after wines in the world came from that region, which is known as Campania. Archaeologists have unearthed evidence that there were merchants selling counterfeit Campania wine (PDF). Interestingly, similar to the way many counterfeiters work today, it appears that Campania wine counterfeiters would use what appear to be authentic Pompeian amphoras (with all of the proper stamps) but replace the wine with wine from other regions.

Counterfeit wine is estimated to be a $65 billion industry, and fake wines may account for as much as one-fifth of all wine sales. Similarly, a 2018 study found that more than one-third of bottles of Scottish whisky on the secondary market were forgeries. According to the Parmigiano Reggiano Cheese Consortium, the counterfeit Parmesan cheese counterfeit market was $2 billion — almost as much as the total sales for legitimate Parmesan cheese. Overall, counterfeit wine, spirits, and cheese are part of a $1.6 to $2.2 trillion market (2017) for counterfeit goods.

This report will look at:

- The scope of the counterfeit wine, cheese, and spirits market

- How fake products are produced and sold

- Steps that are being taken to foil counterfeit wine, spirits, and cheese

The Scope and Analysis of Counterfeit Products

Wine

In her 2015 book Thirsty Dragon: China’s Lust for Bordeaux and the Threat to the World’s Best Wines, Suzanne Mustacich writes:

There was also more 1998 Bordeaux in China than had ever been exported. The vintage wasn’t special — in fact, it was average in quality — but vintage didn’t mean anything to the Chinese. Even the bottles were poor quality. Bartman speculated that the counterfeiters were betting on the attraction of the number 8 as a symbol of wealth and the number 9 as a symbol of harmony.

Many consider counterfeit wine a problem that happens in countries like China, where counterfeit goods are common, or that it mostly affects wealthy people who buy bottles of wine worth tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars. But counterfeit wine affects a wide range of consumers — for example, in April of this year a wine shop in the United Kingdom (UK) was threatened with revocation of its alcohol license after it was found to be selling counterfeit bottles of Yellow Tail Shiraz, a wine that normally sells for $7 to $10 in the United States (Yellow Tail Shiraz retails for about £7 to £9 in the UK). Wine fraud is everywhere and it affects all types of winemakers and wine drinkers.

Scope of Wine Fraud

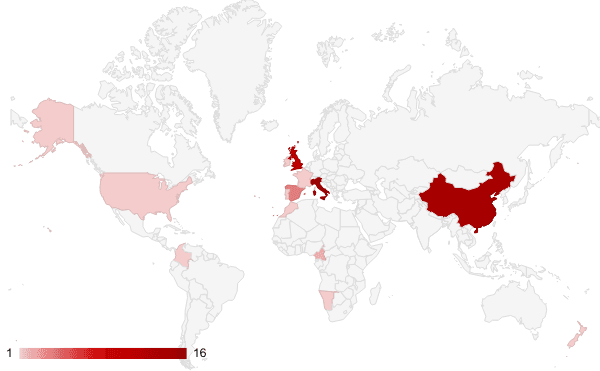

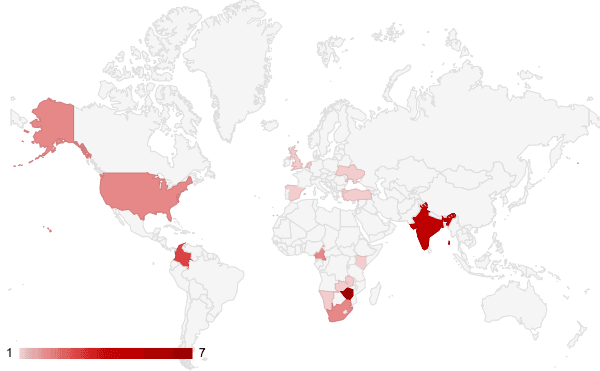

Figure 1: Scope of reported wine fraud around the world January 2020 to June 2022 (Source: Recorded Future)

Figure 1: Scope of reported wine fraud around the world January 2020 to June 2022 (Source: Recorded Future)

Measuring the scope of wine fraud is very challenging. Like cyber incidents, cases of wine fraud often go undetected or unreported. Even so, Recorded Future was able to capture dozens of publicly reported cases of wine fraud between January of 2020 and June of 2022 in countries around the world.

While there is, understandably, a lot of attention on China as a source of counterfeit wine, most of the publicly reported cases Recorded Future found occurred in Italy, which accounted for 16 publicly reported cases, versus 14 in China during that time period. That doesn’t necessarily mean that more counterfeit wine occurs in Italy than China; it is likely the case that there is simply a better investigative framework in Italy for detecting counterfeit wines and prosecuting those who attempt to pass off fake wine as the real thing.

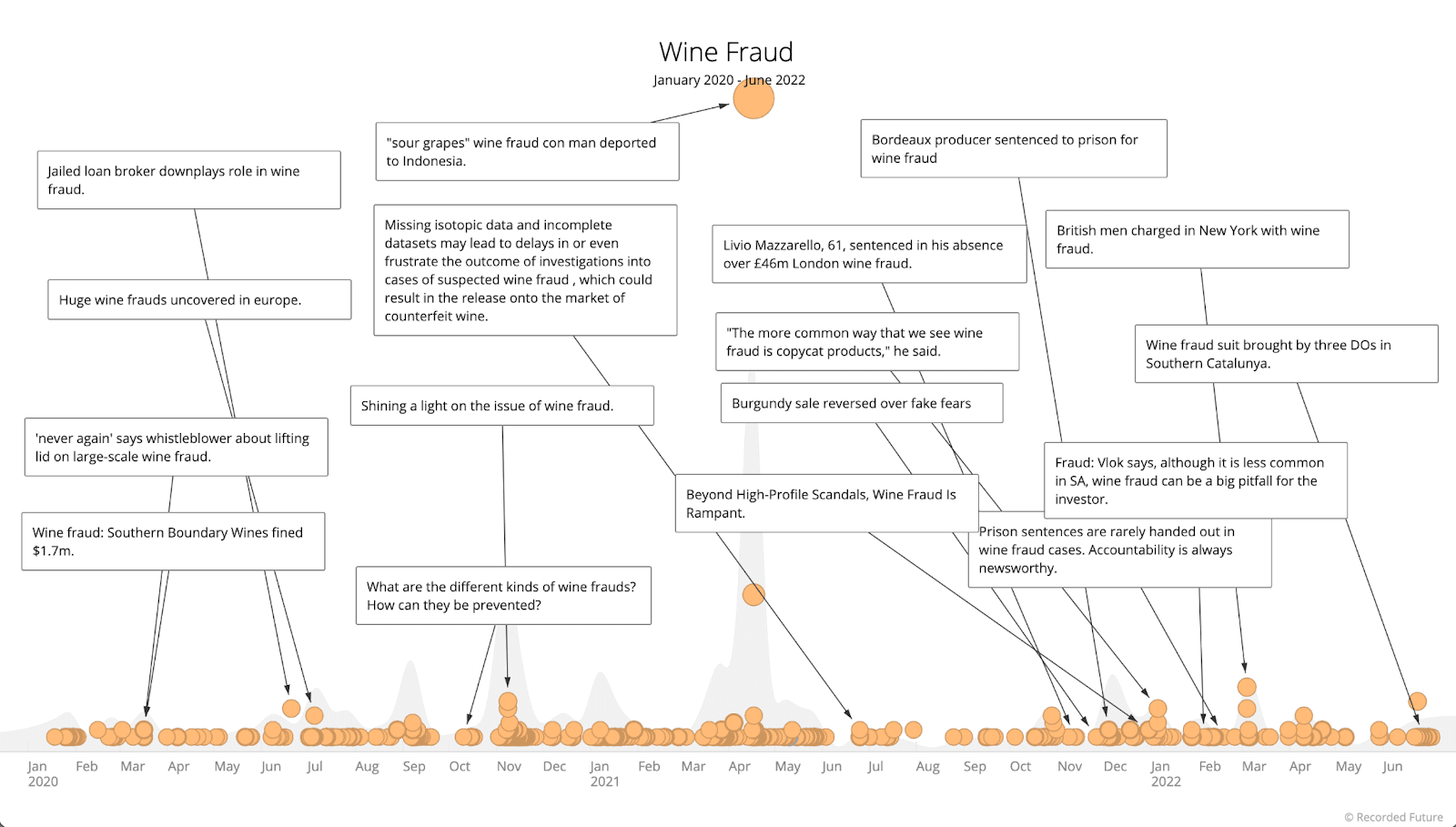

Figure 2: Reported cases of wine fraud between January 2020 and June 2022 (Source: Recorded Future)

