1 Key for 1 Lock: The Chinese Communist Party’s Strategy for Targeted Propaganda

Editor’s Note: The following post is an excerpt of a full report. To read the entire analysis, click here to download the report as a PDF.

This report assesses concepts related to the Chinese Communist Party’s international propaganda and information influence strategy. Topics covered include the party’s intent to segment audiences for targeted propaganda, theories about the selection of target countries, audience data collection, and the dissemination of tailored propaganda. Sources include authoritative Chinese materials, research by Chinese scholars, party-state media, procurement and corporate documents, among others. See Appendix B for more details on the methodology. The author, Devin Thorne, would like to thank Nathan Beauchamp-Mustafaga for his generous support. Additional information about the author can be found at the end of the report.

Executive Summary

To maximize its influence over international audiences, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is striving to tailor its propaganda to the specific interests of target populations. This approach, which is defined by the concept of “precise communication”, adapts the market segmentation tactics of advertisers to design content and dissemination methods that appeal to the preferences of a given group. China’s implementation of this strategy requires an in-depth understanding of target audiences, which is being attained — with the aid of international firms — through area studies research, in-country surveys, and online behavioral data. Precise communication has been heralded as a necessity and an era-defining shift by party-state media researchers; it is almost certainly driving an era of greater adaptability within the CCP’s propaganda apparatus, including party-state media’s deepening overseas localization, and very likely informing the CCP’s use of internet personalities for propaganda. Obstacles such as data privacy laws and international social media platform counter-measures are likely to inhibit the full realization of the CCP’s goal, but the party’s propaganda apparatus is actively seeking to find 1 “key” — a targeted message — for 1 “lock” — a specific audience that, from the party’s perspective, needs to be influenced.

Key Judgments

- The current era of the CCP’s external propaganda work is marked by the increasing granularity with which content can be tailored based on audience data and modern communication technologies.

- Chinese communication researchers propose segmenting audiences based on individual, community, or country-level characteristics such as culture, economic development, religious faith, customs, and personal interests.

- Achieving an in-depth understanding of target audiences is a prerequisite for success, and data from in-country surveys and online behavioral data collected with the assistance of domestic public opinion-monitoring companies and international research and social media firms is almost certainly being used to fulfill this demand.

- The CCP external propaganda apparatus is likely to continue expanding global data collection, seek to leverage advertising data, and evolve its tactics according to the latest advertising strategies that strive to circumvent hurdles such as those posed by data privacy laws — jurisdictions with lax regulations likely face greater risk.

- Party-state media are almost certainly among the leading implementers of precise communication, but a wide range of actors are also very likely to be directly or indirectly involved; some Chinese academics argue that precise communication should entail selecting the right communicator for maximum effect given the target and content.

- The precise communication concept is almost certainly intended to influence all of the CCP’s propaganda output, from news distribution through third parties, to TV show production, to the online and social media activities of party-state media and Chinese diplomats.

- The content disseminated by party-state media and other elements of the external propaganda apparatus is likely to become increasingly diverse, first according to country differences and then based on social strata and other community-level characteristics.

- New forms of media that adopt different approaches are likely to continue proliferating, with recent examples including online lifestyle influencers and newsletters.

20 Years of CCP External Propaganda Work

The Chinese Communist Party is striving to seize the “right to speak” (话语权) and to “set the agenda” (议题设置) internationally. Stated simply, this means creating an environment in which the party shapes what is talked about and how a given issue is perceived, with the goal of subsequently shaping the behavior of global audiences in ways that are beneficial to the CCP’s interests. Core efforts in the creation of such an environment are “news and public opinion work” (新闻舆论工作) and “public opinion guidance” (舆论引导). These concepts refer to long-term, continuous efforts to influence how people view social issues and government policies to “dispel misgivings and clear up confusion, [and] shape feelings” so that audiences have “correct” views as defined by the CCP.

To guide international public opinion on topics related to China and the party’s policies, the CCP’s strategic concepts for effectively conducting “external propaganda” (对外宣传) have steadily matured and its information dissemination architecture has expanded over the last 20 years. This movement began to surge in 2004. The party-state created new leading bodies for external propaganda work; resolved to craft a “great external propaganda pattern” (大外宣格局) that involved a variety of actors — central and local government entities, companies, academic institutions, and non-governmental organizations — “singing the same tune”; and expanded existing information dissemination channels such as the government and CCP spokesperson system.

A core part of the external propaganda upgrade that began in the early 2000s was the drive to expand party-state news media globally. By early 2009, China’s Ministry of Finance had reportedly budgeted 45 billion RMB (6.5 billion USD in January 2009) for the internationalization of China Central Television (CCTV; 中国中央电视台), Xinhua News Agency (新华新闻社), People’s Daily (人民日报), and other outlets. In June 2009, central authorities issued the “2009-2020 Overall Plan for Building My Country’s Key Media International Communication Capabilities” (2009—2020年我国重点媒体国际传播力建设总体规划), which outlined how central party-state outlets would build a modern system for international communication, use emerging media to create “breakthrough openings”, and improve editing, distribution, and product marketing to “form an international communication capability matching [China’s] level of economic development and international status”.

Chinese media’s internationalization, or “Going Out” (走出去), involves newspapers, TV stations, radio stations, and online media outlets establishing foreign offices, publishing and broadcasting in all major languages, paying for content inserts in foreign publications, distributing free news content, running ad campaigns online and offline, and establishing a social media presence on most foreign platforms. Since 2015, focus has increasingly been placed on “localization” (本土化), including by acquiring local media companies, hiring foreign staff, and partnering with local media for co-production.

2019 marked a turning point in China’s use of online disinformation, with foreign-facing computational propaganda increasing rapidly. The challenges posed to China’s international image by the party’s suppression of pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong (2019-2020) and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020-present) are almost certainly what drove greater numbers of Chinese diplomats onto global social media platforms. Further, under official instructions from the CCP’s leadership to “dare to flash the sword (敢于亮剑) . . . [and] counterattack all kinds of anti-China arguments”, the messaging from China’s propaganda apparatus has become more coercive in this period. However, observers noted an emerging “forceful” and “provocative” tenor in China’s diplomatic communications in earlier years and Taiwan has been the target of suspected Chinese online information influence operations since at least mid-2017.