Figure 2: Reported cases of wine fraud between January 2020 and June 2022 (Source: Recorded Future)

The last several years have seen an uptick in wine fraud, likely as a result of two different trends. In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, between March and June of 2020, wine and spirit sales, including online orders, increased between 20% and 40% across the United States. In Italy, the growth was even more pronounced, with online wine sales increasing by 149% in the first 10 months of 2020. This growth in online wine sales created more opportunity for wine fraud as many of the traditional means of vetting wine were limited or shut down at the start of the pandemic. According to the Journal of Financial Crime incidents of counterfeit wine and other goods purchased through online vendors increased significantly during the first 10 months of the pandemic, with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in the United States logging more than 223,000 complaints.

The increase in demand for wine also meant that more wine was being purchased through gray market channels (the gray/grey market refers to wine purchased outside of normal distribution channels). While wine purchased on the gray market is not necessarily counterfeit, experts warn that there is more opportunity for fraudulent wine to make its way into these markets.

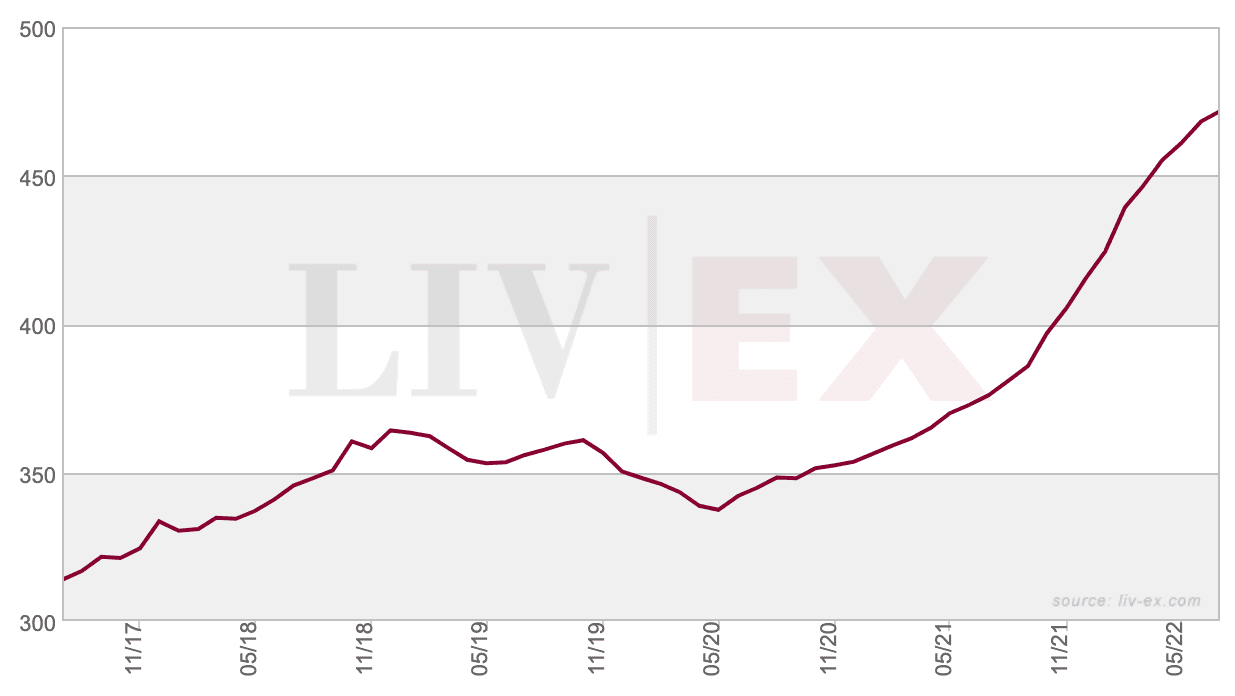

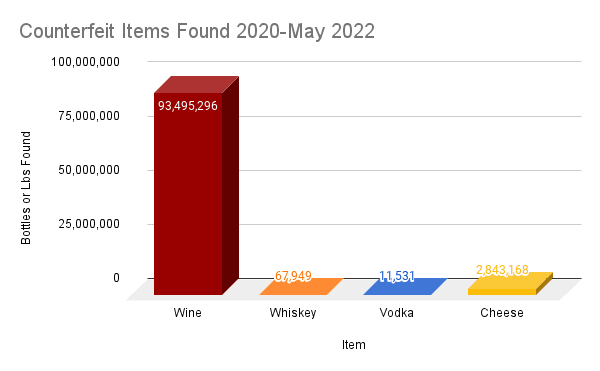

The second reason for the increase in wine fraud is that wine is increasingly seen as an investment. Bottles of Petrus regularly sell for $4,000, Screaming Eagle Sauvignon Blanc for $5,800, and Domaine de la Romanee-Conti for $25,000 at release, with prices almost always increasing on the secondary market. That means wine can be incredibly valuable to investors. According to Liv-ex, the Fine Wine 1000 Index has seen an increase in value of 49.1% over the past 5 years, while the Burgundy 150 has seen an increase in value of 118.3% during the same period.

Figure 3: Liv-ex Fine Wine 1000 Growth Chart along with the indices that make up the Fine Wine 1000, reprinted with permission from the Liv-ex website

Figure 3: Liv-ex Fine Wine 1000 Growth Chart along with the indices that make up the Fine Wine 1000, reprinted with permission from the Liv-ex website

As wine has gotten increased attention as an investment opportunity it has attracted more fraud, especially as new investors enter the market. This type of counterfeit wine often gets the most attention, with the examples of Rudy Kurniawan and the “Thomas Jefferson” wines usually being cited.

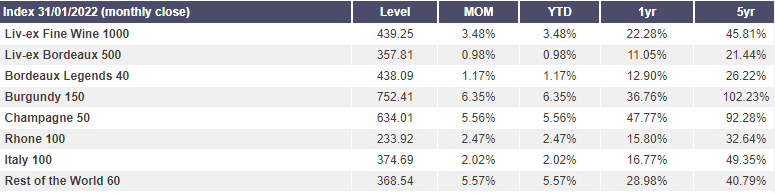

But high-end wine fraud actually makes up a very small percentage of counterfeit wine. Most of the wine that gets counterfeited is everyday drinking wine. In fact, of the more than 93 million bottles of counterfeit wine Recorded Future was able to track between January of 2020 and June of 2022, fewer than 5,000 were confirmed to be wines that would qualify as luxury wines.

Figure 4: Bottles or pounds of select counterfeit items publicly reported between January 2020 and June 2022 (Source: Recorded Future)

Figure 4: Bottles or pounds of select counterfeit items publicly reported between January 2020 and June 2022 (Source: Recorded Future)

Again, there is likely a reporting bias here. Many of the reports of wine fraud are made by law enforcement after tracking down the counterfeiters. So, when Italian authorities seize 35 million bottles of counterfeit Prosecco they will issue a report. But when a collector, especially a new collector, experiences wine fraud they may not be aware of it or, if they are, they may be too embarrassed to report it publicly; in fact, counterfeit bottles often get recycled into the market as they are resold.

Types of Wine Fraud

As was already hinted at, there are several types of wine fraud and different ways that wine fraud can be committed.

The most common type of wine fraud observed in our analysis is the attempt to pass off cheaper wine as more expensive wine at scale. For example, in one case a winemaker from the Médoc region of southwest France imported cheap wine from Spain and other areas and passed it off as more expensive Bordeaux wine. The counterfeiters had their own bottling facility and the ability to print their own labels. They produced and shipped hundreds of thousands of counterfeit bottles of wine before being caught by French police.

In another example, police in Italy arrested a group of counterfeiters who produced 35 million bottles of fraudulent wine, including Prosecco and Pinot Gris. The wines were falsely labeled as Denominazione di Origine Controllata (DOC), despite the wine not meeting the requirements for those labels. The wines were distributed to grocery stores and wine shops throughout Europe with the misleading labels.

In another example, a group of criminals in Italy passed off 80,000 bottles of Sicilian table wine as wine from Tuscany, specifically the Bolgheri Sassicaia DOC. This was truly an international operation with the bottles being produced in Turkey and the labels printed in Bulgaria, including security tags.

These operations tend to be large and, based on available information, almost always involve a winery or employees of a winery who can easily bottle hundreds of thousands or even millions of bottles of counterfeit wine and have access to the necessary equipment to produce the necessary labels. These almost always go unnoticed by consumers and are uncovered and stopped by law enforcement.

The second largest type of wine fraud, based on Recorded Future’s research, involves winemakers adding disallowed ingredients to their wine. Depending on the region, and local alcohol laws, these ingredients can include sugar, juice, wines from other regions, or even banned chemicals.

An example of this type of fraud is the winemaker in Italy who produced “more than 130,000 cases” of counterfeit wine. The winemaker used cheaper wine, sugar, and water to produce the wine and then labeled the wine Oltrepò Pavese, a protected DOC wine region. The difference between this type of fraud and the first type of wine fraud is that this winery was part of the Oltrepò Pavese DOC and produced legitimate Oltrepò Pavese wine, but it also produced and exported the fraudulent Oltrepò Pavese wine as well.

In another example several winery employees and a winemaker in New Zealand pleaded guilty to charges of mixing vintages, blending grapes from different regions (while labeling the wine with the more prestigious region), and selling “non-compliant” Sauvignon Blanc. In total more than 174,000 bottles of fraudulent New Zealand wine may have been exported by these counterfeiters before they were caught.

The final type of wine fraud, and the one that tends to draw the most attention despite being more rare, is counterfeit wine designed to dupe collectors and investors. These cases involve small batches of counterfeit expensive wine and are aimed at wealthier collectors.

Some counterfeit wines are relatively easy to spot, such as a livestream offering a knock-off 2014 Les Fortes de Latour for a fraction of the cost; others can be harder to spot. But as counterfeiters have improved their methods it is often hard to tell that the wine is fake, as in the case of 8,000 bottles of counterfeit Penfolds that were unearthed in China, until you open and taste it (and sometimes not even then).

Counterfeiting Wine

There are generally two ways counterfeiters create fake wine:

- Bottle refill

- Bottle recreation

There is a third type of fraud that is not necessarily counterfeit, but should be noted: selling bottles of wine that have been exposed to heat or other extreme temperatures primarily due to natural disasters as pristine (pristine meaning the wine has been stored at the proper temperature and humidity). This is a different type of fraud that is outside the scope of this report, and largely handled by insurance companies.

Bottle refill is an easy way to create fake wine. Old wine bottles are readily available on sites like eBay, often with a cork; people also regularly dumpster-dive at nicer restaurants looking for wine bottles, and staff from those same high end restaurants have even been known to save and sell expensive bottles. These same bottle refill techniques are also used to produce counterfeit whiskey and spirits.

Another technique wine thieves use to create counterfeit wine is to use a Coravin or similar tool to siphon wine and replace it with cheaper wine. Coravin is a tool used by wine professionals to sample wine without having to open the bottle. It has a very thin needle that can pass through the capsule (the foil that is often wrapped around the lid of the wine bottle) and the cork, take a sample of wine, and replace the sample with an inert gas. This allows a wine professional to ensure that a bottle of wine is still good without having to open it; you can also use this method to drink a glass of wine from a nice bottle without having to uncork it.

Similar to the way threat actors have co-opted tools designed for red teams to launch attacks, wine counterfeiters have figured out that they can use the Coravin to siphon off the wine, enjoy it, then fill the bottle with cheaper wine and sell it on the gray market. Of course, this process won’t make a counterfeiter a lot of money — buying an expensive bottle of wine, drinking it, and reselling the bottle with fake wine in it is, at best, a break-even activity.

Unless you steal the wine.

Wine thieves often find it surprisingly easy to steal from high-end restaurants, hotels, personal wine cellars, and even directly from wineries. Of course, thieves can sell the wine directly on the gray market or to unsuspecting wine collectors, but many want to enjoy the wine, replace it with a lesser wine, and then sell the bottle to unsuspecting collectors.

The second type of counterfeit wine involves recreating bottles of rare or highly sought-after wine and passing those recreations off as legitimate. Counterfeiters use modern technology to copy or recreate as much of the bottle as possible, from copying labels to bottle designs, corks, and capsules. They will then take steps to “age” the bottles. Of course, many counterfeiters will also go old school and steal labels and corks directly from the winery or from the printers used by the winery, in effect conducting a supply chain attack.

There are a number of techniques that counterfeiters use to artificially age wine bottles. One technique involves using coffee grounds or tea leaves to artificially age the labels (this is why wine fraud investigators will often tell people to smell the label — real wine labels should not smell like tea or coffee). Fraudsters also use various techniques to make their wine bottles appear old. A combination of tobacco, sanding, and dirt are often used to make a bottle appear older than it is. To make things simpler, some counterfeiters will use bottles from the same vineyard, but of a different vintage. A bottle of 1982 Cheval Blanc from Bordeaux goes for around $1,400 on the secondary market, but a bottle of 1985 Cheval Blanc sells for less than half of that. A counterfeiter could buy a case of the cheaper wine, change the label, and sell it as the 1982 vintage. The counterfeit wine will have the correct bottle and close to the correct label, and it would have all the characteristics of a Cheval Blanc (because it is), though it won’t taste anywhere near as good as a true 1982; in other words, a very hard-to-spot fraud. In the meantime the counterfeiter will likely clear more than $8,000 per case and will repeat this process dozens or hundreds of times a year.

Countering Fake Wine

In the same way that many organizations don’t think they are being targeted by cyber criminals, a lot of wineries assume that they are not being targeted by counterfeiters. As shown throughout this report, wines of all price ranges and geographic location can be targeted by counterfeiters. Those wineries who are concerned about counterfeit wine have generally adopted a “defense in depth” style approach, one that involves physical and technical challenges to counterfeiters.