In the post-2019 period, inauthentic campaigns and online personalities have become staples of CCP propaganda. YouTube, Facebook, and other global social media platforms have removed tens of thousands of accounts suspected of inauthentic manipulation attributed to China in the past 3 years. Such accounts amplify China’s diplomatic discourse and spread “political spam” related to CCP narratives. Chinese party-state media personnel, meanwhile, are becoming international influencers who use their “personal brands” to disseminate cultural, lifestyle, and political content. The voices of Chinese influencers are augmented by foreign personalities who collaborate with and are amplified by party-state media. The goal is to bring together multiple communicators “like voices in a choir” to reflect “a fuller . . . vision of China” in a tactic called “polyphonous communication” (复调传播).

Lastly, there has been a deepening government-directed focus in recent years on what new technologies, especially bulk data collection and artificial intelligence (AI), mean for propaganda work in China and abroad. Broadly, AI is seen as a tool for overcoming the challenges posed by the plurality of voices and speed of communication on the internet, which is considered the “most forward front of public opinion struggle”. Combined with the right data, Chinese communication researchers believe AI can assist the media and propaganda apparatus in achieving early warning of undesirable narratives before they go viral online, create content that more effectively resonates with audiences, and distribute content according to user interests.

Precise Communication as Propaganda Strategy

“Precise communication” or “precision communication” (精准传播) is the CCP’s strategic concept for maximizing the international influence of its news media and other propaganda work. The term is derived from advertising tactics that use consumer data to segment a target audience so that tailored marketing can successfully influence the behavior of a specific group. It is considered a “foundational principle” (基本原则) of external propaganda. A closely related concept is “One Country, One Policy” (一国一策), which emphasizes that there are differences between countries that should inform the design of China’s media content. Under precise communication and One Country, One Policy, the CCP’s propaganda apparatus is actively attempting to achieve a more in-depth understanding of target audiences and is striving to customize its output accordingly.

As part of this strategy, according to the CCP Central Propaganda Department (中共中央宣传部)-authored text Propaganda and Thought Work in the New Era, CCP cadres are instructed to

formulate country communication plans . . . persist in “content is king” . . . make news products more attractive . . . strengthen country communication research; go deep into the cultural context of foreign audiences; understand their value concepts, ways of thinking, and discourse style; [and] adopt targeted [针对性], differentiated [差异性], and individualized [个性化] communication tactics.

CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping (习近平) urged this approach at a mid-2021 Politburo study session:

use precise communication methods that stick closely to the audiences of different regions, different countries, [and] different groups, promote the globalized expression, regionalized expression, [and] audience differentiationalized expression of China’s story and . . . voice, [and] strengthen the effectiveness and affinity of [China’s] international communication.

Whereas the CCP’s propaganda apparatus was previously focused on solving “the issue of how China’s voice can ‘go out’”, the task now is to “solve how [China’s voice] can ‘go in’ [走进去]” to the minds and hearts of people overseas. Thus, the adoption of precise communication and One Country, One Policy mark an “era-defining leap” (划时代飞跃) away from the “standardized”, one-size-fits-all approach to communications of old, according to the director of the International Communication Research Office of __Xinhua__’s Journalism Research Institute (新华社新闻研究所国际传播研究室). As demonstrated in the “Theories of Target Selection” section of this report, precise communication entails targeting groups of people below the country-level. Scholars from Hunan University (湖南大学) asserted in a 2018 People’s Daily article that it is now necessary to “implement precise communication, [and] achieve [a situation in which] ‘1 key opens 1 lock’” — the locks being specific audiences and the keys being China’s tailored content.

2015: A New Era Begins

The precise communication-focused era of CCP external propaganda work very likely began in approximately 2015, based on trends in academic publishing and early examples of audience differentiation tactics. The strategy was almost certainly formally adopted — and broadly recognized as policy in China — by no later than 2017. It is almost certainly still influencing policies related to technology and media and “information content supply-side reform”, which likely includes, for example, efforts to elevate young journalism professionals in order to better communicate with international youth audiences. While China’s propaganda apparatus has sought to make its content more accessible and appealing since at least 2009, the current era of propaganda work is marked by the increasing granularity with which content can be tailored based on audience data and modern communication technologies.

Analysis of Chinese academic articles shows that precise communication has been a research focus in China since the mid-2000s, but the vast majority of early (and many recent) articles relate to commercial advertising. Dr. Anne-Marie Brady, a professor at the University of Canterbury, has argued that China’s propaganda apparatus began borrowing theories from the advertising industry in the 1990s. Precise communication is almost certainly a theory absorbed from this field, with some writings acknowledging this advertising link. In both external propaganda and advertising, the implementation of precision-based strategies is intimately linked to the evolution of communication technologies. Chinese communication researchers believe that the current trends in communications, AI, and data processing technologies offer “advantageous conditions” for using the behavioral data generated online to reach target audiences (see the “Preparing the Keys” section for more on this topic).