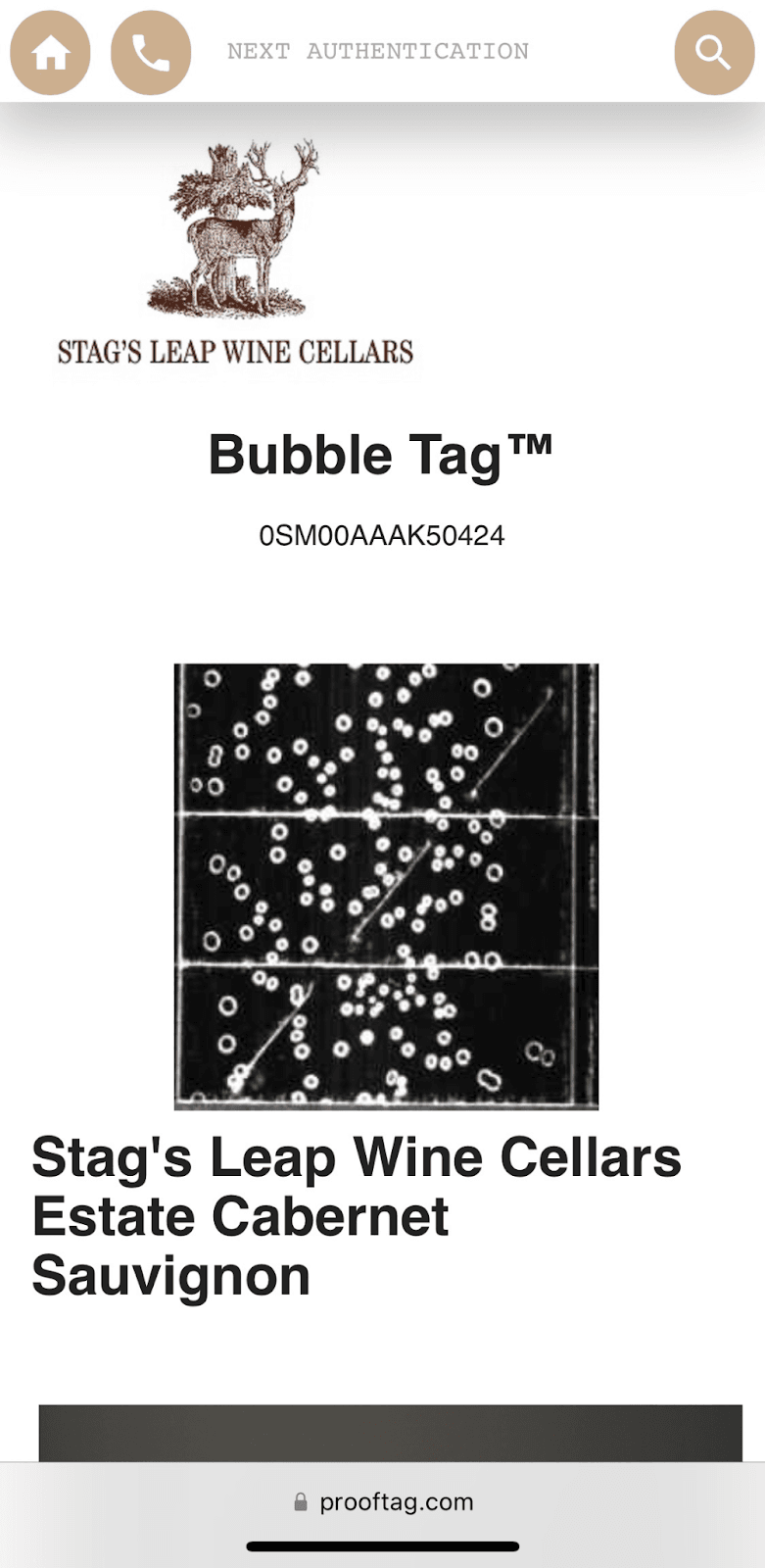

The security tag is a countermeasure often taken by high wineries that are willing to pay the additional cost to protect themselves. Prooftag is one company that provides this service, which they call Bubble Tag®. Bubble Tag® is a two-step authentication process.

Figure 5: Prooftag Bubble Tag® on a bottle of 2018 Stag Leap Wine Cellars Fay Cabernet Sauvignon (photo by author)

Figure 5: Prooftag Bubble Tag® on a bottle of 2018 Stag Leap Wine Cellars Fay Cabernet Sauvignon (photo by author)

As shown in Figure 5, the Bubble Tag® is attached to both the capsule and the wine bottle itself to prevent tampering. If a counterfeiter removes the capsule, the Bubble Tag® is destroyed and the wine can immediately be considered suspect. The example in Figure 5 is from a bottle of 2018 Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars Fay. A consumer in a wine shop or someone who just received a bottle of this wine from an online store can scan the QR code, which will take them to the Prooftag website as shown in the first part of Figure 6.

One big challenge with security tags is that counterfeiters have figured out how to safely remove them and place them on counterfeit bottles without breaking them. Counterfeiters have also been known to target the print shops where these are printed.

Figure 6: Authenticating wine on the Prooftag website (Source: Prooftag)

Figure 6: Authenticating wine on the Prooftag website (Source: Prooftag)

On the Prooftag website, the buyer can enter the 14-digit number located on the Bubble Tag® and they will be presented with an image, shown on the right side of Figure 6. This image should match the “bubbles” in the foil on the Bubble Tag® of that wine. Each bottle of wine has a unique pattern of bubbles on the foil. If the patterns match, then the wine is authentic. In effect, this serves as a form of multi-factor authentication for the wine.

But that is not the only form of anti-counterfeiting measure on this particular bottle of wine. In addition to the Bubble Tag®, the winery has had custom bottles, also known as proprietary glass, made with the word Fay in a circle embossed on them (see Figure 7). This antifraud measure is similar to being the only person who locks their car doors on the street — it will not deter someone who is determined to break into the car, but it will likely make a casual car thief look elsewhere. At the very least it helps quickly prove a bottle is counterfeit after the fact, when it doesn’t have the correct markings.

Figure 7: The word FAY embossed on a bottle of 2018 Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars Fay Cabernet Sauvignon (photo by author)

Figure 7: The word FAY embossed on a bottle of 2018 Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars Fay Cabernet Sauvignon (photo by author)

This adds another layer of complexity to counterfeiting attempts. A counterfeiter cannot use just any wine bottle — they have to either custom-make one, which is prohibitively expensive, or obtain a number of these bottles from restaurants, hotels, or other locations.

By taking a “defense in depth” approach to securing their wines, like this one, winemakers hope to foil counterfeiting attempts.

Another excellent example is Château Smith Haut Lafitte, which has several layers of security on their bottles designed to make it harder to counterfeit. The bottles also use the Prooftag Bubble Tag®, as shown in Figure 8, each bottle has 3 Fleur de Lis engraved on the shoulder (Figure 9), and “SHL” has been engraved on the bottom of the bottles (Figure 10).

Figure 8: The Bubble Tag® on a bottle of 2012 Château Smith Haut Lafitte (photo by author)

Figure 8: The Bubble Tag® on a bottle of 2012 Château Smith Haut Lafitte (photo by author)

The images used in this section describing the anti-fraud measures that Château Smith Haut Lafitte has taken are from a bottle of the 2012 vintage. In other words, a lot of wineries have been thinking about and fighting wine fraud for a while. For example, Château Margaux has been laser etching their wine bottles since 1989, starting in 1995 each individual bottle received a unique etching, and starting with the 2011 vintage Château Margaux also adopted a bubble code security tag.

These aren’t the only anti-fraud measures that wineries are taking to secure their bottles. Some wineries, like Château Mouton Rothschild change their labels every vintage (though this is not always purely an anti-fraud measure), in theory making them harder to forge. Other wineries use custom ink and specialty paper for their labels and others, like Château Troplong Mondot, embed hidden images or text on their labels.

Figure 9: Fleur de Lis on a bottle of 2012 Château Smith Haut Lafitte (photo by author)

Figure 9: Fleur de Lis on a bottle of 2012 Château Smith Haut Lafitte (photo by author)

Figure 10: “SHL” engraved on the bottom of a bottle of 2012 Château Smith Haut Lafitte (photo by author)

Figure 10: “SHL” engraved on the bottom of a bottle of 2012 Château Smith Haut Lafitte (photo by author)

The hidden images or text used by wineries on labels to counteract fraud can only be seen by using an ultraviolet light. For example, Figures 11 and 12 show the label of a 2017 Château Troplong Mondot in regular light and with an ultraviolet light shone on it.

Figure 11: 2017 Château Troplong Mondot photographed in regular light (photo by author)

Figure 11: 2017 Château Troplong Mondot photographed in regular light (photo by author)

As you can see in Figure 12, when you shine an ultraviolet light on the wine bottle a cursive “TM” is visible in the bottom-left corner of the label. Again, this should make it more difficult to counterfeit the label and the symbol or text (as well as its location on the label) can change from vintage to vintage without disturbing the label itself.