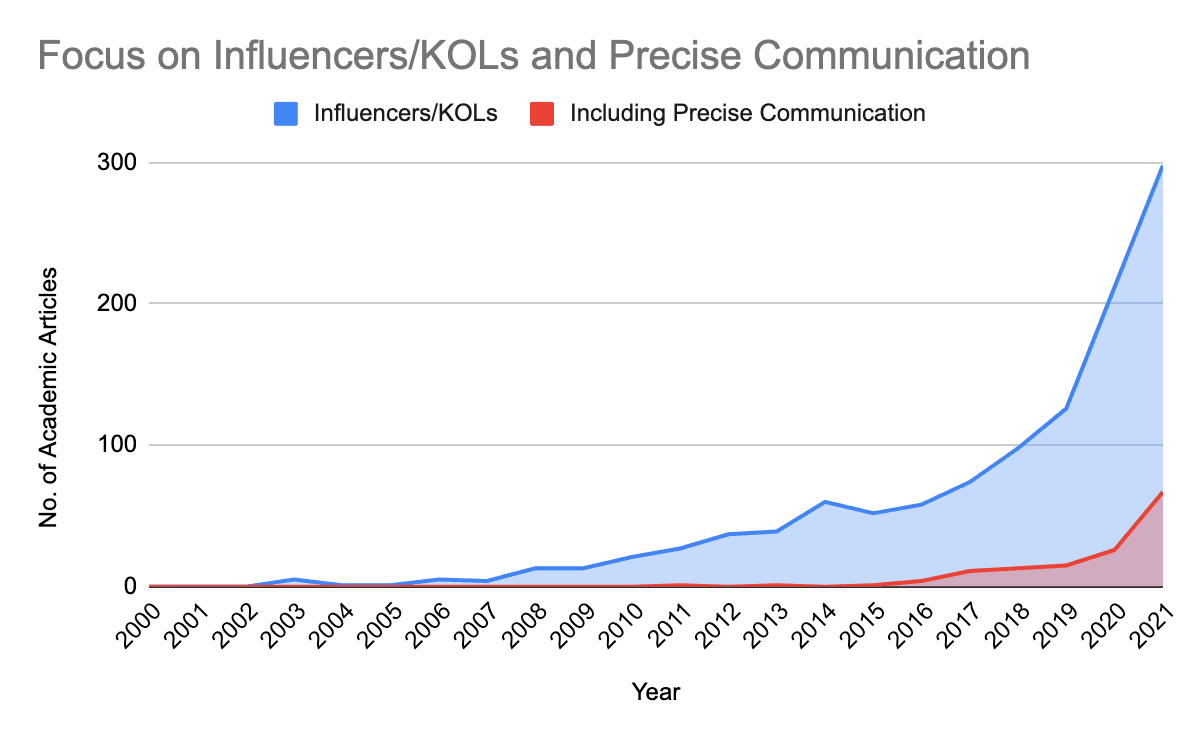

Precise communication for external propaganda work was being discussed as early as 2010, but it was not until 2015 that the number of articles annually published on this topic reached double digits (see Figure 1). Assuming an average 1-year lag between writing and publishing, this data points to 2014 as the year when research into precise communication for foreign propaganda started becoming mainstream. Figure 1 also indicates that the One Country, One Policy concept likely began emerging in 2016 (a year prior to the 2017 increase in publications). Research into the use of influential personalities — including internet influencers — emerged in the 2007-2008 period and has boomed since 2017. See the “Influencers and Newsletters” section for more discussion of this tactic in relation to precise communication.

Figure 1: Emergence of topics in external propaganda strategy research (see Appendix B for methodology); the Control line is all articles that reference “precise communication” in the title, abstract, or keywords, regardless of the topic (Source: Chinese academic database; compiled by Recorded Future)

Figure 1: Emergence of topics in external propaganda strategy research (see Appendix B for methodology); the Control line is all articles that reference “precise communication” in the title, abstract, or keywords, regardless of the topic (Source: Chinese academic database; compiled by Recorded Future)

These findings roughly correspond to some of the first authoritative indications of precise communication being implemented as part of the CCP’s overseas propaganda work, which occurred in the 2015-2016 period. For instance, People’s Daily Overseas Edition (人民日报海外版) highlighted its implementation of “audience differentiation” (分众化) in May 2015 and began experimenting with new forms of communication via WeChat the year prior. Dr. Mareike Ohlberg, a senior fellow with the German Marshall Fund, argues that “since 2015 CCP media have been pursuing a strategy of media localization . . . offering content in more languages and targeted at specific countries”. Although it appears not to have been explicitly linked to precise communication, China Global Television Network (CGTN; 中国国际电视台; 中国环球电视网) was also established at the end of 2016, rebranding CCTV’s overseas presence in a bid to aid the CCP’s “international public opinion discourse power”.

At a February 2016 CCP journalism and public opinion work symposium (新闻舆论工作座谈会), Xi Jinping personally elaborated, likely for the first time publicly, the core tenets of precise communication:

[We] must innovate [our] forms of external discourse and expression, research the habits and characteristics of different foreign audiences; adopt concepts, categories, and formulations that integrate the Chinese with the foreign; unite what we want to say with what foreign audiences want to hear; unite “emotion” (陈情) and “logic” (说理); [and] unite “I speak” with “others speak”; to make the international community and foreign audiences recognize (认同) [China’s] stories more.

Following Xi Jinping’s early 2016 instruction, the State Council Information Office (SCIO; 国务院新闻办公室) published a report discussing how China Daily (中国日报) was implementing the new strategy. It highlights how China Daily implements “reader audience differentiation” (读者分众化) and uses “audience differentiated [social media] accounts that target different regions [and] the demands of different readers with the goal of realizing precise communication”. That China Daily was able to point to its activities in prior years as evidence of this — such as the creation of its United States (US) Edition in 2009 — highlights how the CCP was striving to make its communications more receptive to foreign audiences even prior to 2015-2016. But as noted above, Chinese party-state media researchers believe the previous period was more focused on expanding China’s voice than the high-fidelity targeting that is now being pursued.

By no later than 2017, precise communication and One Country, One Policy were new pillars of the CCP’s external propaganda strategy and almost certainly widely understood as such. Hu Bangsheng (胡邦胜), the deputy head of China Radio International (CRI; 中国国际广播电台) in 2017, included One Country, One Policy in an article titled "How My Country's External Propaganda Realizes Precise Communication”. This was published in the CCP Central Party School’s (中共中央党校) journal, Chinese Cadres Tribune (中国党政干部论坛), with a version amplified by People’s Daily Online (人民网). At the 5th National External Communication Theory Seminar (第五届全国对外传播理论研讨会) hosted by the Communication University of China (CUC; 中国传媒大学) that year, then-deputy director of the SCIO Guo Weimin (郭卫民) argued that the “new chapter” of China’s external propaganda required audience differentiation, improved precision, and “‘One Country, One Policy’, ‘One Country, Many Policies’” (一国多策). Then-CUC dean Hu Zhengrong (胡正荣) presented a paper at the same seminar on One Country, One Policy and precise communication as “essentials” of effective international communication. Highlighting awareness of the new strategy, scholars at Tsinghua University identified precise communication as 1 of 4 main themes in a review of more than 1,200 academic articles from 2017 related to international communication.

Emphasizing, in addition to Xi Jinping’s 2021 remarks quoted above, that the precise communication almost certainly remains relevant to CCP authorities post-2017, the National Social Science Fund of China (NSSFC; 国家社会科学基金) funded research in September 2020 on “Precise Communication Strategy for the ‘Belt and Road’ Initiative on Overseas Social Media Platforms” (“一带一路”倡议在海外社交平台的精准传播策略). The NSSFC is administered by the National Planning Office of Philosophy and Social Sciences (NPOPSS; 全国哲学社会科学工作办公室), which is located within the CCP Central Propaganda Department. Propaganda and Thought Work in the New Era, which names precise communication as a “foundational principle”, was originally published in December 2020 and republished in March 2021. In June 2022, __China Daily__’s editor-in-chief further noted that “continually increasing the precision… of [China’s] international communication” is among the outlet’s forward-looking goals.

Theories of Target Selection

While the CCP’s policies regarding target selection are not known, communications researchers and media practitioners in China have provided a number of theories elaborating how external propaganda based on country-level distinctions and sub-country groups could work in practice. They tend to focus on: distinctions between ethnicity, culture, religion, and similar factors; overall bilateral relations between China and the target; and individual characteristics such as profession, gender, and hobbies. These are not authoritative descriptions of internal policy, but such research is likely similar to the kinds of discussions being had, and decisions being made, inside the CCP’s propaganda apparatus.

Among the earliest academic articulations of how propaganda targets could be grouped is a 2015 article by the same Hunan University scholars previously cited. They argue that international communication audiences should be grouped into 2 broad categories with sub-groups that determine the goal and content of China’s international communications, which are described below. Their ideas attracted the party’s attention: this article was first published in People’s Daily and republished by the SCIO and by the website of the CCP’s premier theoretical journal, Qiushi Online (求是网; QS Theory).

“Fundamental” (基本盘) Category: Strengthening communication with audiences in this category is critical to increasing China’s overall international communication power. The authors do not explicitly say why, but it is most likely because they believe audiences in this category will help establish a base of people who trust and share China’s communications. Audiences include: 1) Chinese people living overseas; 2) people in peripheral countries (regions); 3) people in “third-world countries”; 4) people in countries (regions) that are traditionally friendly to China; and 5) people in other countries with “relatively close economic, political, and cultural connections” with China.

“Key” (重点盘) Category: Communication with audiences in this category is important for strengthening China’s “right to speak”. The main audiences in this category are people in Western developed countries, namely in Europe and the US, as well as Western think tanks. This is because Western media enjoys a “monopoly of global communication resources” that countries in this category use to set global public opinion and because Western think tanks influence global governments.

The authors from Hunan University further argue that communication content should be sorted into “fundamental” and “key” categories also. The fundamental content category involves using finance, science and technology, education, culture, health, sports, and other topics to “disseminate information, delegate knowledge, [and] provide entertainment” (传播信息、传授知识、提供娱乐) because these issues have relatively little ideological color and will be more readily accepted by international audiences. The key content category involves “disseminating China’s voice, China’s proposals, [and] China’s positions [to] influence and guide public opinion and strengthen China’s right to speak”.

The most explicit, semi-authoritative statement on how targeting should occur under One Country, One Policy is found in the aforementioned 2017 article by then-deputy CRI head Hu Bangsheng. Hu discusses the need to understand the following characteristics of “every country”: historical culture, economic development level, social development phase, religious faith, customs and habits, and the personal interests of audiences. Within countries, Hu emphasizes the “situations” of different regions, different ethnicities, and different languages. Also writing in 2017, a scholar from East China Normal University’s School of Marxism (华东师范大学马克思主义学院) has advocated that the precise communication of China’s core socialist values can target propaganda based on an analysis of the value orientation and interests of political groups (such as level of government, public work units, and civil-social organizations) and occupational fields (such as agriculture, industry, commercial sector, and services). While this scholar is largely concerned with domestic propaganda work, they explicitly see China’s core socialist values as a cultural export and assert that the target audience should include Chinese people in Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, and other jurisdictions.

While China’s communications infrastructure is now global in scope, some Chinese researchers argue that external communications should more narrowly focus on countries, and their audiences, where influence will best serve China’s political, economic, and cultural interests. From this perspective, other researchers from Hunan University suggest classifying target countries according to an “inverted pin” (倒品字) model. In this model, target countries would be selected based on the relationship between their distance from China in terms of geography, culture, psychology, and language; the international influence they possess; and China’s interests.

Other researchers have proposed a more comprehensive and forward-looking model for how China should achieve precise communication based on stratification (分层), classification (分类), and grouping (分群), as defined below. This model was put forward in 2021 by Hu Zhengrong, former CUC dean and the current head of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences’ Journalism and Communication Research Institute (中国社会科学院新闻与传播研究所), and a media practitioner affiliated with China Media Group’s (CMG; 中央广播电视总台) Hong Kong-Macau-Taiwan Programs Center (港澳台节目中心). Hu and his co-author argue that stratified communication, classified communication, and group communication are a principle (原则), a strategy (策略), and a method (方法), respectively. Although the authors do not explicitly call this a “model”, when viewed together, the 3 features can be understood as an outline for a potential future “Chinese discourse and Chinese narrative system of systems” (中国话语和中国叙事体系) that involves participation from government, media, companies, and think tanks.

Appendix A presents a diagram of the model proposed by Hu and his co-author with their examples of specific targets and suggestions for how to differentiate content based on target audience characteristics. The core components of the model are summarized below:

Stratification: This means differentiating among various social classes, such as political elites and the masses, and communicating with these classes in different manners, with different content.

Classification: This means A) differentiating the roles that various entities within China play in international communication and B) differentiating discourse targets, first regionally, then gradually by country.

Grouping: This means targeting content and choosing communication channels to be maximally effective for granular segments of a given social class, country, or region based on factors like the target audience’s gender, religion, interests, and hobbies.

Interestingly, Hu and his co-author assert that One Country, One Policy has fallen short of its goals due to limited human capital, funding, and dissemination channels (渠道手段). They state that implementing One Country, One Policy in the short term is still “very challenging” from the perspective of 2021, and that “completely realizing [the goal of] closely sticking to different countries and adopting different communication methods is not realistic” at this time. Achieving this is still the ultimate goal, but it first requires improvements to China’s overall discourse system. This is why they argue that China should first differentiate (classify) based on regions or blocs of countries and gradually work toward achieving One Country, One Policy.