The Bordeaux region as a whole has been at the forefront of implementing anti-fraud measures for their wine, which is a remarkable contrast to 2007 when many of the top Châteaux in Bordeaux did not consider counterfeit wine a problem. Or, if they did, to quote the owner of the famed Château Le Pin, Jacques Thienpont, “I have no idea about the size of the problem; I prefer not to know”. Again, this parallels the attitude that many had toward cybersecurity, which is that it is better to not know about the problem because then you don’t have to address it.

Fortunately, wine regions all over the world are taking counterfeit wine seriously and are taking steps to prevent it. Research against wine fraud is ever-evolving, with wineries exploring technologies like Blockchain as a means to defeat wine fraud.

Figure 12: 2017 Château Troplong Mondot photographed in ultraviolet light (photo by author)

Figure 12: 2017 Château Troplong Mondot photographed in ultraviolet light (photo by author)

Are Anti-Fraud Solutions Working?

Despite investment from the wine industry and the continued countermeasures taken by individual wineries, the consensus is that wine fraud continues to grow. But because most wine fraud goes undetected or unreported no one knows for sure how big the counterfeit wine market is; the number most often mentioned is that 20% of all wine on the market is counterfeit. That number has been relatively consistent since 2013, but it is also possible that reports are recycling the same number given that there are no official numbers to report.

So, if there is increased awareness of the problem by wineries and increased scrutiny on wine counterfeiting, why is it that wine fraud still appears to be a rampant problem? There seem to be a number of reasons for that.

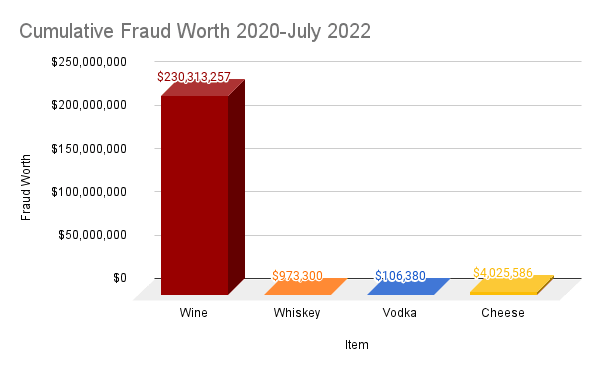

For one thing, wine fraud is very profitable. As Figure 13 shows, wine fraud was incredibly profitable compared to the other types of fraud we tracked for this report. Recorded Future was able to track $230 million of publicly reported wine fraud between January of 2020 and June of 2022. Once again, that was just the fraud publicly reported; the real number is likely significantly higher.

Any type of criminal activity that attracts this type of profit is going to attract more criminals, and those criminals will invest money to improve their chances of continued success.

Figure 13: Wine fraud compared to other types of tracked fraud (Source: Recorded Future)

Figure 13: Wine fraud compared to other types of tracked fraud (Source: Recorded Future)

This means that wine counterfeiters will invest in tools and technology that will allow them to make better and harder-to-detect counterfeit wine. As with other types of criminals, wine counterfeiters will often reinvest money earned to make even more effective forgeries. Thus it becomes a cat-and-mouse game between wineries and wine fraudsters — as wineries improve the security of their wine bottles, the counterfeiters figure out ways around that security.

It also doesn’t help that a lot of anti-fraud techniques wind up being “security theater”. Many of the measures designed to stop counterfeiters do not effectively address the way that wine counterfeiters work. They provide more of an illusion of security than actual security.

Take the bubble codes in Figures 5 and 8: they do provide a way for tracking a wine and ensuring that the bottle is authentic, but they don’t actually tell the purchaser whether or not the wine inside the bottle is authentic. Bubble codes are most often little stickers attached to the bottom of the capsule and the top of the neck of the bottle (as shown in those two figures). But one of the ways that we know wine counterfeiters like to replace wine is by using a needle of some type to extract and replace the wine without disturbing the capsule or the cork. If these bubble tags were attached to the top of the neck and ran across the top of the capsule to reattach on the other side of the neck, they could add another layer of protection, especially if the tag was designed to break if punctured.

Another problem with the bubble tags is the longevity of these businesses. Winemakers in Bordeaux, Burgundy, Barolo, Barossa, and Napa all think in terms of decades, as do the people who drink these wines. Will the companies behind bubble codes still be around in 30 years to authenticate a great 2010 vintage from Bordeaux?

Even now, there can be problems with these tags. Every wine in Italy that receives a DOCG certification is assigned a unique serial number that is placed on a tag attached to the bottle, similar to the bubble codes (without the bubble) as shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14: Security tag with unique serial number on a bottle of 2012 Michele Chiarlo Tortoniano Barolo (photo by author)

Figure 14: Security tag with unique serial number on a bottle of 2012 Michele Chiarlo Tortoniano Barolo (photo by author)

The problem is that there does not seem to be a place on the Barolo Consortium’s website (or anywhere else) to verify that number. Other consortiums, such as the Brunello Consortium, do have forms for consumers to enter codes and verify their wine, but Barolo does not. It is likely that there are ways for distributors and importers to verify these wines, but with the rapid increase of online wine sales and the awareness of wine fraud, more and more consumers will likely want to be able to verify these codes directly.

Another problem is that these tags are often so poorly applied that they fall off and, if consumers don’t know to look for them, they won’t question the lack of tags.

Consumer education is another problem with many of these anti-fraud solutions. This education problem is partially explained by the fact that many of these solutions were not originally developed for the wine drinker. They were developed for wine buyers, distributors, and importers to verify the authenticity of the wine they were buying for distribution or for their restaurant, hotel, or wine shop. But with the growth of online sales and online wine auctions more consumers are looking to understand how to verify their wine, and there is very little instruction available to them as to how to do that.

That lack of knowledge doesn’t just apply to consumers. As research for this report I visited wine and whisky shops around the United States looking for security tags, hidden text on labels, and other security mechanisms I had researched. Very few of the wine shop employees I talked to had any idea what the QR codes on them were for or what the bubble codes meant. In fact, one employee politely but firmly asked me to leave the store as soon as I started talking about counterfeit wine (after that, I also decided to stop scanning wine bottles at the shops with my ultraviolet light).

It is understandable that wineries may not want to make all of their anti-fraud techniques readily available to everyone. After all, publishing all the protections in place may make the job of counterfeiters easier. But what good are the protections if consumers don’t know about them? There needs to be a balance between wineries keeping their security measures proprietary and consumers being able to quickly conduct a check of their bottles to ensure they are legitimate (without necessarily having to involve an intermediary).

One way to do that could be to provide more public education at the point of sale. Signs or placards in wine shops letting consumers know how to verify their wine is authentic might entice consumers to be better informed about what to look for when it comes to fraudulent wine. Websites that sell or auction wine should have an education section on how consumers can verify their wine as well. Merchants may not want to advertise the fact that counterfeit wine exists, but they should consider it an additional defense in depth step. Merchants can outline the steps they take to verify wine before they sell it, but also let consumers know they can follow similar steps.

As long as wine fraud is still a big problem — and considering it has been around for at least 2,000 years, it is likely not going away — everyone is going to have to be involved to ensure that counterfeit wines are discovered and reported and that action can be taken against the counterfeiters.

Spirits

Counterfeit spirits are a bit more challenging to track. Most of the counterfeit spirit operations that were publicly reported between January of 2020 and June of 2022 involved fewer than 4,000 bottles. One exception was a counterfeit whisky group out of Spain that could have resulted in up to 300,000 bottles of counterfeit whiskey being distributed throughout Spain. The equipment and filled bottles that were seized were worth about $970,000.

Scope of Spirit Fraud

According to our research, the two most commonly found counterfeit spirits are whisky and vodka. Between January of 2020 and June of 2022 Recorded Future was able to identify dozens of reports of fraudulent whisky and vodka being sold. Some of these were very localized, such as pub owners caught selling watered-down vodka. Leaving out the one large counterfeit ring mentioned above, the average number of counterfeit whisky and vodka bottles involved in each publicly reported case between January of 2020 and June of 2022 was 590, significantly smaller than the number involved in counterfeit wine cases. This despite general industry consensus that vodka is the most counterfeited spirit, largely because vodka is clear and has almost no taste so it is easy to counterfeit.

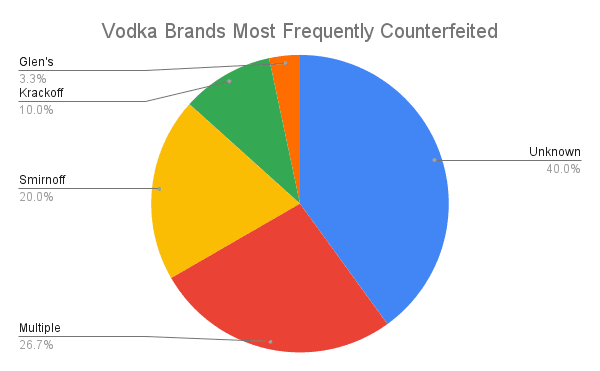

There is also a difference between which brands are counterfeited. Of the publicly reported vodka fraud cases, most of the time the brand was unknown or the counterfeiters were reproducing multiple brands; but as Figure 15 shows, when a specific brand was mentioned Smirnoff was the most popular.

Figure 15: Vodka brands most frequently counterfeited based on public reporting (Source: Recorded Future)

Figure 15: Vodka brands most frequently counterfeited based on public reporting (Source: Recorded Future)

Smirnoff accounted for at least 20% of all publicly reported counterfeit vodka cases, and the real number is likely higher.

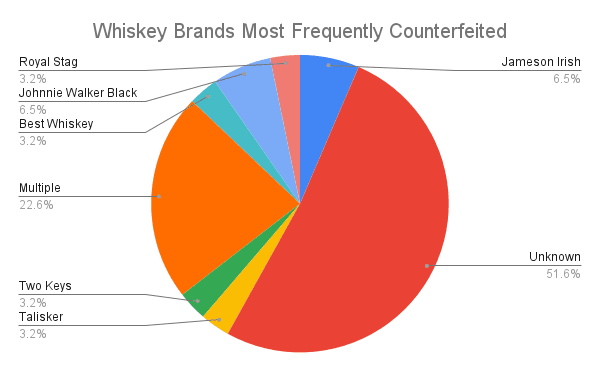

Whisky brands, on the other hand, were more evenly distributed. As Figure 16 shows, again “Unknown” and “Multiple” brands account for most publicly reported incidents of fraud — though accounting for 74.2% of incidents versus 66.7% for vodka — but the most popular named counterfeit brands, Johnnie Walker and Jameson, only account for 6.5% of incidents each, as shown in Figure 16.

As with wine, the market for counterfeit whiskey seems to have expanded with the growth of online marketplaces and auction sites. As new collectors have garnered interest in whisky, especially in rare or hard-to-find brands, the counterfeiters have stepped up to fill the gap left by a lack of supply. Even reputable auction houses have been fooled by some of the counterfeit whisky.

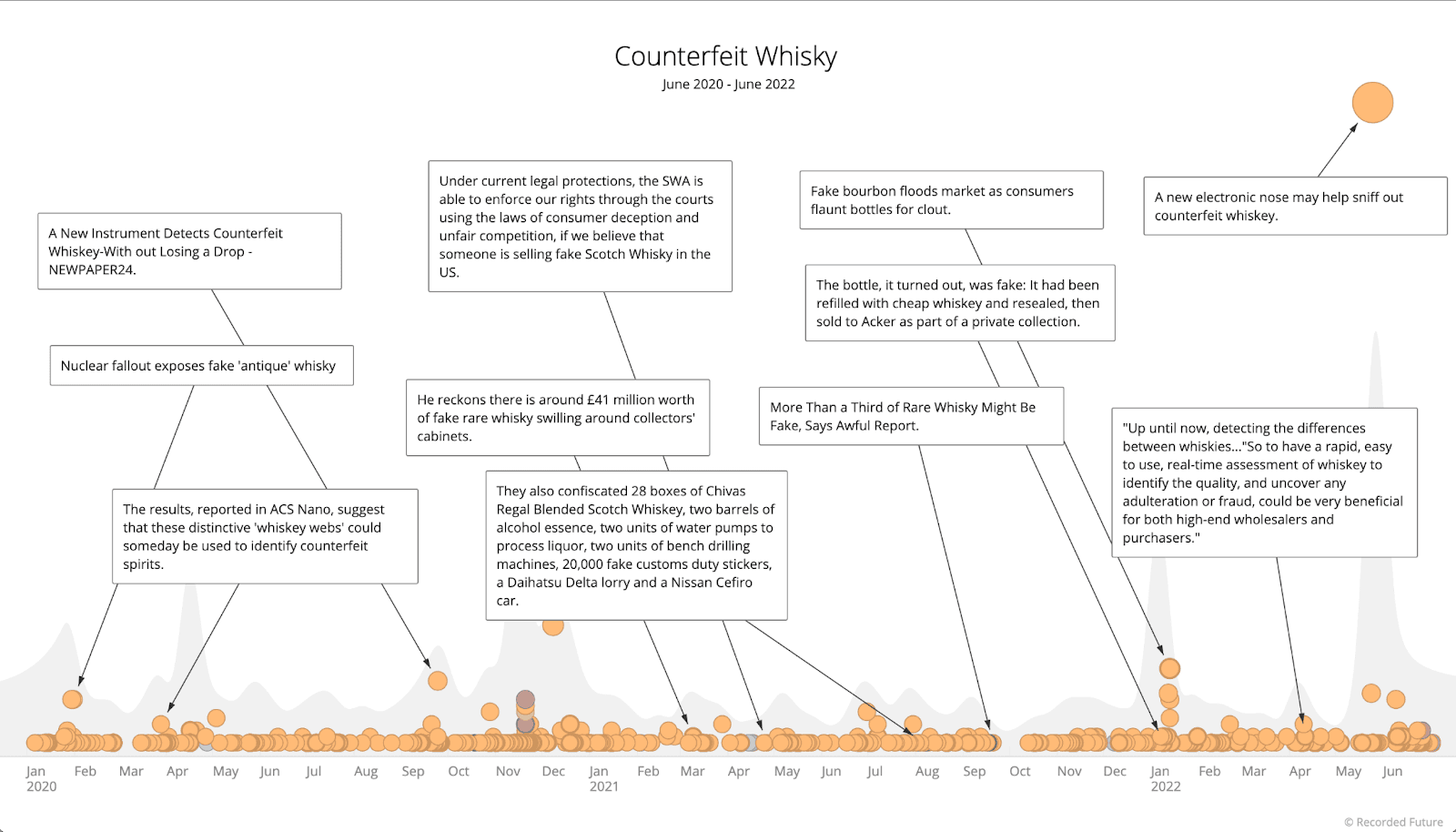

Reported cases of whisky fraud have popped up fairly regularly and consistently over the past 2.5 years, as shown in Figure 17. But, as with wine fraud cases, the fear is that most cases of fraud are never uncovered or, if they are, never publicly reported. This means we likely don’t have an accurate picture of the total scope of whisky fraud.

Figure 16: Whisky brands most frequently counterfeited based on public reporting (Source: Recorded Future)

Figure 16: Whisky brands most frequently counterfeited based on public reporting (Source: Recorded Future)

Figure 17: Reported cases of whisky fraud between January 2020 and June 2022 (Source: Recorded Future)

Figure 17: Reported cases of whisky fraud between January 2020 and June 2022 (Source: Recorded Future)

Unlike whisky fraud, most cases of counterfeit vodka involve sales to pubs, restaurants, distributors, and other institutions rather than directly to the consumer. Interestingly, online sales of vodka have increased during the pandemic just like wine and whisky sales, but because there isn’t a perceived scarcity of certain vodka brands it doesn’t appear to have spurred on a corresponding increase in counterfeit vodka being sold online. Alternatively, there may have been an increase, but it hasn’t been noticed.