Actors: The Right Voice for the Message

While official party-state media outlets are almost certainly among the leading implementers of precise communication efforts given their public opinion guidance mission, others are also very likely involved. As discussed below, precise communication is most likely converging with other external propaganda strategies that focus on finding the right communicator for achieving influence among a target audience.

Authoritative sources such as Propaganda and Thought Work in the New Era do not explicitly identify what entities are responsible for carrying out this strategy. Given precise communication’s status as a “foundational principle” for external propaganda, it is likely meant to be implemented or facilitated by a wide range of entities that contribute to China’s international communications. The entities and types of entities named in academic writing on precise communication, news reports about One Country, One Policy in practice, and the discussion in Propaganda and Thought Work in the New Era regarding how the CCP’s external propaganda is implemented broadly include, but are not limited to:

- CCP Central Propaganda Department

- State Council Information Office

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA; 外交部)

- Propaganda departments (宣传部门)

- Local government departments

- “Mainstream media” (主流媒体)

- State-owned and private enterprises

- Chinese think tanks

While the focus of precise communication is on finding out what to say to the right audience and how to say it for maximum effect, some researchers also assert that China must select the right communicator for disseminating information to the target. The model put forward by Hu Zhengrong and his co-author includes such an argument, for example (see Appendix A). Although not always linked to precise communication explicitly, this idea is often seen alongside it in writings that discuss the trajectory of the CCP’s strategy. As noted in the “CCP External Propaganda Work” background section, since at least 2004, the CCP has sought to coordinate the dissemination of its narratives and preferred image of China internationally through a variety of entities that form a “chorus” of voices and “tell China’s story well on every battlefront”.

The following sections, “Preparing the Keys” and “Opening the Locks”, also discuss how social media and marketing companies in China and abroad aid China’s propaganda apparatus by providing behavioral data, audience surveys, advertising tools, and other support. Additionally, while beyond the scope of this report, it is noteworthy that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA; 中国人民解放军) is very likely exploring and implementing precise communication as part of its own influence operations.

Preparing the Keys: Understanding the Audience

Tailoring content according to the beliefs and interests of target audiences, party-state media and other elements of the propaganda apparatus requires as strong an understanding as possible of those audiences. Propaganda and Thought Work in the New Era, CCP leaders, party-state media practitioners, and academics all agree on this point. Country studies research, in-country surveys, and online behavioral data are the means of attaining this understanding; indeed, the internet and social media are what make increasingly granular forms of precise communication possible in both political and marketing contexts. As implementation of precise communication deepens, such data will almost certainly increasingly shape the CCP’s external propaganda output — the “keys” that will “unlock” different international audiences.

After Xi Jinping’s 2016 remarks emphasizing “research [into] the habits and characteristics of different foreign audiences”, Hu Bangsheng stressed the necessity of conducting “empirical research on different countries, regional research, and audience research” in 2017. A researcher affiliated with the Wenzhou University Public Opinion and Online Information Security Research Center (温州大学舆情与网络信息安全研究中心) likewise asserted in 2018 that implementing One Country, One Policy necessitates “fully surveying, researching, and analyzing the political background, legal system, ethnic religion, customs, and cultural traditions, [and other elements] of the audiences of different countries . . . [and] making external [communicators] become specialized talent that ‘knows some country’ or ‘knows some aspect of some country’”. The director of the National Discourse Research Center (国家话语研究中心) at Suzhou University of Science and Technology (苏州科技大学) has further highlighted the requirement of “strengthening regional and country theoretical studies . . . on-the-ground survey research… [and achieving] a basic understanding of a specific audience group’s interests, hobbies, needs, and values”.