The regional distribution of whiskey (Figure 18) and vodka (Figure 19) are also different.

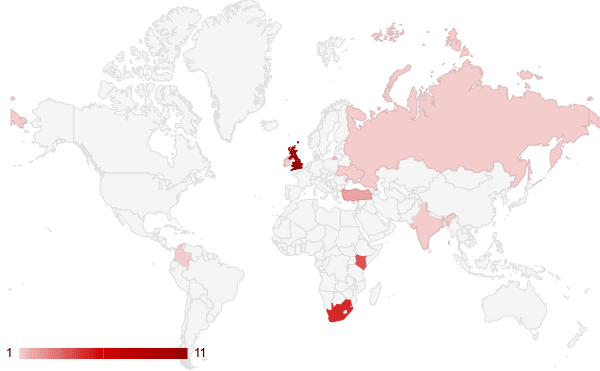

Figure 18: Scope of reported whisky fraud around the world January 2020 to June 2022 (Source: Recorded Future)

Figure 18: Scope of reported whisky fraud around the world January 2020 to June 2022 (Source: Recorded Future)

Figure 19: Scope of reported vodka fraud around the world January 2020 to June 2022 (Source: Recorded Future)

Figure 19: Scope of reported vodka fraud around the world January 2020 to June 2022 (Source: Recorded Future)

Whisky fraud appears to be more widespread and distributed, with publicly reported cases of whisky fraud in 15 countries versus 10 countries for counterfeit vodka. Unlike with cases of wine fraud, India appears on maps showing cases of both whisky and vodka fraud.

Types of Spirit Fraud

Unsurprisingly, spirit fraud tends to mimic wine fraud, but there are some differences. Most of the whisky fraud reported involved bottle refill or small-scale fake bottle fraud. Unlike most cases of wine fraud, even these small-scale cases can result in victims dying. This is a recurring theme with spirit fraud, where the chemicals used to make fraudulent spirits can result in serious injury or death to the victims.

Most cases of publicly reported spirit fraud involved selling spirits locally. Counterfeiters would produce fake whisky or vodka and then ship the fraudulent spirits to shops in the country. The focus on the local market is likely to avoid detection by customs authorities who would likely easily spot some of the more amateur fake spirits.

Countering Fake Spirits

On the surface, vodka distillers appear to be leaving the process of stopping counterfeit vodka to law enforcement. There is no mention of counterfeit or fraud on the Smirnoff website, for example; Diageo, Smirnoff’s parent company, only mentioned counterfeit once on their site. There are reports from 2014 that Smirnoff, among other brands, added a special dye to its vodkas that would allow inspectors to quickly test the authenticity of their spirits. But there does not seem to be any information about this program on the Smirnoff or Diageo sites, so it is unclear whether this is still in operation.

Whisky producers, on the other hand, possibly spurred by the alarming increase in headlines about counterfeit products being sold, seem to be taking more proactive steps to prevent counterfeiting. Many of these anti-fraud steps mirror those of the wine industry. Whisky producers have adopted anti-fraud measures such as:

- Laser etching of individual serial numbers on bottles

- Adding design elements to bottles to make them harder to replicate

- Embedding images or text on labels that are only viewable under ultraviolet light

- Adding security tags to capsules

- Some producers have also explored blockchain-based solutions

One example is The Macallan, which has added security tags to all of their bottles. The tags, an example of which is shown in Figure 20, include a QR code and a holographic image of The Macallan Estate. The QR code takes anyone who scans it to the The Macallan website, where the QR code is verified and the visitor is redirected to the company’s home page.

Even though it appears that each security tag has a unique number on it, those numbers are not used for any verification purposes. Instead, the fact that the QR code is valid combined with the holographic image of The Macallan estate are considered enough to verify that the bottle of whisky is authentic.

Figure 20: Security tag on a bottle of 12-year-old The Macallan Scotch Whisky (photo by author)

Figure 20: Security tag on a bottle of 12-year-old The Macallan Scotch Whisky (photo by author)

While many of the anti-fraud measures used by whisky distilleries mirror those used by wineries, there are some interesting technical solutions being developed specifically for whisky that could help buyers and collectors better test the authenticity of their whisky in the future.

Researchers at the University of Glasgow and University of Strathclyde (both in Scotland) have developed an artificial tongue that can be used to “taste” whisky and compare the taste to a database of known whiskies to see if there is a match. Another example is that researchers at the Scotch Whisky Research Institute (SWRI) in Edinburgh have developed a laser light that can be focused into a bottle of whisky to determine its sugar levels, which is one way investigators use to verify the authenticity of whisky. Finally, researchers at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) have developed an “electronic nose” that distinguishes between different gases released by whiskies. The electronic nose, called NOS.E, can determine whether the contents of a bottle match the profile of different whisky distilleries on file.

None of these technologies are currently available to consumers, but this type of research could eventually find its way into the hands of consumers, making it easier to spot counterfeit whisky (at least until the counterfeiters determine how to make better fake whisky).

Protecting Against Spirit Fraud

What steps can consumers take to protect themselves from buying and drinking counterfeit spirits? A lot of it depends on the spirit in question. Whisky Advocate has a good run down of the steps consumers can take to protect themselves. In addition to their recommendations, some others to consider are:

- Always buy from a reputable source

- Confirm that any anti-fraud measures that are supposed to be in place actually are

- Don’t be afraid to contact the distillery if you have questions; as part of the research for this report, several distilleries were contacted via email and all were happy to answer questions

- Invest in a high-quality jeweler's loupe with an ultraviolet light in order to better examine labels and bottles

Some of the steps that apply to detecting fake whisky also apply to detecting fraudulent vodka. Much like early advice for detecting phishing or spam emails, determining if a bottle of vodka is counterfeit involves looking for spelling mistakes. It also can involve looking at the quality of the label and, in certain countries, looking for the tax or duty stamp. In addition, specifically for vodka, look for:

- The smell of fingernail polish (counterfeiters often use the chemical in nail polish to make vodka)

- Sediment in the bottle (vodka should have no sediment)

Though not exhaustive, these guidelines should help protect against many common types of spirit fraud.

Cheese

As with counterfeit wine and whisky, counterfeit cheese appears to be on the rise. Between January of 2020 and June of 2022 Recorded Future noted 2 dozen publicly reported cases of cheese fraud, costing organizations more than $4 million. As with the other counterfeit products in this report, those numbers are likely a gross underestimate of the total incidents and cost.

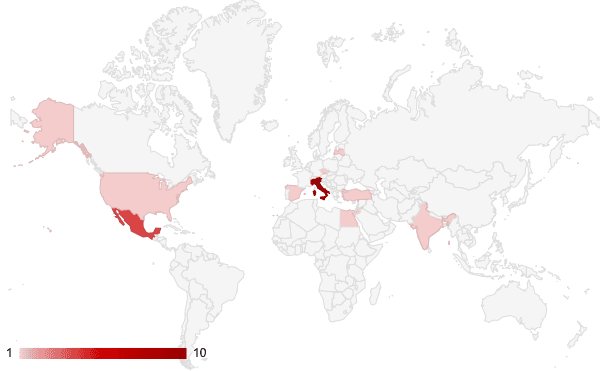

As shown in figure 21, Italy is really the center of cheese fraud, likely because Italy is one of the most aggressive countries when it comes to finding and prosecuting cheese counterfeiters. Cheese fraud is widespread and appears to be mostly centered around manufacturers using ingredients not allowed in certain cheeses, such as the dairy caught using cow’s milk in their Buffalo Mozzarella cheese; brands may also label their cheese improperly, such as cheese claiming to be Parmesan Reggiano, when it doesn’t meet the requirements to be labeled as such.

There are other — interesting — examples of cheese “fraud” as well. There was the dismissed class action lawsuit against the company that makes Bagel Bites™ for claiming the product contained Mozzarella cheese. There is also an ongoing lawsuit against Totino’s Pizza Rolls™ for, again, making false claims about the cheese used in their product.

Figure 21: Publicly reported cases of counterfeit cheese between January 2020 and June of 2021 (Source: Recorded Future)

Figure 21: Publicly reported cases of counterfeit cheese between January 2020 and June of 2021 (Source: Recorded Future)

Scope of Cheese Fraud

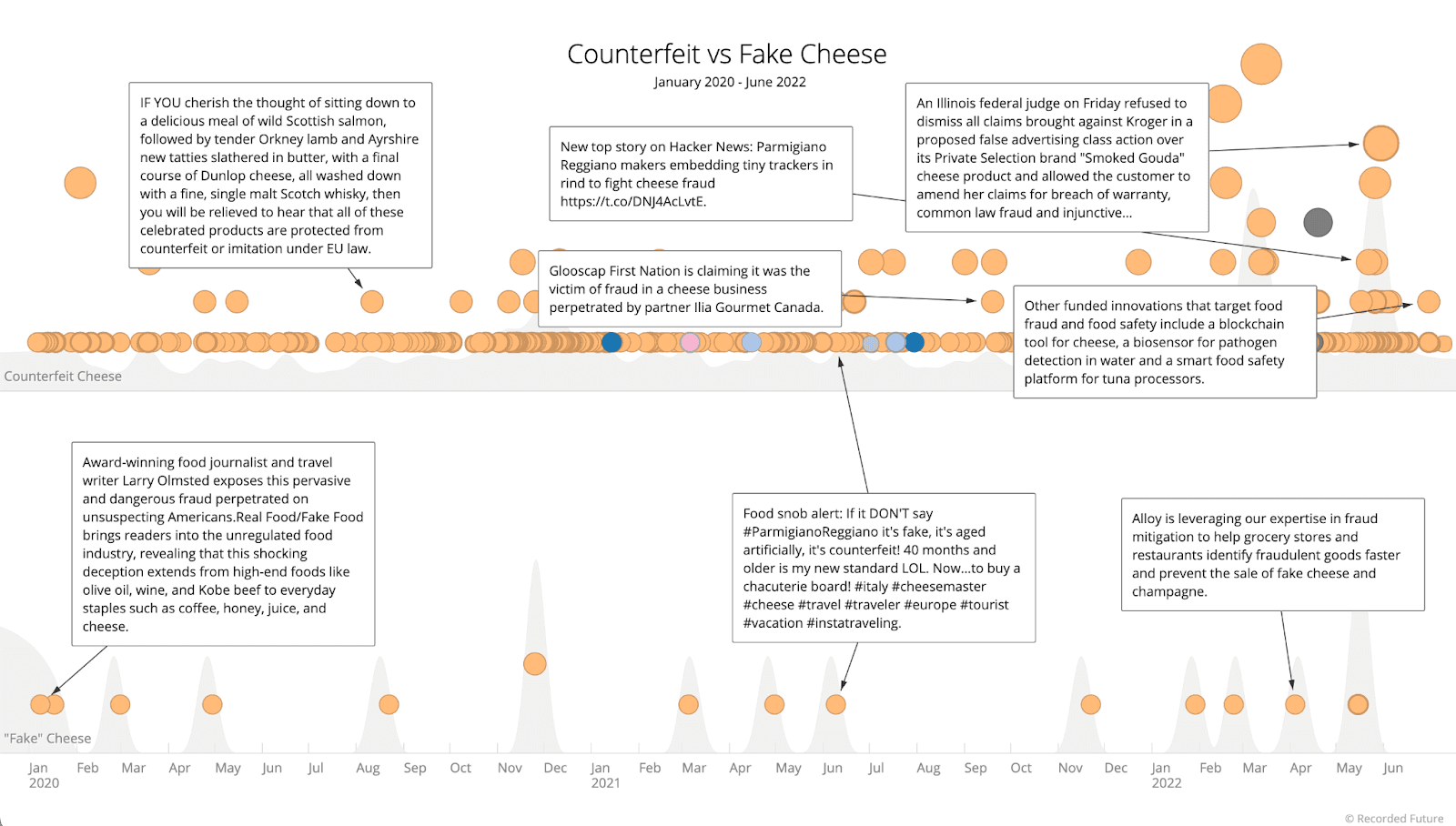

Figure 22: Reports of cheese fraud between January 2020 and June of 2021 (Source: Recorded Future)

Figure 22: Reports of cheese fraud between January 2020 and June of 2021 (Source: Recorded Future)

Charting the scope of cheese fraud is even more difficult than wine or spirit fraud because of the language challenges. Figure 22 shows how counterfeit cheese differs from wine and spirit fraud. Many headlines describing counterfeit products use the word “fake.” But, in the context of cheese, “fake” most often refers to imitation or vegan, which is not the same as counterfeit or fraudulent cheese. The widespread use of the word fake to interchangeably mean imitation and fraudulent cheese makes it difficult to track counterfeit cheese based on public reporting.

On the other hand, some “imitation” cheese is considered counterfeit. Parmigiano Reggiano is a great example of this — only cheese that is from the Parma or Reggio regions in Italy and produced a certain way can be called Parmigiano Reggiano, and in much of the world it is the only cheese that can be called Parmesan. The United States is an exception to that rule — Parmesan cheese in the US does not necessarily have to come from the Parma or Reggio regions, or even from Italy.

According to the Parmigiano Reggiano Consortium, while there were $2.63 billion in sales of Parmigiano Reggiano in 2019 worldwide, there were also $2.14 billion in counterfeit products sold using that name. That is just one example of a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) cheese; this type of counterfeit cheese is far more common than most people think.

Countering Fraudulent Cheese

Many cheese producers are turning to high-tech methods to counter counterfeit cheese. For example, Parmigiano Reggiano is using a specially designed chip that can be added to a Parmigiano Reggiano wheel to “track and trace” the cheese as well as allow customers to distinguish between real Parmigiano Reggiano and counterfeit versions. And it is not just the Italians — Swiss cheese makers are using DNA fingerprinting to counter counterfeit Swiss cheese.

While cheesemakers are taking proactive measures to make it harder to counterfeit their cheese, most of the work appears to be being carried out by law enforcement. The European Union recognizes 180 cheese PDOs and is very active in enforcing those PDOs. While there is a lot of focus on Parmigiano Reggiano because it is one of the most popular cheeses in the world, it is not the only cheese on the radar of law enforcement. In April, 400 tons of counterfeit Fioro Sardo cheese was seized from cheese makers in Italy; and in Turkey, the cheese makers behind Divle Tulumu have been fighting counterfeiters, with law enforcement assistance, as it tries to bring its cheese to the rest of the world.

Outlook/Conclusions

This report was designed to be an introduction to wine, spirit, and cheese fraud. It is hard to provide a thorough analysis of the problem in a report of this size, but it also provides additional resources for continued investigation.

Wine and whisky fraud is a growing problem that has been exacerbated by the growth of online sales along with the interest in rare wines and whiskies by collectors. On the other hand, cheese and vodka fraud is largely driven by the growth of large criminal counterfeiting rings that see an opportunity to sell fake products to unknowing buyers and store owners.

As with cybersecurity, the best way to fight the rampant counterfeiting occurring with these foods is the combination of proactive anti-fraud measures by manufacturers, stepped-up law enforcement action against counterfeiters, and increased consumer awareness of what to look for in legitimate products.

Recorded Future will continue to monitor for trends in counterfeiting of food products and update reporting as trends change.

Related