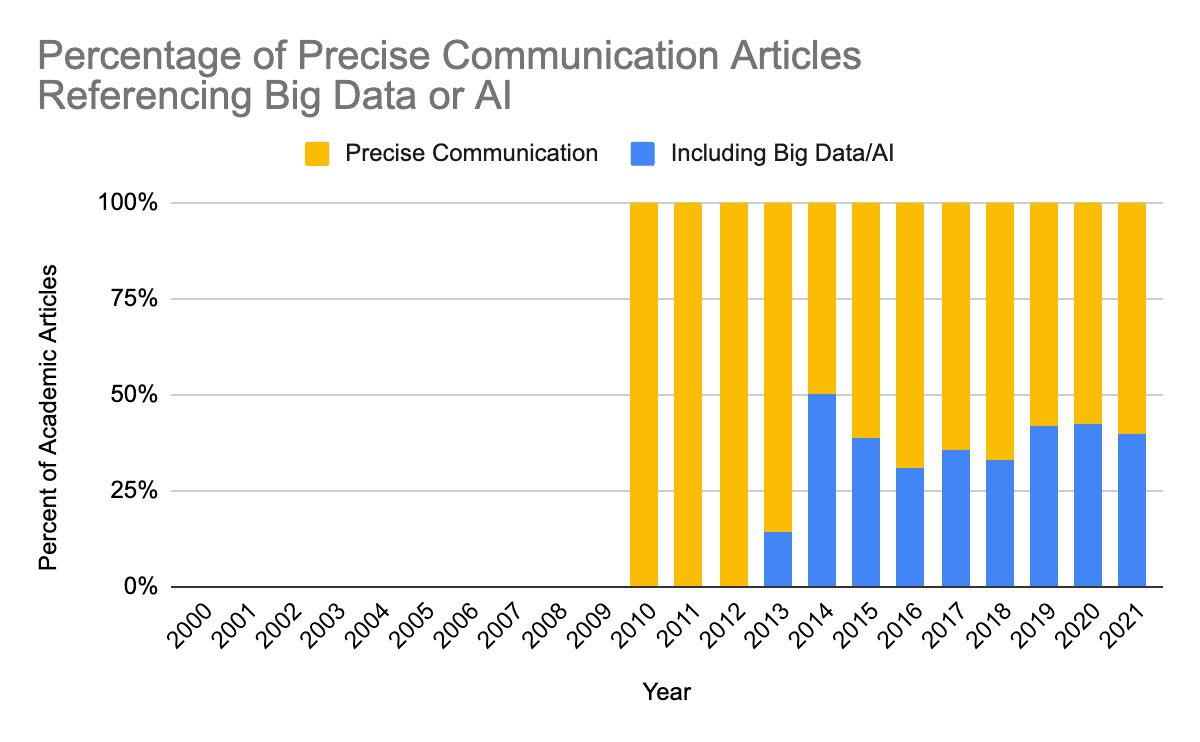

A topic of discussion for a third or more of precise communication research articles since 2015 is the role of big data and AI (see Figure 2). Multiple researchers, including the director of __Xinhua__’s Journalism Research Institute, have argued that “user portraits” (用户画像) created on the basis of “interest tags” (兴趣标签) and other personal information and online behavioral data are a requirement for implementing precise communication. As early as 2014, the then-executive deputy director (常务副主任) of the Global Times Public Opinion Survey Center (环球舆情调查中心), a subsidiary of Global Times (环球时报), suggested that such data could be used to identify audience preferences, the appropriate voice, and the best time for disseminating information as part of determining not just “what to say” (说什么) but also “how to say it” (怎么说) for maximum effect. Writing about domestic propaganda in 2017, the then-editor-in-chief (总编辑) of People’s Daily Online and president of the People’s Daily Online Research Institute (人民网研究院) went further, suggesting that precise communication should also be informed by combining an individual’s behavioral data with data about their physical setting (场景).

Figure 2: Percentage of precise communication articles that reference big data or AI; see Appendix B for methodology (Source: Chinese academic database; compiled by Recorded Future)

Figure 2: Percentage of precise communication articles that reference big data or AI; see Appendix B for methodology (Source: Chinese academic database; compiled by Recorded Future)

In a co-authored 2021 article, the director of, and a public opinion analyst (舆情分析师) from, China Daily’s International Communication Research Office (中国日报社国际传播研究室) acknowledge the need for surveys and behavioral data. They stress that Chinese media needs to use “internet technology” and “big data technology” to continue improving its ability to produce information according to international opinion and based on the kind of reporting that has worked in the past. This effort, the authors write, demands “strengthening overseas audience research”, which can be facilitated by “new media methods” (that is, data collection) and “cooperation with international third-party survey consulting companies”; more closely studying how readers interact with published media items (also pointing to behavioral data); and creating a “3-in-1 ‘public opinion-audience-effect’ monitoring system”. Writing in June 2022, the editor-in-chief of China Daily asserted that the outlet’s international communications research departments are focused on “using big data, artificial intelligence, and other methods to achieve precision-ization [精准化]” as part of establishing a “good foundation for enhancing [China’s] ability to set the agenda“. Notably, the focus on bulk data is not limited to discussion of precise communication but relates to broader thinking on how AI and data can empower the propaganda apparatus to more effectively preempt and mitigate threats.

Country and Audience Surveys

A major contributor to China’s survey efforts is the Academy of Contemporary China and World Studies (ACCWS; 当代中国与世界研究院), a think tank subordinate to the China Foreign Languages Publishing Administration (CFLPA; 中国外文出版发行事业局), which is itself a work unit of the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department. Since 2013, ACCWS has produced the annual China National Image Global Survey Report (中国国家形象全球调查报告). International market research firms, namely Millward Brown, Lightspeed Research, and Kantar Group (which owns the first 2 firms), have conducted the surveys for all of these publications. These and other surveys create data that Chinese media and the propaganda apparatus use to demonstrate China’s achievements under the CCP’s leadership, as well as data that almost certainly informs communication strategy and international communication planning.

ACCWS’s surveys evaluate current perceptions of China in different parts of the world and ask, since 2014, forward-looking questions about what different groups want to see. They ask respondents which China-related topics they are most interested in, with response options including politics, military, sports, culture, and other categories. They also ask respondents in which areas they would like to see China play a larger role in global governance, with response options including economics, security, ecology, and other areas. Responses to these and similar questions are typically broken out into developed versus developing countries and 3 different age groups for the public report. Although ACCWS’s reports do not dwell on country differences or differences between respondents of different age groups in various countries, it is clear that the surveys generate such data.

ACCWS also conducts other, more focused survey research to understand perceptions of China. For example, ACCWS presented results from its study titled “China and the World in the Eyes of International Youth” (国际青年眼中的中国与世界) in October 2021. Since at least 2014, ACCWS, in partnership with 1 or more of the foreign firms named above and other entities in China, has produced a series of reports on international views toward Chinese enterprises. The 2020 edition of these reports focused on 12 countries participating in the Belt and Road Initiative.

Party-state media outlets further fund their own survey research to improve foreign-facing products. For example, China Xinhua News Network Corporation (CNC; 中国新华新闻电视网有限公司) sought to evaluate its international communication in October 2017. According to procurement records, the contract winner agreed to conduct surveys in New York, London, and “major countries and cities in Africa” to help CNC understand its overall effect internationally; understand the effects of its “major international partnered communications”, overseas distribution centers, documentaries, and other projects; and learn how to increase its competitiveness by retaining current audiences and attracting new viewers. The project was sole-sourced to CTR Market Research (央视市场研究股份有限公司), a joint venture between China International Television Corporation (国国际电视总公司) and Kantar Group.

In June 2021, CMG similarly solicited bids for conducting surveys to understand the reach and impact of their worldwide TV, broadcast, website, and social media presence. According to the tender announcement, CMG budgeted 7.5 million RMB (approximately 1.2 million USD) for this project and sought to collect data from no less than 500 people in each of 52 countries and 41 languages. The surveys were required to evaluate the visibility, contact, spread, trust, satisfaction, favorability, authority, market competitiveness, and comprehensive communication power of CMG’s various dissemination channels. They were further intended to address the overall efficacy of CMG’s content in all languages within a single country, as well as the overall efficacy of CMG’s content across all countries speaking a given language. The final deliverable was also required to include summaries of the culture and media environment (such as which short-form and long-form video platforms are popular) of all countries surveyed. Global Times 4-D Market Survey, also known as the Global Times Public Opinion Survey Center, won a modified version of this tender.

Party-state media and other entities are also leading the creation of new research entities to explore target audience attitudes in more depth. For example, China Daily established a Generation Z Research Center (Z世代研究中心) in 2022 with “the Department of Sociology of Peking University, the School of Journalism of Fudan University in Shanghai, the School of International Journalism and Communication at Beijing Foreign Studies University, the Institute of Sociology at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the Bilibili Institute for Public Policy and the Beijing Shengtao Institute of Educational Development and Innovation”. The results of a 2022 Global Generation Z Insights Report, “based on questionnaires and in-depth interviews with 3,000 young people in 50 countries and regions, including China, France, Egypt, South Korea, the United Kingdom and the US”, were released at the inaugural ceremony of this new think tank. Earlier, in 2021, China Daily reportedly signed a cooperation agreement with the External Propaganda Office of Shanghai (上海市委外宣办) to establish a think tank aimed at “innovation for ‘Generation Z’ international communication theory and practice”.

Behavioral Data Collection

Public opinion monitoring is an industry unto itself in China, write Jessica Batke, ChinaFile senior editor, and Dr. Ohlberg. In addition to serving commercial and security purposes, this industry supports the work of party-state media in China and abroad. The companies and research centers that offer international public opinion monitoring and related online marketing services provide a basis for conducting precision communication. Demonstrating that the link between such services and information influence is recognized in China, an associate senior public opinion analyst (主任舆情分析师) at the People’s Daily Online Public Opinion Data Center (人民网舆情数据中心) has pointed to the 2016 US election influence scandal involving Cambridge Analytica — whose core service is “better audience targeting” — and Facebook in discussing the “guidance and intervention” phase of public opinion research. During the 2020 US presidential election, the People’s Daily Online Public Opinion Data Center reportedly “carried out collection of all content issued by the personal . . . accounts of Joe Biden and Donald Trump” on a popular American social media platform. The center further conducted analyses to “compare differences in the political persons, key opinion leaders [KOL; 关键意见领袖], and media that often engaged” with Biden and Trump.

China Daily likewise seeks to harness foreign online data through commercial industry to understand the effects of its reporting, guide topic selection, and be forewarned of sensitive events. For instance, China Daily is a “partner” (合作伙伴) of China Data Matrix Technology (Beijing) Limited (中数经纬科技(北京)有限公司), and the China Daily (Hong Kong) Big Data Center (中国日报(香港)大数据中心 specifically is almost certainly a client of this company. China Data Matrix is a media monitoring company that claims to have “complete coverage” of Facebook, Pinterest, Instagram, Linkedin, YouTube, Line, and other major platforms, web portals, communities, forums, and blogs from over 100 countries and 10 languages. Their products support “coverage and dynamic updating of foreign social media KOL in every country, [with] precise and real-time directed collection and monitoring”, and are capable of generating user portraits.

Xinhua News Agency has a subsidiary known as Beijing Xinhua Multimedia Data (北京新华多媒体数据有限公司), or Xinhua Data (新华大数据) for short, which operates a Public Opinion Monitoring Platform (“新华大数据”舆情监测平台) that collects data from 4,500 foreign websites, including some in Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. Xinhua Data’s “partners” include Xinhua News Agency, Xinhuanet (新华网), People’s Daily Online, and CCTV. On a single popular American social media platform, Xinhua’s platform covers 6 million accounts, “supporting search and collection on more than 2,000 key words”. This is less than 3% of the platform’s overall user base, suggesting Xinhua is likely selectively targeting accounts (or types of accounts) of interest. Procurement documents analyzed by __The Washington Post__’s Cate Cadell likewise show that party-state media and others have sought programs that monitor prominent foreign journalists, academics, and “key personnel from political, business and media circles”. Other companies appear to cast a much wider net; Global Tone Communications Technology (中译语通科技股份有限公司), a company indirectly subordinate to the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department, “facilitates bulk data collection . . . from traditional and social media”. The company “claims that one of its . . . [media monitoring] platforms . . . collects 10 terabytes of data per day, and about 2–3 petabytes per year”.

In some cases, there appears to be a discrepancy between the marketing of companies and research centers in the public opinion monitoring industry and their actual capabilities. Beijing TRS Information Technology (北京拓尔思信息技术股份有限公司), whose clients include People’s Daily, Xinhua, and other major outlets, offers a platform that claims to collect from foreign sources. However, the company’s sample products demonstrating collection capability during the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests in the US indicate that “62.16 percent of more than 23.5 million messages and articles analyzed . . . were pulled from Weibo or WeChat. In contrast, just 3.43 percent of the messages analyzed came from non-Chinese media sources”.

Still, it is clear that the party-state is intent on pursuing research into technologies and data processing techniques that will facilitate improvements to AI’s application in targeted external propaganda work. The International Communication Big Data Intelligent Laboratory (国际传播大数据智能实验室), for instance, is a research entity dedicated to this pursuit. This laboratory was jointly established in April 2019 by the CFLPA and Renmin University of China (中国人民大学), specifically the Gaoling School of Artificial Intelligence. In September 2021, the laboratory began soliciting bids for research on: “Model Construction and Strategy of International Communication Big Data Region and Country Profiles”; “Intelligent Profile Modeling for International Communication with Youth Groups on the Mobile Internet”; and “Big Data Evaluation Model for the Influence of International Social Media Opinion Leaders”.

Opening the Locks: Delivering Tailored Content

The adoption of a precise communication-based strategy is moving the CCP’s entire propaganda apparatus toward the creation and dissemination of media products that are tailored to, and intended to be enjoyable for, specific segments of audiences. To do this, the CCP is relying on media localization, joint content production partnerships, distribution contracting, and almost certainly advertising tools from international internet companies. Xi Jinping asserted in 2015 that “wherever audiences are . . . that is where the focus of propaganda and thought work is and [where its] foothold must be placed”. Considered alongside the tenets of the precise communication strategy defined above, this means finding groups who, from the party’s perspective, need to be influenced and giving them bespoke products embedded with the CCP’s messages — that is, using targeted propaganda to turn these “locks”.

Media Localization

Discussing both precise communication and One Country, One Policy, Propaganda and Thought Work in the New Era calls on CCP cadres to “deepen implementation of the [media] localization strategy. . . . connect [接] to local ‘flavor’ [本土“地气”], assemble local ‘personalities’ [当地“人气”] . . . [and] encourage the creation of overseas localized production centers, dissemination centers, [and] promotion centers”, among other actions. A form of deeper localization beginning in 2015 is seen in the relationship between the American media conglomerate Discovery and the China Intercontinental Communication Center (CICC; 五洲传播中心). These entities have collaborated since at least 2004 to create China-related TV programming, and strengthened their partnership in 2015 when they signed a 3-year agreement to launch “a dedicated programming block” called “Hour China”. This block was aired “weekly on Discovery Channel across [the] Asia-Pacific, reaching more than 90 million viewers in 37 countries and territories”, and was reportedly “the first time that an international media company . . . launched a . . . programming block of this scale dedicated solely to China”. That same year, “Xinhua and the China Daily newspaper started using automatic geolocation to redirect [users] to a specific language version of their page on Facebook”.

In late 2021, Discovery’s Southeast Asia Channel and some regional versions of the online platforms Discovery+ and Amazon Prime Video began airing Journey of the Warriors, a joint production between Discovery, Tencent Video (腾讯视频), and CICC. Research on this show by China Media Project finds that the “‘adventure documentary’”, which follows 5 celebrities as they retrace the Long March, has been recognized in China as an example of “‘Turning External Propaganda Documentaries into Blockbusters for the World to See’” and of “‘perfectly integrating stories of revolutionary history with the international communication discourse system in a way that foreigners find easy to understand and accept’”. China Media Project also found the show “truly entertaining” at times, noting that this has historically been a rare achievement for China’s external propaganda products.

Distribution agreements with foreign media are another form of localization. An example of this tactic is seen in __China Daily__’s “China Watch” (中国观察报) content, which in 2021 was “designed according to the situations of different countries, different languages, and different audiences” and inserted into 30 foreign media outlets in 23 countries. Also in 2021, China Daily disseminated 17,000 articles in various languages to more than 200 “foreign mainstream media web portals and platforms”, a 143% increase from the previous year.

At least some distribution agreements include explicit requirements related to precise communication. In 2019, the government of Hainan and Russia’s state-owned news agency TASS signed a cooperation agreement. Procurement records from December 2021 related to this 5-year agreement state that it is intended to “strengthen communication of Sanya’s policies, opportunities, and achievements in Belt and Road Initiative countries . . . by sticking closely to the precise communication methods of [differentiating between] different areas, different countries, and different groups”. A contract issued to the Hainan-based media company that manages the relationship with TASS — Hainan Hesi Zhongmei Cultural Media Company (海南合思众美文化传媒有限责任公司) — stipulates that coverage of Hainan should be distributed, presumably by TASS, via:

- Other Russian news outlets and those in Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Azerbaijan

- Social media, including Facebook, YouTube, and Russian social media platforms VKontakte (VK) and Odnoklassniki (OK)

- Russian-speaking key opinion leaders (KOLs)

Furthermore, distribution platforms and target audiences should be prioritized based on age, profession, income, education level, industry, and interests. The overall goal of the contract is to attract "famous international firms" and "exceptional talent" to Hainan, as well as target Generation-Z audiences.

Global internet companies offer a similar opportunity to that seen in the TASS contract, whereby precise communication goals are furthered by providing access to audience data that party-state media would otherwise be challenged to obtain. In case studies for the ChinaTalk newsletter, Maggie Baughman has highlighted, based on procurement records, how Chinese government entities are almost certainly benefiting from Facebook’s advertising tools. At least 2 government tourism departments have contracts with Beijing Yiqilian Technology Company (北京亿起联科技有限公司), whose platform “PandaMobo” (熊猫新媒) is an “official partner” (官方合作伙伴) of Google, TikTok, Facebook, and other prominent platforms. On Facebook, and presumably with the help of its audience analytics, Beijing Yiqilian runs a “Visit Xiamen” page and distributes other content that contributes to perceptions of China. These tools include data on user age, gender, interests, behavior, and “precise” location. Although the focus of the Hainan-TASS and Yiqilian’s local government contracts described here is not overtly political, economy and tourism are part of CCP external propaganda work and contribute to China’s overall international image. Moreover, these pathways are almost certainly the same as those that overt political narratives will flow through.

Social Media Differentiation

How China’s diplomats and party-state media use foreign social media accounts is also very likely informed by the tenets of precise communication. At the inaugural China Internet Civilization Conference (中国网络文明大会) in 2021, MFA spokesperson Zhao Lijian (赵立坚) asserted that “we” — presumably meaning China writ large, which includes the diplomatic corps — “use language that Western audiences understand, methods that [make them] listen [听得进], [and] content that [they will] believe to make China’s narrative become the world narrative and international consensus”.

As of March 1, 2021, there were at least 270 Chinese diplomats stationed in 126 countries that had accounts on major international social media platforms. Most diplomatic accounts, including those for embassies and consulates, were created in or after 2015, with a surge in 2019 (see Figure 4). Their communications, especially those with more personalized accounts, have been analyzed in the context of precise communication by Chinese researchers. For example, scholars from the Arab Studies Institute at Beijing Foreign Studies University (北京外国语大学阿拉伯学院) argue that China’s ambassador to Saudi Arabia, Chen Weiqing (陈伟庆), addresses the “information and cultural psychological needs” of his audience, attends to the “issue of ‘what does the audience want to understand’ and ‘what do we want the audience to understand’”, and achieves “precise communication”. Chen, the authors assert, presents himself as an “old friend”, lively, kind, modest, and cultured, instead of as a “serious and cautious diplomat in the traditional sense”, thereby increasing the “affinity” of his messages among the target audience. They find that 97% of Chen’s posts are in Arabic, and that Chen focuses on cultural topics (such as calligraphy) and social issues (such as youth employment) while expressing respect for and interest in Saudi Arabian culture and development. The latter emphasis, the scholars assert, is in contrast to the criticism that Saudi Arabia receives from the West.

A 2022 analysis by BBC Monitoring and CASM Technology of 691 international social media accounts used by China’s ambassadors, consular officials, the MFA, and Confucius Institutes found variations in the content pushed toward different regions (see Figure 3). For instance, “Africa, the Asia Pacific and the Americas saw a greater emphasis on Covid”, while “Europe and the Americas saw much greater emphasis on culture” and “the Middle East saw a greater emphasis on politics”.

Editor’s Note: The following post is an excerpt of a full report. To read the entire analysis, click here to download the report as a PDF.

Related